WASHINGTON: What does the three-star director of the Pentagon’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center worry about? “Let me start in 1914,” said Lt. Gen. Michael Groen.

“Yes, 1914 – I see the look on your face,” Groen told the moderator of an online forum Friday at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

1914 was the last time great powers went to war after decades of relative peace, using radically new technology they didn’t really understand. Back then, Groen said, the result was infantry with bayonets and cavalry with lances trying to charge machine gun nests, futilely pitting muscle power against mechanical power. In the 21st century, he fears, “the Information Age equivalent of… lancers riding into machine guns” is using traditional command, control, and planning processes against an adversary using artificial intelligence, pitting human brainpower against machine speed.

Groen knows what he’s talking about first-hand. In his decades-long career as a Marine Corps intelligence officer, serving everywhere from Iraq to Central America to the NSA, he’s spent a lot of time inside the sausage factory that is a modern military staff.

“We had to integrate intelligence, fires, maneuver, logistics,” Groen said. “These processes were manual. They were stovepiped. They were very slow.”

As intelligence officers, “we do assessments [of the situation]; we couldn’t really confirm them, but we would try to figure out what’s true,” he said. “You’re briefing the commander, who’s got decisions to make. You’re going to brief him on PowerPoint, and you’re going to have a stoplight chart or whatever that you built yesterday, that doesn’t reflect what the enemy is doing today.”

As a result, he said, “we sent small units into very dangerous places, without access to current intel.” The system just couldn’t get the information from source to analyst to commander to operator fast enough. Even when a unit actually came under fire, he said, all too often, they had to hit the dirt and get on the radio “and wait for some command level to work through…how to support them.”

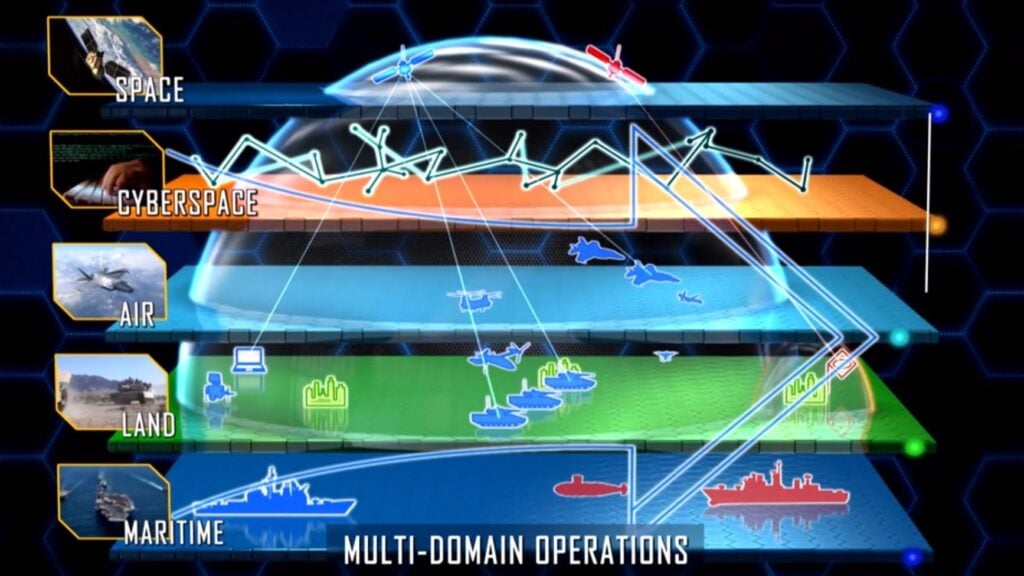

That slowness was survivable, usually, against the Iraqi army or the Taliban. It won’t be against a modern, well-armed adversary, Groen warned. The US military is now trying to build a mega-network for Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) to near-instantaneously share data among its forces on land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

“In an Information Age military, if you are the unit that hasn’t integrated data into your decision making, you are now the weakest link in the Joint Force,” he said. “You are the weakest link that’s going to be exploited by an enemy who is collecting data on you.”

Clausewitz, Boyd, & HAL 9000

Command and control by radio calls and PowerPoint slides does work, more or less, as long as the enemy is moving at the same speed. The fog of war afflicts both sides. Clausewitz famously likened warfare to two men struggling in the dark, neither able to see what the other is doing, making their way by guesswork until they collide and grapple. But what happens when one combatant invents the flashlight?

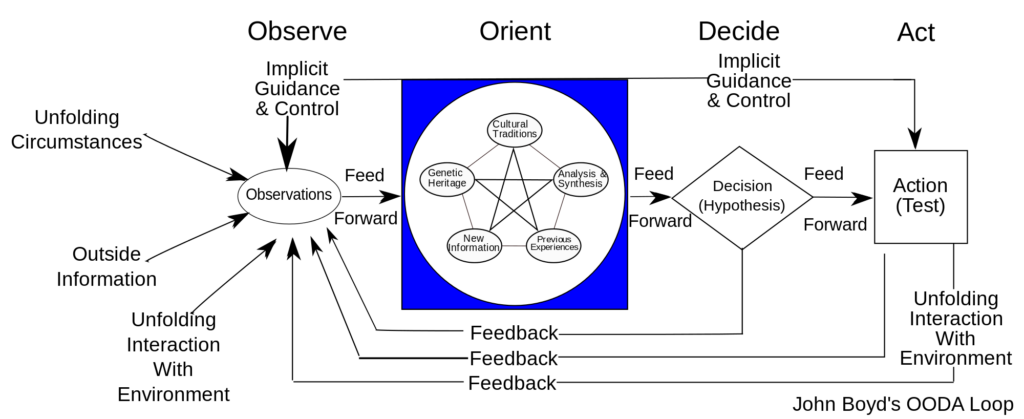

A more modern model is Col. John Boyd’s OODA loop, originally invented to describe jet dogfights in the Korean War but expanded to headquarters and even nations. Boyd realized that life and death depended less on the raw physical performance of the contending planes and more on how easily their pilots could see what was happening and adjust their controls in response – factors that often depended on subtle quirks of cockpit design.

In Boyd’s analysis, each combatant has to Observe the current situation, then Orient themselves correctly to what was actually going on, Decide how to react, and finally Act. A fighter pilot can speed through this cycle in a second. A headquarters staff may take hours or days. A nation’s strategic culture may take decades to adjust to new realities. Consider how the US has struggled to re-orient itself since the Soviet Union fell.

But at whatever level, the side that cycles through the OODA loop faster and more accurately has an advantage that compounds over time. If your cycle is faster than mine, then by the time I’ve Observed the situation, Oriented to it, Decided, and Acted, you’ve already taken action of your own that changes the situation. That means whatever decision I made is already out of date. If I keep lagging, I’ll fall further and further behind, my decisions increasingly disconnected from reality, until I’m ordering units that you’ve already destroyed to reinforce positions you’ve already overrun.

The classic example here is not 1914 but 1940, when the French army’s high command descended into a collective nervous breakdown in the face of German blitzkrieg. The decisive factor wasn’t tanks – the French had more, and mostly better-armed – nor airpower, but the quicker decision cycles of German commanders. The mental quickness of Blitzkrieg was made possible by a more flexible doctrine and an enthusiastic use of radio, which the Germans installed in every vehicle they could, while most French tank commanders were expected to make do with signal flags.

What’s the 21st century equivalent? Strategists in the US, Russia, and China are all increasingly convinced it’s artificial intelligence. The American military in particular sees AI, not as usurping the role of human decision-makers – the malevolent model of sci-fi AIs from HAL 9000 to SkyNet – but as automating the time-consuming grunt work of staff processes. Instead of taking hours or days to cross-reference intelligence reports, come up with an assessment of what’s actually happening, and brief the commander, AI could potentially show the situation unfolding in real time.

Imagine a squad leader who can download a digital map of a building’s interior before storming it, a warship captain who knows a critical shipboard systems is about to fail before it happens, a missile defender whose AI automatically matches interceptors to inbound threats, or a joint commander who can marshal jets, helicopters, drones, and hypersonic missiles against a critical target while an AI swiftly deconflicts their paths through hostile airspace.

“It’s not a panacea,” Groen warned the CSIS audience. “Friction will always be with us. But, reducing that friction to a place that we can create tempo, [outpacing] the enemy’s speed of action, is really what we’re after here.”

Multi-Domain Operations, or All Domain Operations, envisions a new collaboration across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace (Army graphic)

Actually realizing the potential of artificial intelligence takes more than buzzwords. That’s why the JAIC is building a cadre of expert advisers and a cloud-based Joint Common Foundation to help organizations across the Defense Department grow their own AIs — a WWII “victory garden” approach.

Typically, “the first thing you do in an enterprise is you apply AI to your existing workflows, [so] you’re not spooking the herd,” Groen said. “But that will only get you so far.” At some point, you need to move beyond doing things the old way, only faster, to doing things in a different way.

Anyone reading this article on their phone has already made this kind of leap in their daily life. Being able to access information instantly, at any time, as often as you like, makes a smartphone user’s decision-making processes qualitatively different, not just faster, than those of somebody who has to walk to the library to check the facts. It even allows entirely new business models, from e-books to Uber, that were just not possible before.

How might AI technology transform warfare? We don’t know yet, Groen said, but we’d better figure it out.

“We are surrounded by the artifacts of the Information Age. We’re familiar with them, we use them every day, we’re using them right now,” he said on Friday’s webcast. “But I don’t know that we’ve really thought through the implications of the Information Age on warfare.”

That’s uncomfortably similar, Groen worries, to how the commanders on both sides in 1914 lived in a world being transformed by technology and failed to see its lethal impact on the battlefield.

“These guys were citizens of the Industrial Age,” he said. “They’ve seen an internal combustion engine, they’ve probably ridden in a train… They’ve heard of airplanes and talked on the telephone or whatever. All of the artifacts were there, yet here these guys are, these lancers and cavalry units, charging right into the face of machine guns.”

“It’s up to us to act and act now,” Groen said, “so that we don’t miss this transformation, so… we don’t have lancers riding into machine guns, or the Information Age equivalent of that.”