WASHINGTON: The Army and Air Force have been told to stop talking in public about their feud over long-range strike for All Domain Operations — signaling that the decision about who does the mission now is in the hands of higher powers.

It may be resolved by a review by the powerful CAPE in time for the 2023 budget chop, experts say. Indeed, Congress may require such a study by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment & Program Evaluation shop — and perhaps also an independent study to look at force posture needs — in the fiscal 2022 defense policy bill.

The question of how to most cost-effectively organize the services to wage high-speed warfare worldwide, particularly against China in the far-flung Indo-Pacific theater, “should be a topic of significant analysis on the part of DoD,” said Mark Gunzinger, director of future programs at the Mitchell Institute. “And if DoD does not instigate it on their own … I would hope the Congress would.”

Multiple sources confirm that congressional staffers from the House and Senate Armed Services Committees are discussing what should be done with Air Force and Army officials, as well as with various think tanks and service-related associations.

“Service tensions are boiling over into public view, and it ain’t pretty,” one expert said.

The long-simmering turf war between the two services boiled over last Thursday, when Gen. Timothy Ray, head of Air Force Global Strike Command, called out as “stupid” the new strategy by Army Chief Gen. James McConville to expand the “speed and range” of its ground mission.

Most controversially, the Army is developing multiple types of long-range missiles, such as hypersonics, to destroy targets, including advanced anti-aircraft defenses at ranges historically reserved for bombers — raising the prospect of the Army clearing a path for the Air Force when it’s historically been the other way around. Taking out air defense batteries has long been a core Air Force mission, known as SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses).

“This is the natural result of a military asked to do too much with too little for too long,” Sen. James Inhofe told me in an email statement. “With too few resources to meet the strategy, people will naturally spend significant time and energy fighting for resources. …

“However, we do not have time to litigate parochial fights between the services or other actors at the Department of Defense,” the powerful Republican minority leader of the SASC stressed. “The Chinese are outpacing us, and we need to spend every waking moment focused on catching up.”

Inhofe further took a predictable swipe at President Joe Biden’s expected 2022 budget plan — which would keep DoD spending to 2021 levels and not include a bump up for inflation — claiming that this will force “the military to make impossible choices.”

The Biden administration is already scrambling to wrap up the 2022 budget request by June. The annual federal budget proposals officially are due to Congress in February, but new administrations (and even entrenched ones) often blow the deadline. The White House is currently expected to release the top-line budget for DoD and other agencies tomorrow.

Defense analysts say there simply isn’t enough time to thoroughly compare project costs of the two services’ long-range strike plans for the 2022 budget exercise, much less how thoroughly might vet the new operational concepts required for globalized, all-domain warfare in heavily contested environments.

Even to affect the 2023 budget drill inside the Pentagon, former Pentagon staffers say, a full-fledged study of Army vice Air Force plans by the CAPE would have to be done on a quick-turnaround basis. This is because much of the work for that five-year defense plan (POM) has already been finished by the Joint Staff and the services to meet the long lead times required by the Soviet-style budget system.

Further, the new administration hasn’t got its full leadership team in place at the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The civilians at OSD that would normally step in to quash such “family feuds” among the military services — usually before they spill into the public domain. DoD civilian leaders essentially have told the services, as noted above, to shut up already and directed that all media inquiries on this topic to OSD public affairs.

How the joint force will kill long-range targets hundreds or even thousands of miles away — what the Army calls long-range precision fires — is one of the four key subcomponents of the Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC). (Somewhat ironically, work on that subconcept is being spearheaded by the Navy, which has so far stayed neutral between the Army and Air Force, at least in public.) The JWC will define how the US fights Russia, China and other near-peer competitors across the land, air, sea, space and cyberspace domains at machine-speed.

“As we develop that Joint Warfighting Concept, underneath it there are four supporting concepts that, more broadly speaking, are now referred to as ‘four functional battles.’ And those four supporting concepts, those four functional battles, are simply put: global fires, contested logistics, all domain command and control, and information advantage,” Gen. John Hyten, vice chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the AFCEA DC’s 5G Defense Technology Summit yesterday.

However, the Joint Chiefs generally are loathe to choose among each other’s priorities — despite their notorious ferocity in fighting for their own budgetary turf behind the scenes.

“I have no hope that the Joint Staff will [resolve the mission overlap],” the former Pentagon staffer said. “They seek consensus.”

To whit, the emerging JWC does not take costs into account. Instead, when it rolls out late this spring, it will lay down the idealized precepts of how the services will fight together and Combatant Commands will share missions and areas of responsibility.

“Policy is not the job of the Joint Force. Policy is not the job of the Joint Requirements Oversight Council,” Hyten said. Instead, that is the job of OSD.

“It’s ultimately a political decision, and … this demands a strong and fully staffed OSD. That doesn’t seem likely until much later this year,” said Mackenzie Eaglen of the American Enterprise Institute.

A number of analysts cautioned, however, that the new American way of war means that roles and missions in future likely will be more fluid than in the past.

“Heed not the siren call that says that only one service or domain or capability will service the set of strike missions, plural,” tweeted Tom Karako, a missile expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “That siren has a beautiful voice. But she deceives.”

Karako’s thoughts echo those expressed recently by Hyten, who has been stressing that the idea is to have multiple options for multiple scenarios that perhaps are even taking place at the same time.

But while all that may be true, several analysts took a more cynical view — saying that whatever might be best isn’t going to be the deciding factor in a cost-constrained environment.

“I think that service overlap and redundancies are unaffordable right now—regardless of merit,” one long-time defense watcher said bluntly.

At OSD, drilling down into cost-benefit tradeoffs of current and planned weapon systems is CAPE’s bread and butter, defense analysts and former Pentagon staffers explain. But CAPE is made up of budgetary and programming experts, not technical experts or professional military officers.

“We’ve studied this to death,” said Mark Lewis, who recently joined the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) after stepping down as acting undersecretary for research and engineering (USDR&E). “I mean, we understand the value of these systems. So what we really need, the next step, would be the actual force posture — how many different types of weapons used in how many different ways, considering both a European scenario and an INDO-PACOM scenario.”

This is where Congress is likely to weigh in, experts say. A traditional method for attacking tough inter-service budget/policy tradeoffs has been for the Armed Services Committees to mandate that DoD direct a service-independent federally funded research and development organization (FFRDC) to look at the problem and make recommendations. For example, both the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) and MITRE have been involved in advising DoD on hypersonic technology.

Army Math, Air Force Math

The 2018 National Defense Strategy Commission, mandated by Congress in the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), actually recommended that DoD pursue both new long-range (aerial) strike and long-range ground-based fires as part of the military’s pivot back to ‘great power competition.’ It reads:

“Protecting U.S. interests from China and Russia will require additional investment in the submarine fleet; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets; air defense; long-range strike platforms; and long-range ground-based fires.”

Thus, the Army since 2018 has been heavily investing in new ground-based missile efforts (such as the Precision Strike Missile, known as PrSM) under its Multi-Domain Operations concept — with long-range precision fires at the top of its ‘big-six’ major modernization priorities.

The Air Force similarly has been pumping R&D money into the B-21 bomber that can strike deep in adversary territory; drone projects designed to improve the survivability of its piloted bomber and fighter fleets (such as Skyborg) and to maximize weapons delivery for SEAD (such as Gremlins); and artificial intelligence to maximize all facets of aircraft operations.

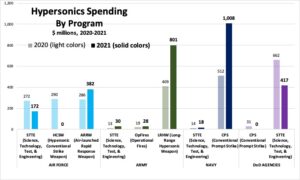

And, as Sydney and I reported last April, both services are to practically throwing research money at hypersonic missiles — as are the Navy and DoD agencies. The myriad projects account for about $15 billion in investment between 2015 and 2024, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found in a March 22 report.

That said, as several experts pointed out, the Army has been investing much more than the Air Force in hypersonic technology — and arguably is farther along with its efforts. For example, the Army is marching ahead with plans to field its Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) in 2023.

The Air Force has seen upgrading stand-off bombers (i.e. the B-1B and the B-52) with hypersonic weapons as less of a priority than funding the penetrating B-21. The service’s first booster flight test for its AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) was on April 5 — and it failed. The problem was a “glitch” that prevented it from launching off the B-52H bomber designed to carry it, the service announced April 6.

In any event, as hypersonic programs move out of early R&D and into actual production, both services will face a budget bow wave, pretty much everyone agrees. And that bow wave is just not going to be supportable, especially in an era when DoD spending is likely to grow very little if at all given the pressures on the US economy stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

As GAO summed up:

“Without clear leadership roles, responsibilities, and authorities, DOD is at risk of impeding its progress toward delivering hypersonic weapon capabilities and opening up the potential for conflict and wasted resources as decisions over larger investments are made in the future.”

The Air Force and its supporters argue that penetrating bombers, even adding in the costs of new hypersonic missiles, are orders of magnitude cheaper than any ground-launch missile system. Ray called the Army’s hypersonic missile plans “brutally expensive.” Further, they say, the Air Force already is doing the long-range strike job.

“I just think it’s a stupid idea to go invest that kind of money to recreate something that this service has mastered,” Ray said.

“The range of a weapon increases its size, which increases its costs,” said Gunzinger, no matter how it’s launched. “It’s just a fact.” And “surface-launched weapons tend to be more costly than air-launched weapons for the same size and payload.”

“The Air Force needs to come to the table with its numbers, its facts and analysis. And it all comes down to, what’s the volume of targets you need to hit? What are the ranges in play? And what is the business case?” said Doug Birkey, of the Mitchell Institute, who waxed confident that the Air Force would win on cost.

Army officials and their supporters counter that it is doing what it is supposed to be doing under both the National Defense Strategy and the pending JWC: providing more options for commanders to use on a globalized battlefield.

“We need a comprehensive approach to take this down,” Army Brig. Gen. John Rafferty told Sydney this past July. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

The Army is making “a compelling case … including for new places and bases to host capabilities in the Asia-Pacific,” said one analyst who covers both services.

In addition, Army leaders stress that the idea isn’t to cover Japan or Poland with missile batteries. “We’re pretty modest in our goals for quantities,” Rafferty said, “recognizing [both] cost [and] the effect that can be gained by a small unit of these — in the context of a joint force, not in and of themselves.”

It’s important “to make sure that the right questions are being asked, and the right things being measured,” one expert said, leaning into the Army argument. “It’s not whether or not it’s cheaper to deliver a gravity bomb with air superiority, as opposed to a standoff missile in a contested environment—of course it is. But that comparison is comparing apples and oranges. It’s a denied or contested environment, and opening up windows of opportunity is absolutely going to require both standoff [capabilities.] It is also important to properly respect the gravity of the threat, and the degree to which a near peer would be targeting airfields … [and the] cost of operations in or through the domain.”

The reality is that there simply are not any comprehensive, long-term cost studies for either service’s plans, experts said. This is in part because all of the efforts are still in R&D. Many projects are classified, with no public funding profile.

It’s also just difficult to agree on what to include in the true cost of a single strike. A single air-launched munition dropped near the target can be smaller and cheaper than one launched from the ground hundreds of miles away, but a bomber is more expensive than a truck-mounted missile launcher. Do you include the cost of transporting the ground launchers, bomber escort planes or ground security troops? What about the vast array of satellites, drones, spy planes, and command-and-control networks that both air-launched and ground-based weapons depend on to find their targets in the first place?

Amidst all these variables, it should be obvious that Army math will under almost no circumstances equal Air Force math — even when the question of trade offs comes in front of Congress during budget debates.

“The Army states are going to support the Army; the Air Force states are going to support the Air Force,” said one advocate jadedly.