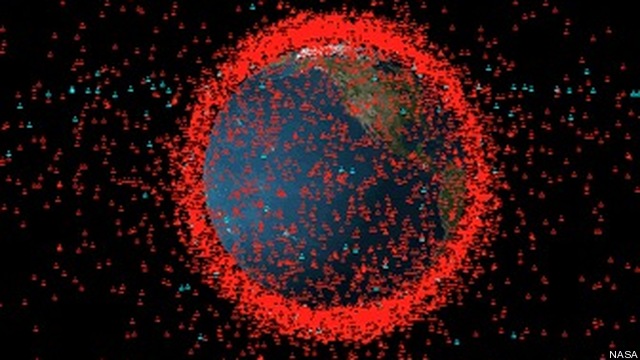

Satellites and space debris in orbit around Earth. (Aerospace Corporation)

WASHINGTON: Frustrated industry officials, scientists and experts are pushing the US government to take on responsibility for cleaning up the space environment — starting with debris created by federal agencies, some of which dates back to the early days of the Space Age.

“One of the most important things that the government could do is that 28% of the debris in Low Earth Orbit was created by the US government. A lot of this was, you know, part of winning the Cold War. And like many other environmental messes that were made in winning the Cold War, this one should be cleaned up too,” Jonathan Goff, vice president of on-orbit servicing at exploration startup Voyager Space Holdings, said Thursday during a town-hall-style virtual meeting on space debris sponsored by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

“If the US Navy had a derelict ship sitting in sovereign waters creating a safety hazard, the Navy would go out and grab that ship… or it would more likely hire a salvage company … and go ahead and bring that ship back to shore,” Doug Loverro, former head of Pentagon space policy during the Obama administration, told the meeting. “That that kind of responsibility has been around for seafaring nations for decades. And I’m not sure why we don’t see the same responsibility in government for their derelict ships and their derelict bodies that are in space today.”

Taking responsibility, a number of participants said, includes providing more federal government funding for further development and on-orbit demonstration of emerging tech to help kickstart the market and improve the business case for wary investors.

“If the government would take responsibility for that and would say that they are going to pay for folks to go ahead and get rid of those derelict ships and those derelict [rocket] bodies, many of the business aspects of this that we’ve spoken about would be clear,” Loverro added.

Several participants pointed to the Defense Department’s efforts to spur tech innovation in the field of so-called active debris removal via its SpaceWERX innovation hub through the use of funding authorities such as Small Business Innovation Research/Small Business Technology Transfer grants as a model for other agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA, to emulate.

However, it’s not just funding that is required to handle the burgeoning debris problem, participants said, but also the establishment of an agency focal point or an interagency group to coordinate cross-government action.

“It’s no longer an option to hide from the problem or punt it down the road. Active management of the space environment requires our immediate attention, and the role of the government should be to display leadership in supporting the development — not just the technologies, also financial incentives and the policy underpinnings — to allow remediation services to thrive,” said Charity Weeden, vice president for global space policy and government relations at debris removal startup Astroscale.

“Remediation is an interagency issue,” she added. “So there needs to be a top-level coordinator [who] can take into account the aspects of all the departments agencies that would be involved. We think NASA is the right place initially, we’re open for other options and debate on this.”

The two-hour “listening session” provided industry reps, scientists and interested members of the public with an opportunity to weigh in on the White House’s “National Orbital Debris Research and Development Plan” [PDF] issued last January in the waning days of the Trump administration.

In early November, the Biden administration announced that OSTP would be updating the plan, which had been criticized by a number of experts as simply touting more research on already widely understood problems, and opened a public comment period through the end of the year. The request specifically asked for input on “what R&D areas are priorities for government-sponsored initiatives/coordination, the roles of academia, nonprofit, and industry actors in addressing these actions, and potential avenues for coordination between actors across public and private sectors.”

To follow up, on Dec. 17 OSTP announced [PDF] that it would hold two town-hall type virtual opportunities for oral comments as follows:

- Jan. 13, Debris Mediation: “the active or passive manipulation of debris objects to reduce or eliminate the risk they pose to operational space assets. This may include fully removing debris from orbit, moving debris from orbits that pose a high risk to operational spacecraft into lower-risk orbits, and finding ways to repurpose or recycle existing debris.”

- Jan. 20, Debris Mitigation: which refers to “limiting the creation of new debris through deliberate spacecraft and launch vehicle design choices.”

The Thursday meeting at times resembled the TV comedy Seinfeld’s Festivus celebration’s “airing of grievances,” and at other times descended into what could only be seen as shameless self-promotion of various tech companies’ wares. That said, there was widespread accord on a number of recommendations.

For example, aside from the issues of responsibility and funding, numerous commenters noted the need to lower the 25-year time deadline for removing defunct satellites from LEO — which the Trump administration’s 2019 rewrite of US space debris mitigation guidelines retained after a fierce inter-agency fight.

Another common thread was on the need for the Commerce Department to quit stalling on providing NOAA’s Office of Space Commerce adequate funding and more authority to take on the role of civil space traffic management, relieving the Defense Department of the job of warning commercial and non-US operators of potential on-orbit collisions, including with debris.

Indeed, President Joe Biden’s nominee for DoD assistant secretary of space policy, John Plumb, in his confirmation hearing Thursday, called space traffic management “absolutely essential” and pledged to help make the transfer of responsibility happen.

Millennium Space Systems is delivering on critical missile tracking constellation

With programs like MTC, Millennium Space Systems is redefining what it means to be an operational prime – rapidly delivering operational small sat constellations on rapid timelines.