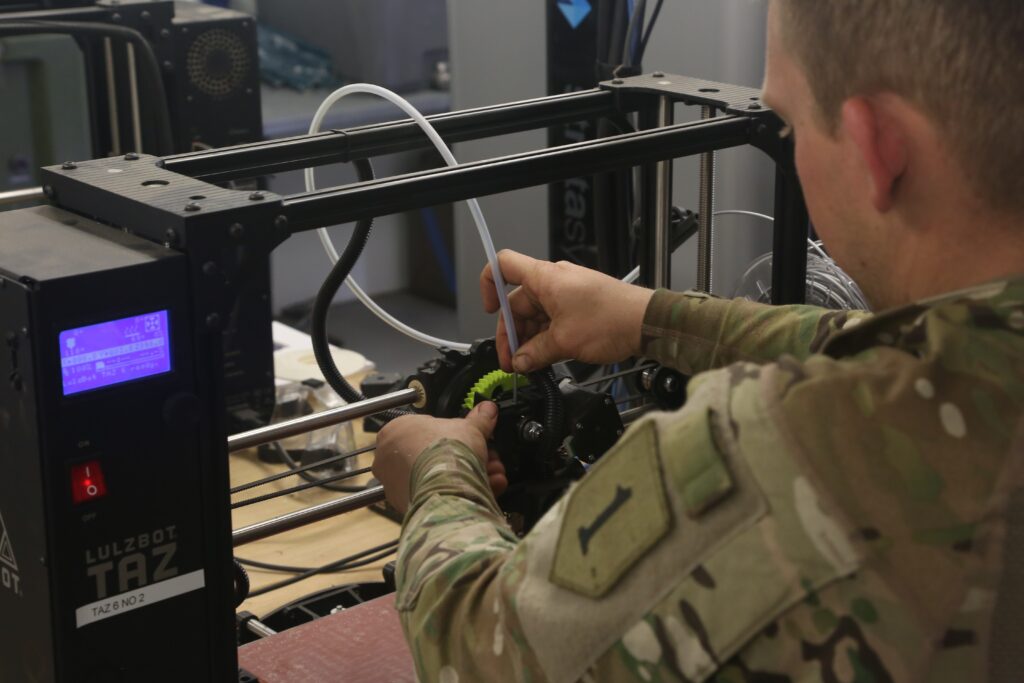

WASHINGTON: When the Army first fielded heavy-duty 3D printers to its combat divisions, maintenance troops were excited by the potential to print their own spare parts in the field, on demand, without waiting days, weeks, or months. But they quickly ran into a problem. Before you can print out a part, you need a detailed 3D model of it, and for most parts, those models don’t exist.

So Gen. Ed Daly, the new chief of Army Materiel Command, is pushing to get 5,000 parts on file in the next 12 months – and that’s just the beginning. The crucial element in all this — lots and lots of accurate, well-organized, and easily accessible data.

In the 20th century, America’s military might depended on our ability to move millions of tons of physical stuff around the world. In the 21st century, it might depend just as much on our ability to move 1s and 0s.

Look at the Army’s experience with 3D printing. “When I was the Chief of Ord, I was very frustrated” about the new 3D printers in the Army’s deployable machine shops, Daly told me in an hour-long interview. “That was a great piece of equipment to be fielded, but I felt like units at the tactical level, the allied trades personnel in maintenance companies, were being constrained because they didn’t have access to a data repository.

“Unless they built the 3D printer design themselves it was very, very difficult,” he said. “We’re finally starting to realize that that equipment is only as good as the enabling … digital thread. You need… a data repository of all the 3D drawings,” Daly said.

Daly’s immediate goal? “It’s a race to 5,000,” he told me. “I want to get to 5,000 [parts] by the end of calendar year…5,000 National Stock Numbers in the data repository that can be used at the tactical edge.”

That requires buying data rights from contractors, creating 3D drawings of old parts where none now exist, and even taking apart entire helicopters and armored vehicles to analyze every component. Then the Army has to take all that data, clean it up, put it in standard formats, and upgrade its global communications networks to make it accessible even to combat units deployed in war zones overseas.

“It’s just not in [stateside] depots, arsenals, and ammunition plants,” Day emphasized. “Our vision within the Army is really to take advanced manufacturing…all the way to the tactical points of contact.”

From ‘Iron Mountains’ To Digital Logistics

The sweet spot for 3D printing is churning out parts that meet three criteria. They’re hard to get through normal channels, often because the original manufacturer went out of business; they’re not essential to safe operation of equipment, because that would require time-consuming testing and certification; and they’re simple enough for maintenance troops or depot workers to create their own digital designs.

But the Army has much bigger ambitions. Cargo ships, planes, helicopters, truck convoys, and supply depots are increasingly vulnerable to attack by precision-guided missiles. The Joint Staff has charged the Army — which provides supplies to all the services, not just its own units — to develop a new concept for “joint logistics under attack,” a vital part of future All-Domain Operations. And the service’s own official concept for future conflict, Multi-Domain Operations, says individual combat brigades must be able to operate up to seven days without stopping for resupply.

That goal is impossible with the traditional logistical system, which relies on moving thousands of tons of fuel, ammunition, rations, and spare parts around the world and building up “iron mountains” of stockpiles. So – while logistics isn’t officially one of the Army’s Big Six modernization priorities – the Army is investing in a host of technologies to reduce its dependence on long and vulnerable supply lines:

- electric-drive vehicles and mobile nuclear reactors to reduce fuel demand;

- unmanned supply drones and trucks, to reduce the number of personnel deployed and at risk;

- AI-driven predictive maintenance, to reduce the amount of time equipment spends out of service;

- data analytics for determining exactly what supplies and spares a unit needs, to reduce just-in-case stockpiling;

- and 3D printing, to reduce the number of different spare parts a unit has to schlep along with it in case something breaks down.

“We’re really going after some big game changers … not just incremental change,” Daly told me. “That is going to change the complexion of sustainment on the battlefield.”

Today, logisticians make do with a bewildering variety of different specialized systems to track, order, and manage different kinds of supplies.

“We’ve got GCSS-Army,” Daly said. “We’ve got GFEBS, AESIP… and then we have about 500-plus other legacy systems that are out there.” Only some of these, like CAISI and CSS VSAT, are designed to be easily deployed with combat units – but even those frontline logistics systems run on different networks, using different hardware and software, than the tactical command-and-control systems used to coordinate combat operations.

The goal is to modernize this alphabet soup of systems so they form one coherent meta-network extending from AMC HQ and maintenance depots in the United States all the way to frontline troops. “What we have done in the past is that the sustainment has always been separate from the tactical network,” Daly told me. “Now, it’s going to be integrated.”

Show Me The Data

Building an integrated global network is itself a tremendous technical challenge. So is securing it against cyber attack, as our readers know from our coverage of All Domain Operations (ADO). But the network just provides access to the data. To make something like 3D printing work, you also have to collect the data.

“We have two systems right now,” Daly told me. “Windshield is the data repository for one, which is not very user-friendly, but that’s what our engineers use. And the other system is called Raptor, and that’s more user-friendly, but it is very immature.” Army Materiel Command is now studying options to move beyond these separate systems to an “overarching digital thread… so that anybody, anywhere in the world, can pull from that data repository,” Daly said. “That should be in place by early summer.”

Once you set up a data repository, how do you fill it? The Army needs to pull from two directions, Daly said: It has to go back into its existing inventory of parts, which often means creating digital 3D blueprints where none exists, and it has to go forward with its new weapons programs, ensuring that those contracts include 3D data packages from the start.

“For the legacy systems… unfortunately, for about 99 percent of our stock numbers, we don’t have 3D computer-aided design instructions,” Daly told me. “We’ve got to negotiate the tech data. We’ve got to do first-article testing. [We have to] have the certification that, if we 3D print it, it’s safe to put on a vehicle or system.”

“That’s going to take time,” he said. “That’s that race to 5,000.”

But “over time, the next 10, 15 years, we’ll be exponentially better at having this repository,” Daly said. Already, Army Materiel Command’s subordinate Life Cycle Management Commands – AMCOM for aviation & missiles, CECOM for communications & electronics, TACOM for tanks & other vehicles, JMC for munitions – are working with Army Futures Command, which leads modernization, and the acquisition Program Executive Officers, who actually buy everything for the Army. Together, they’re thrashing out the complex technical, contractual, and legal details of how to get the intellectual property rights and technical data packages to allow 3D printing for every new weapons system.

“How do we buy 3D drawings?” Daly asked. “How do we buy a portion of the tech data?”

“We don’t necessarily have to buy all the tech data,” he emphasized. “We just have to buy the right tech data and get the right 3D drawings.”