Members of the Ukrainian forces participate in an urban combat training exercise. (Ethan Swope/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The following is one in a series of regular analysis pieces by deputy editor Sydney Freedberg.

Ukraine’s surprising success against the Russian invasion shows the character of war is changing. While the Russian military has proven itself unexpectedly inept, there are wider trends at work as well — trends that would hinder any invader anywhere in the world.

That’s bad news for China and other countries that might seek to secure more territory through conquest (and for any remaining American neocons who still advocate preemptive wars on the model of Iraq). It’s good news for democracies, whose strategic goals are overwhelmingly defensive, and especially for smaller nations facing a seemingly overwhelming conventional force.

What’s changing and why? The Ukrainian war highlights military implications of three global trends: precision-guided firepower, sprawling urbanization and mass mobilization. This is not the first time they have shown up; the US itself ran into a similar buzzsaw in Iraq. But Russia’s invasion is the clearest example of how these all play out on a modern battlefield, and as Taiwanese officials have publicly said, Chinese strategists should think hard about the implications for any forcible reunification with Taiwan.

Firepower

There’s an ever-shifting balance between firepower, protection, and maneuver that shapes and reshapes the face of war. Throughout history, when the power of long-range weapons outstrips the protection available against them, it becomes more dangerous to maneuver across the battlefield and safer to stay put under cover. That hinders the attack and favors the defense. Examples include how the English longbows of Crecy and Agincourt disrupted the advance of the French knights, how the machine guns of the Western Front imposed the stalemate of trench warfare — and how Ukraine stymied the Russian advance last month.

The most dramatic examples have been the destruction of Russian tanks by Western-made missiles like the British NLAW and the American Javelin. But heavy armored vehicles are the hardest targets and the easiest to upgrade with advanced countermeasures. (The US Army is installing the Israeli Trophy system on its M1 tanks, for instance). The US experience shows it’s much harder to install anti-missile defenses on lighter vehicles, especially the unarmored supply trucks essential to sustaining any advance. And such thin-skinned vehicles are vulnerable not just to high-end anti-tank missiles but to drones dropping much lighter warheads. In fact, one Ukrainian unit, Aerorozvidka, claims to have halted Russian columns with bomb-dropping drones it designed itself. And even unarmed, off-the-shelf commercial drones can pose a serious threat by spotting targets for Ukrainian artillery or ambushers.

The global proliferation of smart weapons — and of long-range sensors to find targets for them — has implications far beyond Ukraine. Both Russia and China have sought to build “anti-access/area denial” defenses that use long-range anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles to stop US forces from intervening in their regions. Conversely, Western experts like Andrew Krepinevich have argued for similar systems to defend the Philippines, Japan, and Taiwan from China, an approach Taipei has publicly pondered in recent years. The concept, in both cases, calls for using land-based weapons to decimate attacking aircraft and warships as they approach, like a vastly scaled-up version of machine guns at the Somme.

An amphibious invasion is particularly vulnerable to such defenses. Unlike land forces, ships can’t take cover, because there’s no terrain to hide behind on the open sea. Unlike air forces, ships can’t move at hundreds of miles per hour to evade attack. Traditionally, navies avoid land-based threats by staying out of range and using the vastness of the ocean to evade detection – but that’s not an option when the objective is to put troops ashore.

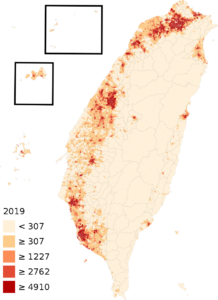

Any Chinese invasion of Taiwan would have to cross over 80 miles of open water — and then fight its way inland across some of the most densely urbanized terrain on earth. Which leads to the next topic:

SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons

Urbanization

Historically, Ukraine has been a highway for invasion: a land of open steppes, wheat fields, and few natural obstacles to the rapid advance of invaders from Mongol horsemen to Nazi tankers. So why have Russian forces failed to seize Kyiv, whose outskirts lie less than 60 miles from their jump-off positions in Belarus, or Kharkiv, just 13 miles from the Russian border?

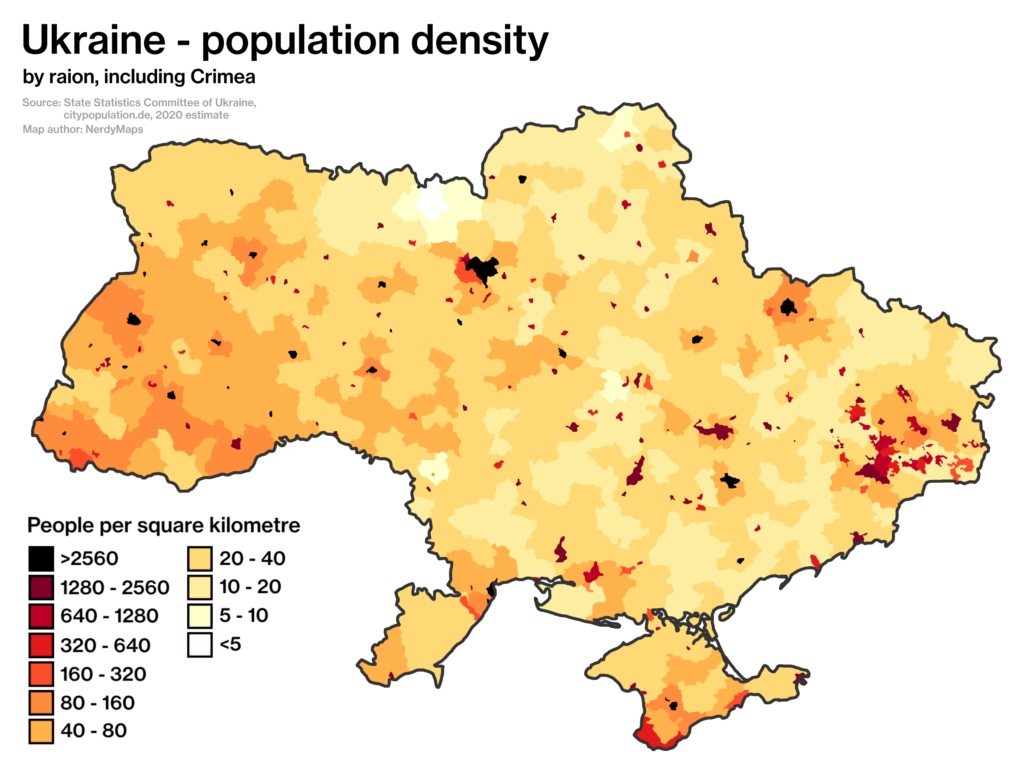

Part of the answer is urbanization, which physically reshapes the landscape in ways that favor the defense. While the natural features of Ukraine remain unchanged, the human geography is very different than in past wars. Ukraine’s population is actually not much bigger than it was when Hitler invaded — a little over 40 million then, versus 45 million today, according to official figures — but the portion living in urban areas has doubled, to 69 percent. A population density map of Ukraine is speckled with cities — each of them a potential fortress.

As far back as the sixth century B.C., warrior-sage Sun Tzu warned against attacking cities, calling it the worst of strategies. 21st century cities are even tougher: They may not have stone walls, but they feature multi-story buildings allowing ambush from above, concrete structures easily converted into bunkers, and tunnels, or even entire subway systems, that let combatants maneuver underground. The sheer complexity of an urban environment is a nightmare for attacking troops, who lack the defenders’ familiarity with the myriad of back routes, hiding places, and potential ambush zones. Bombarding a city into rubble — as Russia is doing in Ukraine — is effective at slaughtering civilians, but from a military perspective it fills the streets with rubble: more cover for the defenders, more obstacles for the attackers’ advance. No wonder, then, that some of the bitterest fighting in modern times has been in urban areas, from Fallujah and Sadr City in Iraq to Mariupol in Ukraine.

SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons

So, traditionally, most armies’ preferred approach to cities is to avoid approaching them at all. But it’s getting ever harder to go around as the global population grows increasingly urban and urban areas sprawl ever further across the landscape. In 1960, just about a third of the world’s people lived in urban areas, according to the World Bank; by 2020, that figure was nearly 60 percent.

In Taiwan, China’s top target, almost 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas. While the island’s population is much smaller than Ukraine’s — just under 24 million as opposed to 45 million — it’s also concentrated in a much smaller land area, so population density is nine times as high (1,709 per square mile vs. 185). And that population is particularly concentrated on the west side of the country, where any Chinese invasion force would likely have to land. (The east coast is not only further from the mainland but also steeply mountainous).

Such dense urban areas don’t only create physical obstacles to invasion: They create human barriers as well. People packed in close proximity to one another can more easily form social networks, mass protests, rioting mobs, or even insurgencies. And modern technology makes mass mobilization easier than ever before.

Mobilization

Russia ruled most of what is now Ukraine for over 300 years. But today’s Ukraine is much harder to subdue. Historically, most Ukrainians were subsistence farmers, living in isolated villages, with only a slow trickle of news and ideas from outside. Today, most Ukrainians live in cities, and over 60 percent of them have smartphones. For traditional peasants, war and politics were like the weather: inscrutable, dangerous, often disastrous forces that could be endured but never affected. For modern netizens, warfare is interactive, with social media urging them to resist, protest, enlist, make Molotov cocktails, attack supply convoys, and more. Images of victories and atrocities go viral, and leaders like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky can appeal directly to the people.

This phenomenon long predates the internet. Churchill famously rallied British resistance over the radio. Before that, large-scale printing of newspapers, pamphlets, and books fanned the flames of popular resistance movements as far back as the American Revolution. Dictators have exploited mass media as well, with Hitler, Stalin, and the like using propaganda to whip up their populations for total war in ways pre-industrial despots could never equal. The unifying factor is mass communications enabling mass mobilization, but the internet is the latest and most effective form. (Witness the rise of QAnon and the Jan. 6 riots in the US itself).

Members of the military carry a large Ukrainian flag during Ukraine’s Independence Day parade on August 24, 2021(Brendan Hoffman/Getty Images)

Of course, websites can be hacked, transmissions jammed, printing presses seized. But even if an invader can shut down communications during wartime — and Russia’s failure to do this in Ukraine is glaring — it’s largely too late if strong national identity has already formed. Years of exposure to mass media helps create such identities by exposing populations to a common language, ideas, and experiences, creating what scholar Benedict Anderson called an “imagined community” that goes far beyond people’s face-to-face connections. And once people identify with something beyond their village, they’re more likely to mobilize themselves to defend it.

In Ukraine today, it’s clear that millions of Ukrainians identify with the national cause, strongly enough to fight for it. What about Taiwan? It is one of the world’s most wired and mobilized societies. As of 2021, 98 percent of the population had a smartphone. 67 percent of them typically turn out for elections — up to 75 percent in 2020.

Now, historically, both Beijing and Taipei agreed that Taiwan was inextricably part of a united China: They just disagreed on who should be in charge. But in recent opinion polls, 68 percent of Taiwan’s population identified themselves as Taiwanese, less than two percent as Chinese, and 28 percent as both. 64 percent said they would “absolutely” or “probably” fight to defend Taiwan.

Those figures suggest a Ukrainian-style territorial defense militia would find plenty of recruits in Taiwan. Armed with modern missiles and drones, and defending urban terrain, they could be a formidable obstacle to any Chinese invasion.

Aggression is hardly obsolete, and China is much stronger than Russia. But Ukraine suggests the right kind of defense is increasingly effective, and democracies around the world should look to its example.

Move over FARA: General Atomics pitching new Gray Eagle version for armed scout mission

General Atomics will also showcase its Mojave demonstrator for the first time during the Army Aviation Association of America conference in Denver, a company spokesman said.