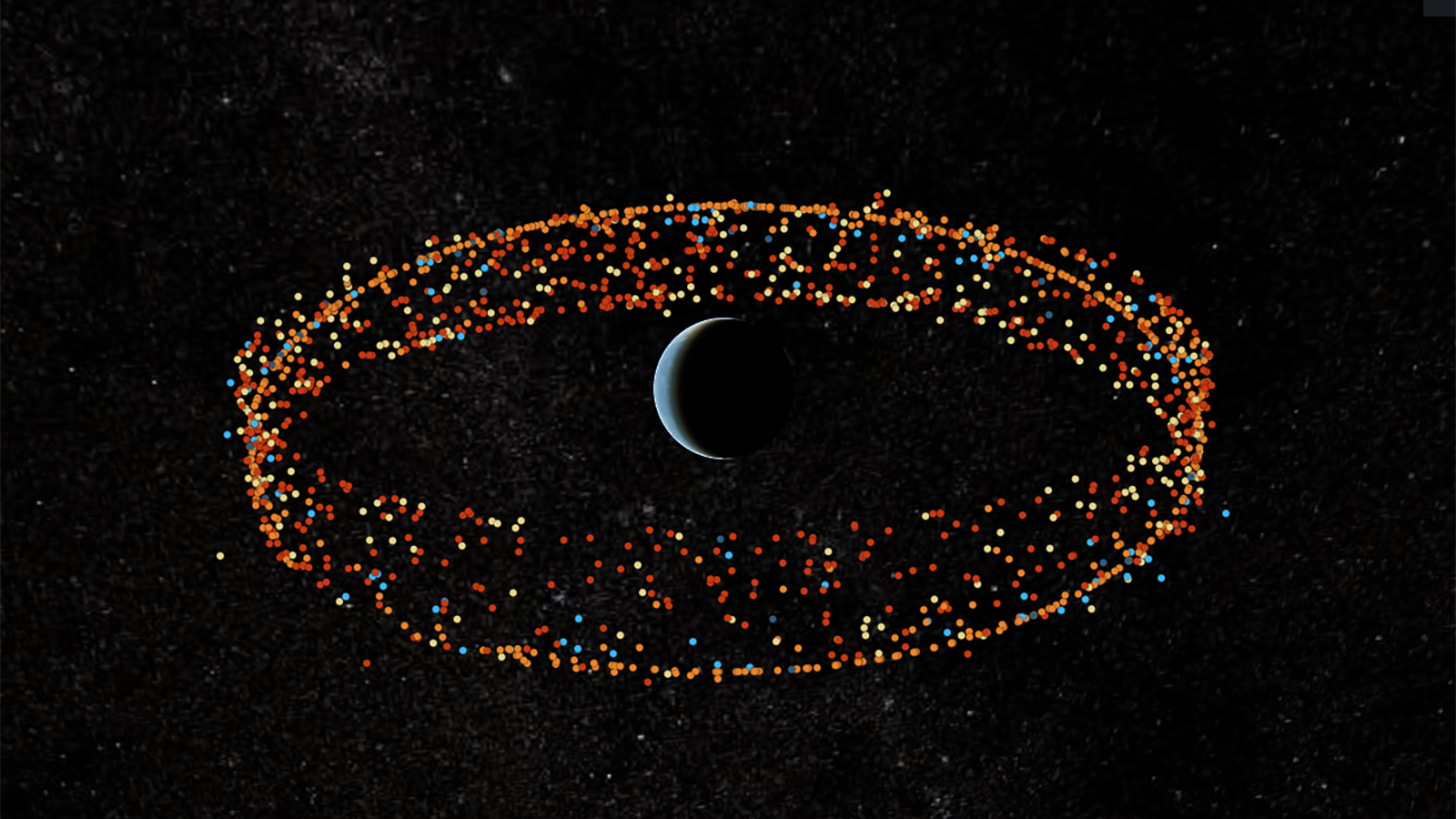

The Satellite Dashboard is an example of an open source tool to monitor close approaches of satellites and debris in space, produced by the Center for Strategic and International Security, the Secure World Foundation, and the University of Texas at Austin. (The Satellite Dashboard)

AMOS 2022 — The rapid increase in constellations comprising large numbers of satellites pose serious environmental hazards in space and to the atmosphere, but mitigation is challenging — in large part because there hasn’t been enough research on what can be done, finds a new report from the Government Accountability Office.

The report, released today, explained that there are “almost 5,500 active satellites in orbit as of spring 2022, and one estimate predicts the launch of an additional 58,000 by 2030.” Large constellations in low Earth orbit (LEO) “are the primary drivers of the increase,” the report said.

“Satellites provide important data and services, such as communications, internet access, Earth observation, and technologies like GPS that provide positioning, navigation, and timing. However, the launch, operation, and disposal of an increasing number of satellites could cause or increase several potential effects,” the report says.

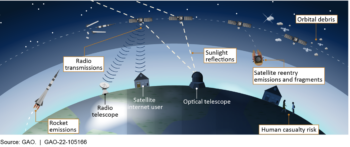

GAO studied three primary threats from that explosion of on-orbit activity: an increase in orbital debris; harmful emissions into the atmosphere from more launches; and the disruption of astronomy as satellites reflect sunlight or cause a cacophony of radio signals. And the congressional watchdog office suggested a number of policy options that US government policymakers could take to mitigate those risks, ranging from funding expanded research to increasing data sharing to setting new standards and regulations.

Of those three threats, the dangers of orbital debris are the most well understood — and the problem that the US and other governments have been most active in attempting to resolve.

The Government Accountability Office reviewed the potential hazards caused by the increase in large constellations of satellites.

“We need to address space debris so that space is sustainable and remains a working environment,” Ezinne Uzo-Okoro, assistant director for space policy at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), said today.

“We are looking to develop a risk framework to understand the amount of debris that would impact different stakeholders,” she told the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance (AMOS) conference in Maui.

That framework will be the result of the OSTP’s “National Orbital Debris Implementation Plan” [PDF] released in July, that set out 44 research tasks for US government agencies to help figure out how the government can better tackle the growth of dangerous space debris.

For example, Uzo-Okoro explained that the Defense Department be helping to build out the framework, using the findings and recommendations from efforts like the interagency Space Systems Anomalies and Failures (SCAF) workshops.

The SCAF workshops are held annually “to bring together civil, industry, academia, and military personnel who do not regularly interact with common interests in space system anomalies and failures including flight and ground system operators, space environment experts, spacecraft designers and mission assurance professionals,” according to NASA website. The next SCAF is slated for March 29 and 30 in Chantilly, Va., also where the National Reconnaissance Office is headquartered.

Further, Uzo-Okoro said, there is thought being given to potential changes to US policy for sharing data with commercial satellite operators about malfunctioning spacecraft that are drifting out of their normal orbits and could potentially crash into others in order to improve on-orbit safety.

The OSTP implementation plan also kicked off a government-wide review of whether government, civil and commercial operators should be exhorted, or required under federal agency licensing regulations, to de-orbit dead satellites earlier than the deadline of 25 years after end of life. That review of the US government’s Orbital Debris Mitigation Standards and Procedures is being led by NASA, with participation from the Pentagon and other agencies.

“We do need an updated review, because 25 years is too long,” Uzo-Okoro said.

Meanwhile, the independent Federal Communications Commission (FCC) today made a first move in that direction — deciding to require that satellite operators subject to its own regulations must de-orbit spacecraft stationed in LEO within five years after they cease to operate.

The FCC regulates the use of radio frequency spectrum, and thus most commercial satellite operators (and all commercial satellite communications operators) must get its approval before launch. The commission first proposed re-consideration of the 25-year rule back in April 2020, and on Sept. 8, it issued a draft ruling to set the disposal deadline at five years. Today’s action, made at the monthly FCC public meeting, made that deadline formal — although operators are being given a two-year window to make the shift.

“The new 5-year rule for deorbiting satellites will mean more accountability and less risk of costly collisions that increase debris,” the FCC said in a press release announcing the new order.

FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel stressed that the change was necessary to ensure the growing space economy.

“Our space economy is moving fast. The second space age is here. For it to continue to grow, we need to do more to clean up after ourselves so space innovation can continue to respond,” she said in a statement following the decision.