Canada Sapphire satellite for monitoring space objects (Illustration: MDA)

WASHINGTON — Replacing Canada’s sole aging space tracking satellite is the top modernization priority for the military’s new space operations organization, according to its commander, Brig. Gen. Mike Adamson.

Improving space domain awareness is “from where I sit, the most important” of the 3 Canadian Space Division’s three major efforts to improve Canada’s space capabilities, he told Breaking Defense in an interview Friday — echoing the sentiments of his US counterpart, Space Command leader Gen. Jim Dickinson.

The space division was stood up in July as specialized command underneath the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). The goal, Adamson said, was to highlight that space, rather than a “novelty,” is central to future warfighting.

“It’s almost like it’s taken [space] out of sort of a back office … brought it forward and said, ‘You know, this is something that’s critically important to everything that we do. You know, we need to be paying attention to what’s going on in the domain. We need to invest in the domain ourselves. We need to be aligned with our allies in terms of what everyone’s doing,'” he said. “And it just adds that extra little bit of gravitas to the whole thing.”

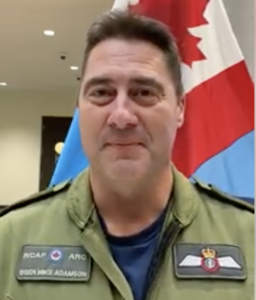

Brig. Gen. Mike Adamson. (US Space Force Facebook page)

He said the new force structure was in response to the 2017 Canadian defense policy’s statement that “protecting and defending the space domain” is a key role for the country’s military.

“It’s taken us a couple years to chew on that and sort of understand: ‘What does that mean, defending?'” he said. “Are we only concerned about Canadian Forces assets and mutual protection? Does it include our allies? As we blur the lines between commercial operators in that domain that are providing effects for national security, do we defend and protect them as well? And the answer would be yes.”

The policy document, called “Strong, Secure, Engaged,” also sent a message to the Canadian public and its allies that there is no “policy impediment” to the use of force by the military in undertaking the protect and defend mission.

“It also signaled that, in that effort, there was nothing that we weren’t willing to discuss in terms of capability — whether that be surveillance, reconnaissance, electronic warfare, space control — and it basically opened up the aperture” for the “domestic audience to understand that there are no policy impediments to what we might do,” he said.

While there are “certain things we probably won’t get into, like active kinetic weapons systems,” he added, there are systems with “reversible effects that we might be interested in.“

Modernization Priorities: Sapphire, RADARSAT, Arctic Satcom

Adamson noted that, like the US military’s SPACECOM, the 3 Space Division is an operational command and has no direct budget authority. (Acquisition is instead the bailiwick of the RCAF Air & Space Force Development office.)

“I am really operationally focused,” he said. “I am the Joint Force Space Component Commander. So basically, I am the guy responsible for delivering space effects to our warfighters at home and abroad.”

But also like SPACECOM, he has direct input into crafting the requirements for new capabilities to be developed with the some $14 billion CAD (about $10.4 billion USD) the government plans to invest in space capabilities over the next two decades. That investment, he said, is aimed at three key priorities: replacing Sapphire, developing a new constellation to replace the RADARSAT remote sensing satellites; and improving satellite communications in the Arctic.

Sapphire ‘Beyond End Of Life’

The Sapphire space domain awareness satellite was launched into low Earth orbit at about 773 kilometers in altitude in 2013. Prime contractor MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA) which integrated the satellite’s SSTL-150 bus produced by Surrey Satellite Technology and its optical payload produced by COM DEV International.

The Canadian defense department in 2020 announced a plan to replace Sapphire under a project called “Surveillance of Space 2” worth between $100 million and $249 million CAD (about $78 million to $193 million USD). That project “will consist of a ground based segment and an on-orbit segment,” Adamson said.

“Sapphire has done yeoman’s service for us. It is beyond end of life, but keeps chugging away like the Energizer Bunny. And, every day that it has a hiccup, I go, ‘Not today, not today,'” he said.

Further, Canada is the only US ally to own and operate a space surveillance satellite, Adamson noted, with Sapphire serving as a node in Space Command’s Space Surveillance Network of radar and telescopes for monitoring the heavens.

“I think that is a niche capability that we’re good to provide on,” he said. “I think by contributing that to the larger alliance efforts, it gives us so much access to so many other things, predominantly from the US, but also from from the UK and Australia,” he said.

RADARSAT Replacement Far Off

The Canadian government is planning to replace its three RADARSAT Earth observation satellites used by the military to monitor the country’s borders. (Screengrab from Canadian Space Agency video)

Canada’s military, in tandem with the Canadian Space Agency, operates three RADARSAT synthetic aperture radar satellites for remote sensing, also built by MDA.

“That’s a critical enabler for us. We we take that RADARSAT information and we overlay shipping AIS, Automatic Identification System, data and create really good maritime domain awareness,” Adamson explained. “So that’s an ongoing capability we want to keep going and we have a follow on project for that.”

The plan to replace the satellites, launched in 2019, is in its infancy and Adamson did not provide details.

Option Analysis For Arctic Satcom

Adamson said that developing a satellite communications capability is essential for command and control of Canadian forces in the High North. But whether that will involve the development of a military satellite, buying commercially made satellites, or simply buying satcom as a service remains unclear, he explained.

“We’re in options analysis at the moment, so we’re just trying to understand what that plan is. But that will be informed by what are probably some significant paradigm shifts in how we deliver effect for national security,” he said. “Once upon a time, it would have been a military-owned satellite doing its thing. That’s not necessarily off the table. But there are so many other options that are now available.”

HASC chair backs Air Force plan on space Guard units (Exclusive)

House Armed Services Chairman Mike Rogers tells Breaking Defense that Guard advocates should not “waste their time” lobbying against the move.