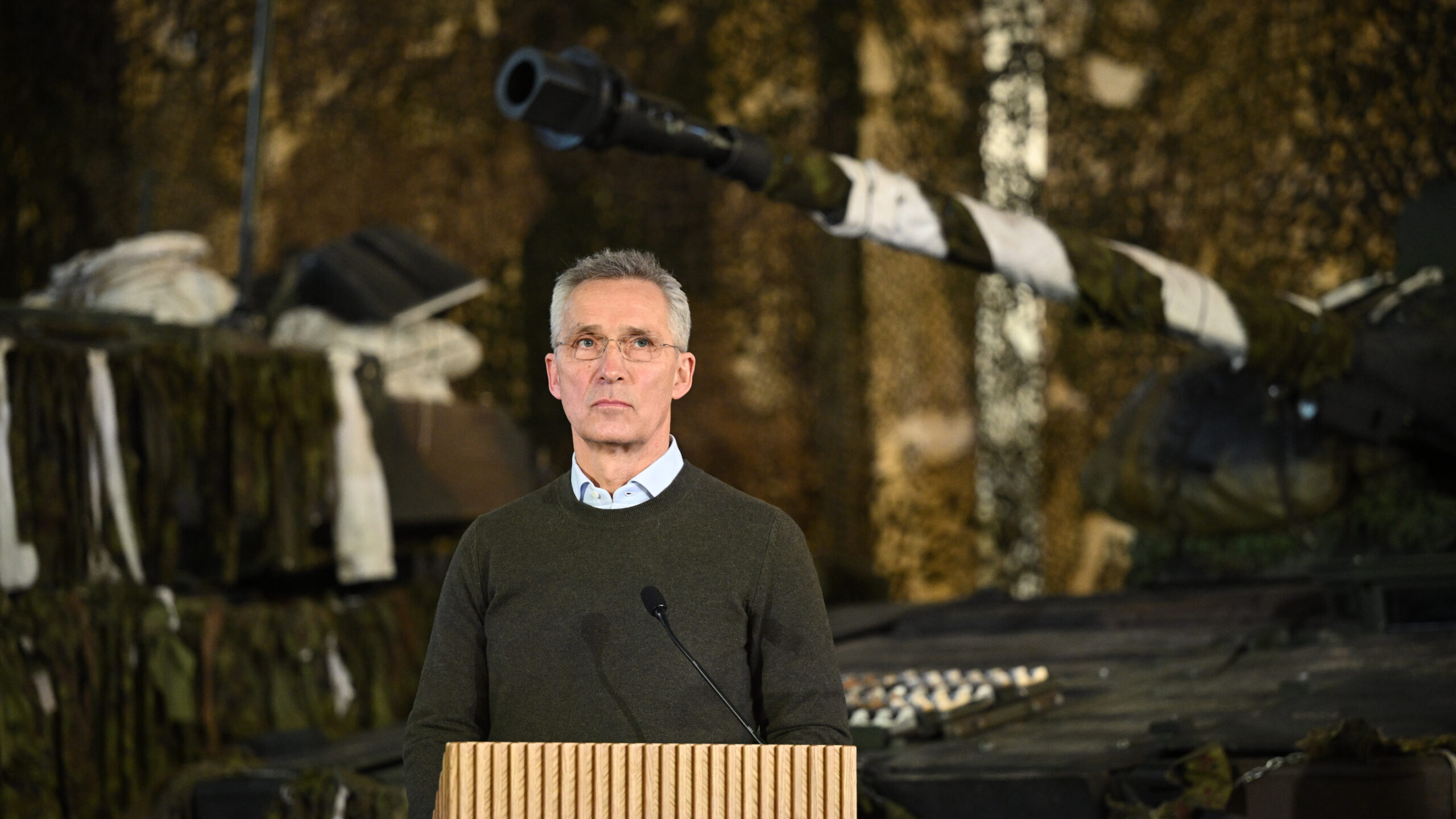

Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary General of NATO, speaks during a joint press conference at the Tapa Army Base on March 1, 2022 in Tallinn, Estonia. (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON: This week Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrapped up his tour of NATO eastern flank countries Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, hoping to reassure nervous allies. Russia’s naked war of aggression against nearby Ukraine and its constant threats and bullying of its neighbors explain why all eyes in the trans-Atlantic alliance are now fixed not only on Ukraine, but also on NATO’s vulnerable Baltic members, where Blinken was met with a warning on his arrival in Estonia.

“Frankly, deterrence is no longer enough and we need forward defense here in place because otherwise it will be too late, Mr. Secretary,” Estonian President Gitanas Nauseda told Blinken bluntly. “Putin will not stop in Ukraine if he will not be stopped.”

In fact Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is just the latest and boldest move by President Vladimir Putin to forcibly impose a privileged sphere of influence on his democratic neighbors. As far back as 2007 he launched one of the largest state-sponsored cyberattacks ever against Estonia, paralyzing the country’s internet for the crime of daring to move a statue of a Soviet soldier from the center of the capital.

In 2008 Russian forces invaded Georgia and occupied two “breakaway” republics because that country expressed an intent to join NATO. When Ukraine tilted West in 2014, Russia forcibly annexed Crimea and launched the separatist conflict in Donbas. More recently Moscow has helped quell democratic uprisings and prop up dictators in Belarus in 2020, and Kazakhstan earlier this year.

As Russian military forces continue trying to bomb Ukraine into submission, it is certainly not lost on US military leaders that Putin’s recently stated demands that NATO halt its expansion and remove military forces and infrastructure from its eastern flank countries suggest where his ire and ambition may be focused next. In the harsh light of the new cold war that is descending over Europe, it’s also increasingly clear that NATO leaders for years wrote checks and IOU’s with the alliance’s expansion eastward that its steadily dwindling defense capabilities couldn’t cover. And Vladimir Putin noticed.

“If Putin was willing to launch a full-scale invasion of another country on the doorstep of NATO, we have to be candid with ourselves that he perceived some signal from the United States and NATO that made him think he could get away with it, and we need to understand those signals that are eroding the alliance’s deterrence,” Martin Dempsey, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told Breaking Defense.

Those signals likely include a steady reduction of US forces in Europe and declining military readiness and capability among European allies; a 20-year US preoccupation with counterterrorism and the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan; a publicly announced US “pivot” to Asia to cope with the challenge of a rising China; an overreliance on the threat of economic sanctions as an adequate deterrence; years of former President Donald Trump browbeating NATO over inadequate burden sharing and threats to abandon the alliance; and the Biden administration’s chaotic military retreat from Afghanistan last year.

“Intuitively I think it’s unlikely that Putin would have ordered the invasion of Ukraine if he hadn’t perceived that the NATO alliance was more vulnerable than in the past, and that that vulnerability was growing over time. So lesson number one to me is that we need a reinforced US military presence in Europe, and the right kind of political statements about the value of the alliance to strengthen its deterrent value,” said Dempsey. Putin has also made clear that he considers himself a historic figure in the mold of Peter the Great, noted Dempsey, and he’s intent on reestablishing Russia’s sphere of influence, including in the Baltics.

President of Russia and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Vladimir Putin watches a Victory Day military parade on Red Square on June 24, 2020 in Moscow, Russia. (Photo by Ramil Sitdikov – Host Photo Agency via Getty Images )

“In Georgia in 2008, Crimea in 2014 and today in Ukraine, he has showed us the lengths he is willing to go to achieve a new Russian empire,” Dempsey said. “So as Maya Angelou once said, ‘When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.’ Putin has repeatedly showed us who he is, and shame on us if we fail to believe him.”

A Vulnerable Alliance

At the height of the Cold War the United Sates maintained roughly 400,000 troops in Europe, spread out primarily in Germany, the United Kingdom and Italy. By 2021 that number had plummeted to below 60,000. The Pentagon withdrew the two corps headquarters it once based in Europe, and in 2013 the US Army brought home its last armored units with M-1 Abrams battle tanks Bradley Fighting Vehicles from the continent. Even as it expanded eastward, the alliance also kept an agreement made in 1997 not to permanently station forces in member states bordering Russia.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and capture of Crimea in 2014 served as an initial wake-up call for the alliance. In response NATO formed four multinational battlegroups of roughly a battalion size (800-1,000 troops) led by the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany and the United States, and deployed them forward on a rotational basis to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. At NATO’s Wales Summit in 2014, the allies also agreed to devote 2 percent of gross domestic product to defense by 2024, a target that only three allied countries met at the time.

Yet in the years hence it became increasingly obvious that the threat from Russia was growing at a much faster pace than the alliance was evolving militarily, despite the addition of Montenegro in 2017 and North Macedonia in 2019. Moscow has been engaged in a decade-long military modernization of both conventional and strategic nuclear forces, for instance, and Russian forces gained valuable combat experience in Ukraine and Syria.

Meanwhile, European pillars of the NATO alliance like Germany and Great Britain saw a steady decline in military capability during that time. A 2018 report on the German Bundeswehr by the Parliamentary Armed Forces Commissioner detailed that decline, including transport planes and fighter aircraft that couldn’t fly, submarines that couldn’t sail, and tanks that couldn’t maneuver because of poor maintenance and repair and a lack of spare parts. A severe manpower shortage had also created a gaping 21,000 vacancies in the German officer corps.

The situation for the once globe-spanning British military was not much better. Due to defense budget cuts, London announced in 2021 that it was reducing the size of the British Army to 72,500 troops and just seven combat brigades, the smallest the British army has been in centuries. The number of British tanks under the plan will fall from 227 to 148, the Royal Air Force will lose 24 Typhoon jets, and the Royal Navy will drop from just 19 frigates and destroyers to 17. When the new HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier launched on its maiden voyage last year, it required a squadron of US Marine Corps F-35 fighters to fill out its air wing.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson sits in the cockpit of an Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II during a visit to HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier on May 21, 2021 in Portsmouth, England. (Photo by Leon Neal – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

In 2021, 10 of NATO’s 30 member states reached or exceeded the 2% of GDP target for defense spending, with the average for European members and Canada at 1.7% of GDP, and the United States spending 3.5% of GDP on defense to meet its global commitments [PDF].

Beyond increasing defense budgets, US military experts believe what’s most needed is a change of mindset in the alliance that recaptures some of the muscle memory from the Cold War, when military forces were maintained in a heightened state of readiness and prepared to fight on strict timelines based on the Soviet Red Army’s order of battle.

“We need to recalculate the entire readiness posture of our military forces, because collectively NATO forces are not ready,” said Ben Hodges, former commander of US Army Europe and currently the Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies at the Center for European Policy Analysis. “Germany has three divisions, but they are not ready to fight. The British Army today is way too small. NATO exercises are far too scripted in advance, and they put too much emphasis on ‘Distinguished Visitor Day’ rather than adopting the necessary rigor where you train to failure, and then learn from the experience. The European Union also still has a ton of work to do in terms of prioritizing the movement of military forces on rail lines and roadways so you can efficiently move them across Europe. All of that is hard and expensive, but if you don’t practice those skills and demonstrate those capabilities our adversary is not going to be very impressed.”

Joseph Ralston, who served as Supreme Allied Commander of NATO forces from 2000-2003, remembers participating in annual “Reforger” exercises during the Cold War as a fighter squadron commander based in the United States.

“Every squadron commander and every maintenance shop focused on that deployment to Germany all year long, and we would have to plan on where to sleep, eat and requisition spare parts when we landed in Europe. We also developed good relationships and trust with the local host nation forces,” Ralston said in an interview. “We now need to reclaim that kind of readiness and warfighting mindset in NATO, because we’re in this confrontation with Russia for the long haul.”

A Watershed Moment

Certainly the spectacle of a Russian tyrant invading and attempting to subjugate a major European democracy for the first time since World War II has shocked the world, and transformed the counsels of the trans-Atlantic alliance. Since the crisis began NATO for the first time has activated its Rapid Response Force and is preparing to deploy it to the alliance’s eastern front. The 1st armored brigade of the 3rd Infantry Division in Georgia has for the first time deployed to Germany and collected prepositioned tanks and armored fighting vehicles stored there for an expected move to the east. A brigade combat team from the 82nd Airborne Division has deployed to Poland. In all, the United States has deployed 14,500 troops to Europe during the crisis, with thousands more on heightened alert.

U.S. Army Gen. Mark Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman Ramon Colon-Lopez, speak with Paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division during a visit to Nowa Deba, Poland, March 4, 2022. (U.S. Army Photo by Master Sgt. Alexander Burnett)

In other historic firsts, the European Union and traditionally pacifist Germany are both funding and sending lethal weaponry to Ukraine, along with many other NATO allies. Berlin has halted the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline with Russia and pledged an immediate down payment of roughly $113 billion of defense spending, while promising to exceed NATO’s 2% of GDP target next year. Poland has announced the planned purchase of roughly a division’s worth (250) of Abrams M-1 tanks. Switzerland has broken with its tradition of neutrality to join punishing European Union sanctions on Russia. Reliably neutral Finland and Sweden are now openly debating seeking membership in the NATO military alliance.

Yet against the roughly 190,000 Russian troops assembled for the dismemberment of Ukraine, the allied troops arrayed on NATO’s eastern flank are still insufficient deterrence. The threat is real that Putin will respond to the faltering of his Ukraine offensive and crippling Western sanctions by lashing out in frustration. In an act of desperation, he could move on a weak NATO member state to show alliance weakness and then threaten to employ tactical nuclear weapons against any response, a move actually anticipated in Russia’s “escalate to deescalate” nuclear doctrine. Putin “is unlikely to be deterred,” Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines testified before the House Intelligence Committee on Tuesday. “And instead may escalate – essentially doubling down.”

“I still worry that we are not building up military forces quick enough on NATO’s new eastern front, because we need significantly more military capability deployed in key strategic areas along a front that runs from the Baltics to the Black Sea,” said Ivo Daalder, former US ambassador to NATO and currently president of the Chicago Counsel on Global Affairs, speaking recently at an event hosted by the Council on Foreign Relations. “Because this is a very serious long-term confrontation that we’re going to have with Russia, and we need to start thinking in terms of a return to a containment strategy, and all that entails.”

Curtis Scaparrotti was Supreme Allied Commander of NATO forces from 2016-2019. He believes such a containment strategy would necessarily entail the return of significant US command-and-control and armor capabilities to Europe.

“Putin has surprised us at every turn with his territorial aggressions, and while I don’t think it’s likely that he would move on a NATO nation, the potential is there if he decides to escalate once again. The best way to stop that is to strengthen NATO’s defensive deterrence on its eastern flank,” Scaparrotti said in an interview. That would require NATO scuttling its 1997 agreement with Russia not to permanently station military forces on its eastern flank — an agreement that is hard to honor in light of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

“In the past we relied on good warning time to mobilize US-based forces, but with the massing of Russian forces in Belarus and Ukraine it’s now clear we would have less time,” said Scaparrotti.

At the heart of that defense in the east, both Scaparrotti and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Dempsey would like to see a US armored division and a US corps headquarters for command-and-control once again based in Europe, backed by multi-domain capabilities and forces to provide air and missile defenses, artillery and rocket forces, logistics, engineering, and other enablers, with the armored division stationed on the alliance’s eastern flank.

“Our European allies will also have to step up and take more responsibility for their own defense, but I believe they have awoken to the threat,” said Scaparrotti. “The irony is that Vladimir Putin’s stated goal was to halt NATO enlargement and move NATO forces out of Eastern Europe, and his reckless actions have achieved exactly the opposite effect. He has prompted NATO to strengthen its force posture in Eastern Europe, and convinced countries like Sweden and Finland to reconsider their neutrality and possibly join NATO. Even Switzerland has made the remarkable decision to abandon its traditional neutrality.

“Who would have thought the world would see all of that?”

Iran says it shot down Israel’s attack. Here’s what air defense systems it might have used.

Tehran has been increasingly public about its air defense capabilities, including showing off models of systems at a recent international defense expo.