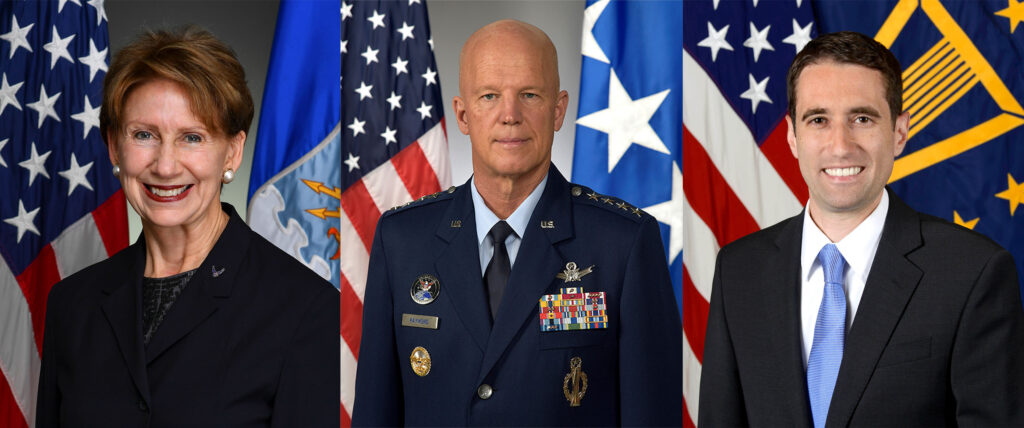

Barbara Barrett (left), Gen. Jay Raymond (center) and Steve Kitay (right)

CORRECTION: DoD SAYS IT “COORDINATED” WITH NRO, DEFENSE INTEL AGENCIES; ODNI “INFORMALLY COORDINATED” ON DSS.

WASHINGTON: In contrast to President Donald Trump’s often inflammatory rhetoric disparaging allied leaders and rejecting international cooperation, the Pentagon’s new Defense Space Strategy (DSS) prioritizes cooperation with allies and partners.

“We are not alone in our endeavors,” Steve Kitay, deputy assistant secretary of defense for space policy told reporters today. “Our space-capable allies and partners, as well as the growing and innovative space industry, offer tremendous opportunities for space cooperation.”

This includes, sources say, opening up the classified annexes to two more allies in addition to the traditional Five Eyes partners (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and U.S.). While sources didn’t reveal the countries added, they are probably France and Germany, which both in February joined the 2014 established Combined Space Operations (CSpO) Initiative (not to be confused with the Combined Space Operations Center, or CSpOC).

“It’s a big disconnect,” said one long-time space policy player of the DoD language vice Trump’s overarching approach. “(Former Defense Secretary Jim) Mattis quit over basically that point.” Noting that the National Defense Strategy enshrines cooperation with allies and partners as well, the official said “DoD ain’t gonna abandon that just because of Trump’s unilateralist rhetoric and ‘America First national strategy for space.”

(The most recent example of Trump’s dim view of alliances is that he has confirmed the US will pull 25,000 troops from Germany due to the contention that the government of Angela Merkel spends too little on defense. Germany has refused to meet a NATO pledge it took to spend at least 2 percent of GNP by 2024. Its defense minister, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, promised last year to hit that level by 2031.)

While the strategy commits to closer coordination with allies on both policy and military operations, there seems to have been little, or no, coordination with other US government agencies in crafting the DSS. This includes, we hear, between the military and the Intelligence Community.

One source with a pedigree in the Intelligence Community told Breaking D there was no coordination with any part of the IC, not even the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). “This is a just a DoD product. The 2011 National Security Space Strategy was very much a DoD-IC product,” our source said.

CORRECTION BEGINS. Kitay, however, told Breaking D today that this assertion is flat wrong.

“The Defense Space Strategy was developed to provide guidance to the Defense Department, building on the President’s National Strategy for Space and the National Defense Strategy. It was thoroughly coordinated with the Defense Intelligence Enterprise, to include defense agencies such as the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), as well as informally coordinated with key interagency stakeholders such as the Office of the Director for National Intelligence.” (The Defense Intelligence Enterprise means NRO and other agencies which report to DoD, including the Defense Intelligence Agency.)

A DoD official further stressed that the NRO Director, Christopher Scolese, signed off on the DSS; although explained that the document itself is focused on the DoD, not a joint product with the IC or any other agencies.

An NRO spokesperson told Breaking D in an email statement today: “Throughout the standup of the U.S. Space Command and the U.S. Space Force, the NRO has worked closely with our IC and DoD partners to align efforts with national space policy and direction – ensuring that NRO capabilities and operations continue to support both national decision makers and warfighters in all domains. With regards to the new Defense Space Strategy released yesterday, the NRO did coordinate on the review and remains actively engaged with our partners in shaping the next generation of joint, multi-domain space strategy and operations.”

(The DSS definitely was not coordinated with the civil agencies, according to both DoD and other USG sources, even though it implicates at a minimum both the Departments of State and Commerce. Those agencies, a DoD source said, will be roped in as the DSS is being implemented.)

As far as we can tell, part of the problem of sussing out what happened revolves around the meaning of the word “coordinate.” (To quote from the beloved film “The Princess Bride:” ‘I do not think that word means what you think it means.’)

Coordination can mean a senior official was asked to weigh in as drafting goes along to ensure there are no conflicts and that his/her agency is correctly vested; or it can mean that he/she is simply asked to sign off on the final draft. It can also mean a committee-like drafting process involving multiple experts from agencies implicated in the issues at hand, so the end-product can be a truly joint one. And “informal coordination” seems to refer to a review of the nearly final version to give agency reps a heads up; although it is unclear what would happen if the reviewing agency shouted ‘stop the presses.”

The drafting of the 2011 NSSS, sources say, involved many, many meetings including staff experts from across the IC. It appears that the DSS did not go through a similar drafting process.

That said, according to a former USG official involved in the 2011 process, the reason the IC signed off on the NSSS was because it said nothing that affected their equities, just as the DSS does not affect IC equities. “It is like me telling you that I ordered a pizza for myself — I’m not ordering for you — and asking you if that’s OK. Of course you are going to say OK, you don’t care,” the source said. CORRECTION ENDS.

This raises questions about where the military strategy stands in the hierarchy of top-level policy guidance on space, as well as about how well DoD is coordinating with the IC overall in the wake of the creation of Space Force and Space Command. As Breaking D readers know, the issue of NRO’s future role is already in the wind as a result of those changes.

UPDATE BEGINS. A DoD official today explained the relationships among the documents as such: The 2011 NSSS signed by President Barack Obama, and involving the entire IC and DoD, is “OBE,” following Trump’s 2018 National Strategy on Space. The NSS in addition to DoD and the IC guides civilian agencies with space-related missions such as NASA. So, like the National Security Strategy begets the National Defense Strategy, the NSS begets the DSS. (We confess we are still a wee bit confused.) UPDATE ENDS.

Further, a number of insiders pointed out, the National Security Council is planning to release a new National Space Policy in September — which begs the question of why DoD didn’t wait to ensure that the DSS was aligned with that document.

UPDATE BEGINS. The former USG official noted that the timing of the DSS seems inexplicable, given that the new National Space Policy is already in draft form and that DoD is aware of the timeline because it is involved in the process. “It’s entirely possible that the new DSS could be made OBE by the new space policy,” the official said. UPDATE ENDS.

The new strategy is based on what fixing DoD calls the “central problem” that “the U.S. defense space enterprise was not built for the current strategic environment. The intentions and advancements of potential adversaries in space are threatening the ability of the United States to deter aggression, to protect U.S. national interests, and to fight and win future conflicts.”

While Kitay insisted that the US is still ahead of Russia and China in space, he stressed that US adversaries are catching up fast, and that Russian and Chinese capabilities present “very real threats.”

Accordingly, the DSS has three objectives:

- “Maintain Space Superiority: DoD will establish, maintain, and preserve U.S. freedom of operations in the space domain. DoD will be prepared to protect and defend U.S. and, as directed, allied, partner, and commercial space capabilities and to deter and defeat adversary hostile use of space.

- Provide Space Support to National, Joint, and Combined Operations: DoD space forces will deliver advanced space capabilities and effects to enable national, joint, and combined operations in any domain through sustained, comprehensive space military advantages. DoD will leverage and bolster a thriving domestic civil and commercial space industry.

- Ensure Space Stability: In cooperation with allies and partners, DoD will maintain persistent presence in space in order to: deter aggression in space; provide for safe transit in, to, and through space; uphold internationally accepted standards of responsible behavior as a good steward of space; and support U.S. leadership in space traffic management and the long-term sustainability of outer space activities.”

The emphasis on “space superiority” harkens back to the controversial 2006 National Space Policy of President George W. Bush. That phrase was subsequently banned by the Obama administration in its space policy and strategy documents because of its aggressive overtones.

“Big picture, it’s definitely heading back toward Bush v. Obama, both in tone and substance,” the space policy expert said, albeit with several exceptions.

One exception is that the DSS’s explicitly pledges to “deter” aggression against the commercial satellite industry. This begs the question of whether DoD is now proclaiming a new more active role in protecting commercial space assets, as part of the Trump administration’s campaign of economic and political support for the US space industry — including its ambitions to expand its reach beyond near-Earth orbit to activities such as asteroid mining and lunar resource extraction.

Indeed, Victoria Samson, Washington office director for Secure World Foundation, posted on Twitter that she reads the DSS language on “provide for safe transit in, to, and through space” as “covering Earth orbits AND cislunar ones too.”

As Breaking D readers know, national security space leaders have been consumed by concerns that adversaries, especially China, are seeking to push military space operations into the cislunar region. In general, the term “cislunar” refers to the region between Geosynchronous Orbit — 36,000 kilometers above the Earth — and the Moon. Some definitions include orbits slightly beyond the Moon as well.

Gen. John Thompson, head of Space and Missile Systems Center, told the Mitchell Institute this morning that China has undertaken “numerous lunar activities that have caused some of us some concerns.”

The DSS further lays out four so-called “lines of efforts” to achieving the strategy:

- Build a comprehensive military advantage in space. This includes developing counterspace capabilities, ensuring space superiority, and developing a new doctrine and culture focused on warfighting. It also includes improving “intelligence and command and control (C2) capabilities that enable military advantage in the space domain.”

- Integrate military spacepower into national, joint, and combined operations. This reflects DoD’s high priority effort to flesh out its concept for a new way of war: all domain operations. “The integration of superior space capabilities into and throughout the Joint Force, along with operational integration with allies and partners, is essential for securing our military advantage against threats in space,” the strategy says.

- Shape the strategic environment. This includes working with allies and the State Department to “coordinate space messaging” and “promote standards and norms of behavior in space favorable to U.S., allied, and partner interests.” It also includes informing the public about space threats.

- Cooperate with allies, partners, industry, and other U.S. Government departments and agencies. Interestingly, the DSS language hints that DoD might allow allies to provide capabilities that the US is not as focused on or cannot afford on its own, using the term “burden sharing” — which old policy hands know comes with a great deal of baggage in NATO circles. The DSS says: “DoD will promote burden-sharing with our allies and partners, developing and leveraging cooperative opportunities in policy, strategy, capabilities, and operational realm.”

Kitay asserted that the DSS provided the classic elements of a good strategy — an articulation of the “ends,” supported by the “ways” to achieve it, and lastly the “means” or resources to do so. However, a number of space policy experts complained to Breaking D that the document is extremely vague, especially regarding “means” for achieving its ambitious “ends.” In other words, as the old saying goes, it’s ‘all hat and no cattle.’

“I’m less than impressed. In my opinion, it’s actually a step backwards from the 2011 strategy because it has even fewer details on exactly how they’re going to achieve the lofty goals they set forth,” said Brian Weeden, program director at the Secure World Foundation. “Good strategy is connecting ways, ends, and means. This document is big on the ends, vague on the ways, and says nothing about the means.”

UPDATE BEGINS. DoD, however, points out that what was released yesterday is not the full picture. “Most strategies that the Department does are classified documents, and we do an unclassified summary of them. What went out to the public is an unclassified summary that does not contain the full details,” DoD spokesperson Lt. Col. Uriah Orland told Breaking D today. UPDATE ENDS.

Sullivan: Defense industry ‘still underestimating’ global need for munitions

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that there are “no plans” for another Ukraine supplemental at this point.