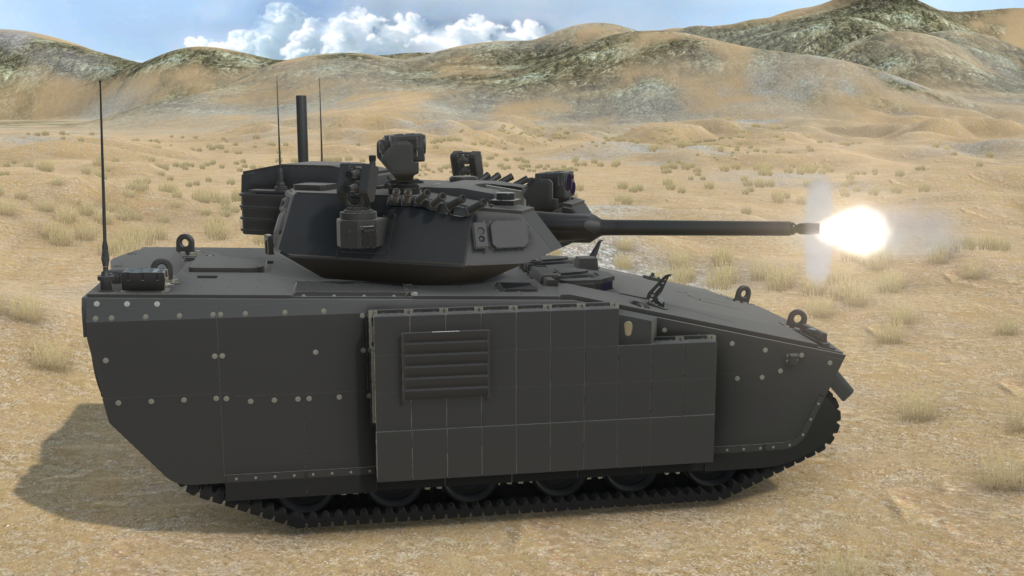

BAE’s design for the Army’s future Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) to replace M2 Bradley (BAE Systems graphic)

BAE’s design to replace its Reagan-era M2 Bradley troop carrier looks an awful lot like a sexed-up Bradley. But inside, the company told reporters today, the company’s proposal for the Army’s future Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) contract is radically different than its predecessor. For starters, you’d have a hard time finding the engine.

RELATED: Lighter, hybrid, & highly automated: the Army’s next-gen armor

Like the other four competitors for OMFV, the BAE machine will use a hybrid-electric engine instead of a traditional internal combustion engine. While other companies haven’t divulged details, at least not yet, BAE’s James Miller, VP for business development, told reporters this morning the BAE design uses a “serial” hybrid diesel-electric engine that’s “distributed” throughout the armored hull.

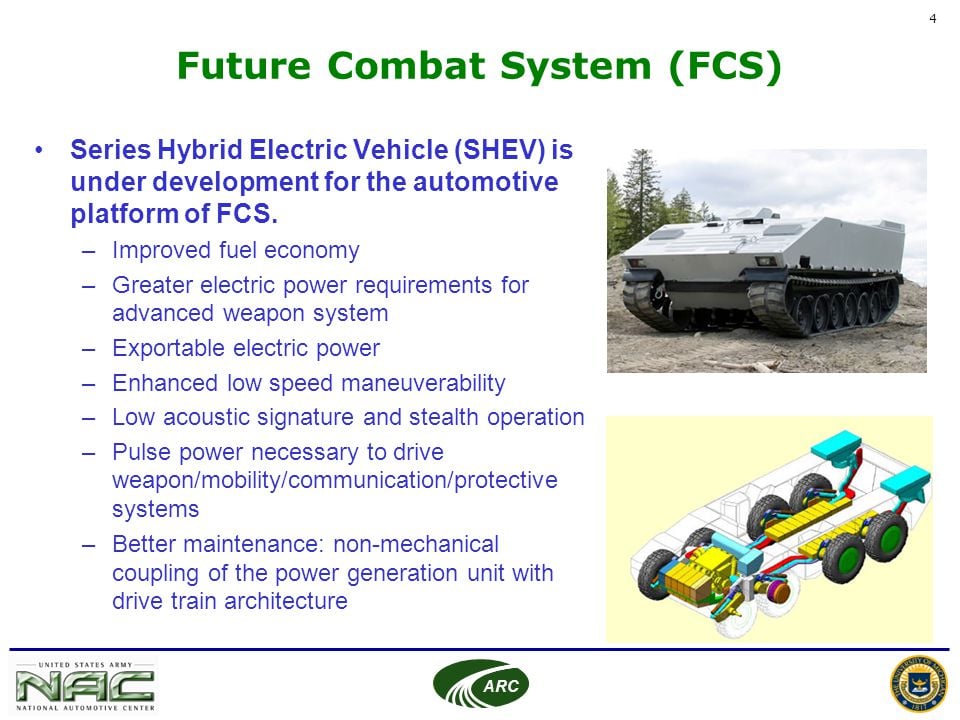

What does that mean? Traditional troop carriers (Armored Personnel Carriers, APCs, and Infantry Fighting Vehicles, IFVs) have a single big engine, at the front, where it makes a big heat signature on enemy infrared sensors and can be taken out by the first shot to penetrate the armor. But the BAE OMFV replaces the one big engine with a series of smaller hybrid-electric modules along either side of the hull. (BAE actually pioneered this approach in the Future Combat Systems vehicles cancelled back in 2009.)

An old Army slide shows the configuration of the hybrid-electric drive in the cancelled Future Combat Systems (FCS) vehicle.

The benefits? Despite producing a whopping 1,070 horsepower, the distributed drive spreads out its heat signature along both sides of the hull, making it harder for a heat-seeking enemy to find and track. It’s also designed to reduce noise, allowing the vehicle to power its electronics for nine hours with the engine off, known as “silent watch,” or drive 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) on batteries alone, with no engine noise.

It’s meant to reduce the risk of a single solid hit immobilizing the vehicle, what soldiers call a “mobility kill.” It also reduces weight — although the vehicle, with its modular armor plates configured for combat, is still 50 tons, considerably heavier than the Bradley. And finally, the distributed engine frees up space inside the hull, allowing the designers more freedom to relocate components, a lot like kids playing with Lego.

Mike Peck of General Dynamics shows the difference between the new 50 mm round the Army wants to use on future troop carriers and the 25 mm round on the current M2 Bradley.

In fact, the Lego philosophy of design, what engineers call Modular Open Systems Architecture (MOSA), is mandatory on the Army’s OMFV program, and BAE has embraced it enthusiastically, Miller said. This approach isn’t unique to BAE: Archrival General Dynamics has also emphasized MOSA and adaptability.

The idea is a design that’s easy to upgrade, with all software and hardware connecting to common interfaces defined by strict standards. That way the Army could easily swap out obsolescent systems, plug in all-new ones, or even reroute a function in mid-battle from a combat-damaged processor to a backup computer elsewhere in the vehicle, preventing a single lucky shot or breakdown from crippling, for example, fire control.

That adaptability contrasts starkly with Cold War-era vehicles like the Bradley, where every function was hardwired into a specific piece of hardware with its own proprietary software, making every upgrade a jigsaw-puzzle nightmare of complex systems integration.

The Bradley in particular is overtaxed on both weight and electrical power, with some units in Iraq, for instance, having to turn off one system, like a sensor, to free up power to run another, like a counter-IED jammer. Adding an Active Protection System to shoot down incoming anti-tank rockets and missiles has been particularly difficult, although the Bradley is gradually getting the same Israeli-made Iron Fist APS used on the new BAE design.

RELATED: Lynx Strikes Back: How Rheinmetall Could Win Army OMFV (ANALYSIS)

Those upgrade difficulties are a big part of why the Army — after four decades of modifying the Bradley — has decided to go with an all-new design for OMFV. They wanted a built-in APS instead of kludging one on, better protection against both top-attack missiles and roadside bombs (traditional armor is heaviest on the front), a bigger gun (a 50 mm MX913 autocannon vs. Bradley’s 25 mm), a lot of automation, and, most important, a lot of room to grow.

The initial “desired characteristics” were actually so broad, said Miller (with some exaggeration), “you could almost provide a pickup truck with a heavy weapon on it at one point.” At the other end of the scale, BAE’s initial proposal was a hulking brute, but their modular approach allowed them to rapidly redesign down to a more manageable 50 tons — still heavier than the most uparmored Bradley — when the Army made clear it wanted something else. Since then, all five competing designs have converged on a similar size and armament.

RELATED: OMFV race revs up: All 5 competitors bid to build Bradley replacement prototypes

BAE’s design for the Army’s future Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) to replace M2 Bradley (BAE Systems graphic)

“Our vehicle was much bigger than this when we started,” Miller said. “We thought the army would want a full squad,” i.e. nine fully-equipped infantry soldiers, in the passenger compartment. That’s what the Army had insisted on in two previous, cancelled attempts to replace the Bradley — Future Combat System and Ground Combat Vehicle — and on the successful 8×8 Stryker. But for OMFV, as the Army and five industry teams went back and forth over possible designs, the service decided it could go down from nine infantry passengers to six, and from a three-person crew to two.

That forces an unprecedented reliance on automation and artificial intelligence. “You can’t do a two man crew without a lot of AI support,” said Miller.

So the turret, designed by Israel-based Elbit and armed a Northrop Grumman 50 mm XM913 gun and a missile launcher, is unmanned — but it features an Army-developed targeting AI called ATLAS. The Advanced Targeting & Lethality Automated System doesn’t actually let an algorithm pull the trigger, which would violate Pentagon regulations on human control, but it can detect potential targets, highlight them on a screen, and bring the gun to bear with computerized precision at the human press of a button. The BAE design may also make use of another Army-developed AI system, the Robotic Technology Kernel, for cross-country navigation – i.e. a self-driving tank, which is what puts the “Optional” in Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle.

RELATED: Can the Army’s robotics programs build AI the Silicon Valley way?

But BAE and its corporate teammates will definitely have to develop their own software, not just download Army-issue algorithms and click “install.” One of BAE’s partners is QinetiQ, a UK-based company with extensive expertise in robotics and hybrid electric drive.

“We’ve completely replaced the old mechanical transmission system and gearbox with the new EX-Drive,” said Mike Sewart, QinetiQ’s group CTO, on this morning’s call. “What that essentially means is, irrespective of how the electrical power is supplied — so it could be supplied through a generator on a diesel engine, it could be supplied through a battery, it could be supplied on both, it could be supplied in future by a hydrogen fuel cell — it doesn’t matter… we can power the vehicle.”

Another partner is Curtiss-Wright, which boasts extensive experience in modular open-architecture design. “The requirements that came from OMFV represent a real paradigm shift of how we’re going to take open systems and really make it substantially impactful,” said Jacob Sealander, a senior architect at Curtiss-Wright. ““The Army has said MOSA’s a law. It’s not a suggestion.”

As a result, “the community can all develop to the same thing,” Sealander told reporters on the call. “There’s not any one [company] developing the solution. [It’s], ‘how do we develop in a way where we can bring all of these pieces together from a lot of different places that are using the same standards and approaches?’”

BAE is proud of its extensive experience on armored vehicles, said Miller, but “this is not the PIM program, this is not the AMPV program, this not the predecessors to those, where everybody saw BAE as a heavy metal bender…. The world is changing and it is really about integrating [the] software, the open architecture.”

For example, the Army doesn’t currently require a specific counter-drone capability on OMFV. But given how deadly drones have proven to armored vehicles in Ukraine — both as weapons in themselves and as spotters for artillery strikes — the Army might want to add that sooner than later. The BAE OMFV’s modular design would make that easy, Miller claimed.

Even if the service wanted to add, say, a high-powered laser weapon, Miller said the design can ramp up to provide 700 more kilowatts of electrical power than it currently does. (Miller declined to disclose the current figure, but it’s likely to be at least the 160 kW generated by an experimental hybrid-electric Bradley). By contrast, the Army’s still fielding a 60 kilowatt counter-drone laser on its own dedicated vehicle, a Stryker variant.

“IFVs [Infantry Fighting Vehicles] are in service for a long time, decades,” Miller said. “You have to start with a vehicle that can grow and adapt to new threats, new technologies.”

Army closing in on selecting new spy-plane integrator, user assessment around late-2026

HADES is “designed to support active campaigning short of conflict and then potentially support targeting in conflicted areas where you might let high-end stealthy fighters or unmanned systems take first contact,” said Andrew Evans, the ISR Task Force director.