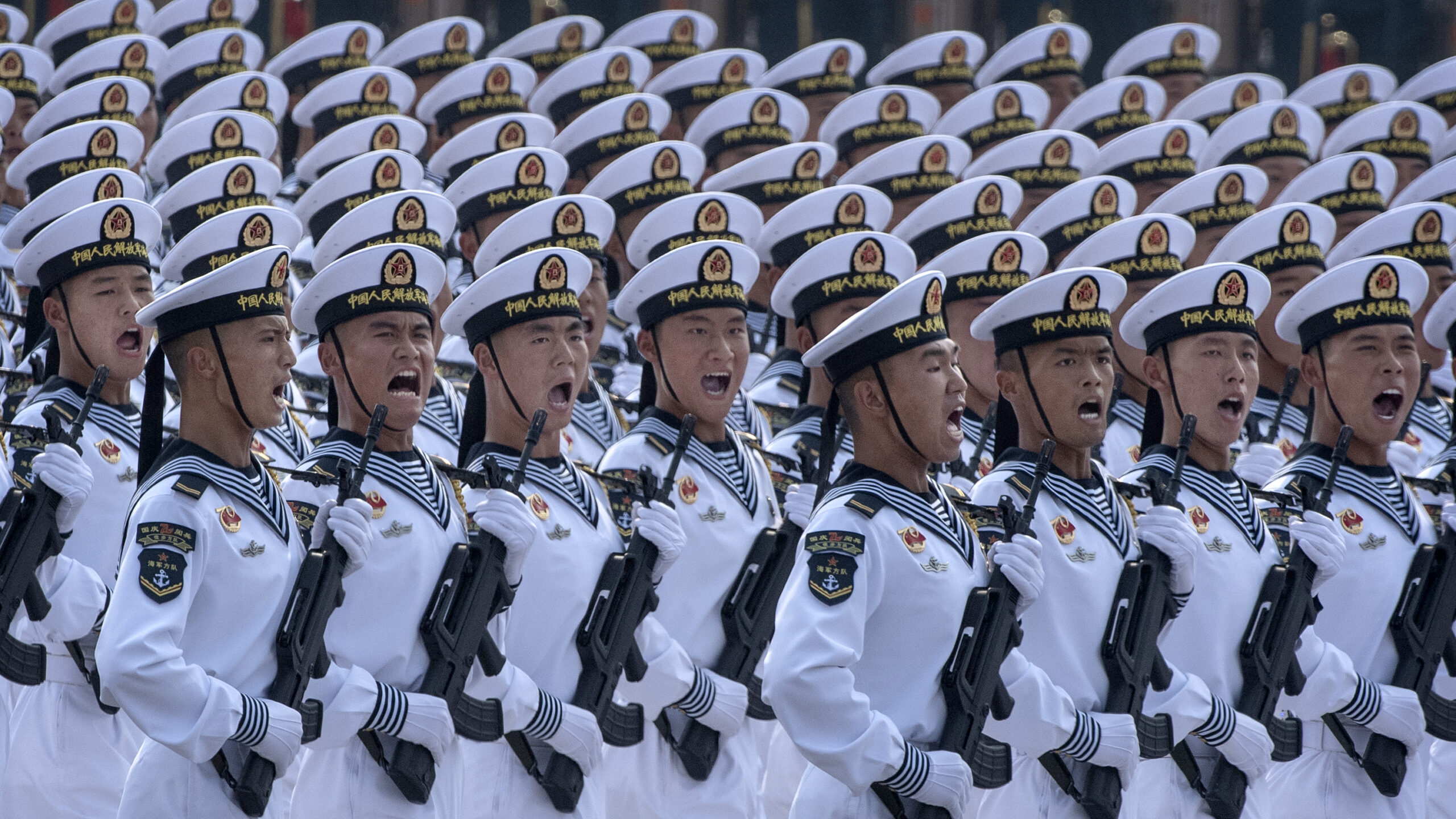

Chinese navy sailors march in formation during a parade to celebrate the 70th Anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China at Tiananmen Square in 1949, on October 1, 2019 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

Will China invade Taiwan and, if so, when?

Attempts to answer this question are clouding rather than clarifying America’s national security debate. It’s long past time for policymakers and military leaders to stop speculating about China’s timeline for war and focus on America’s timeline for deterring it.

Two years ago, Adm. Phil Davidson, then-commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, testified to Congress that China may be prepared to act on its ambitions to control Taiwan by 2027. This so-called “Davidson window” has now become a central topic of debate in US defense strategy toward China. It’s a debate that grew more intense last month when Gen. Mike Minihan, commander of the Air Force’s Air Mobility Command, warned in a memo to his command that war with China was probable by 2025.

Make no mistake: the Chinese Communist Party aims to control Taiwan. It is willing to use force if peaceful means fail. And it has accelerated its military modernization to make coercion or invasion feasible, even against a US intervention. In citing timelines like 2025 or 2027, military leaders and civilian policymakers are trying to break the strategic myopia — 20 years of treating China as an important but non-urgent challenge for the long term — which has left America’s military insufficiently prepared for the challenge at hand. Whatever one thinks of these assessments or their public discussion, their urgency is spot on.

But at this point, these predictive timelines are becoming counterproductive.

Specific dates — whether near or far — confuse the subject. Do they refer to China’s timeline to invade Taiwan, or just the PLA’s timeline to be prepared for such a scenario? What about other scenarios such as a “joint firepower strike” or blockade? The last two years of debate about the “Davidson window” shows the nuance is often lost.

RELATED: ‘A bloody mess’ with ‘terrible loss of life’: How a China-US conflict over Taiwan could play out

Predictive timelines mire policy debate in speculation. They perpetuate a false hope that we possess or can attain clear insight into China’s intentions, in highly contingent scenarios, years in advance. Debate centered on conjecture is ceaseless, so the debate on China’s timeline never ends. And in its wake, the debate on how America can best preserve its military advantage and deter war with Beijing struggles to begin.

Predictive timelines can unintentionally project a sense that war is inevitable, which undermines the pursuit of deterrence. The American people do not respond well to fatalism. They need to know that with their support for bold and determined action, we can succeed in preserving peace through deterrence.

Most importantly, predictive timelines oversimplify the Pentagon’s core challenge of balancing risk through the allocation of resources over time. Whether near or far, specific dates form the basis of arguments for mitigating risk in one timeframe at the expense of another. Some warn the risk of war is imminent, so we must shift resources to “fight tonight” readiness. Others say there is no imminent risk, so we can divest now to invest later. Neither will suffice: The speed, scope, and scale of China’s military buildup has increased the risk of war and distributed it over an extended timeline. The response of America and its allies has been too little, too slow, and too late. The result has been the erosion of conventional deterrence, which Admiral Davidson once called “the greatest danger for the United States.” Unfortunately, that danger is not limited to the “Davidson window,” but will persist deep into the Pacific century.

Whether China invades Taiwan in the next five years,the next 50, or never, American leaders must recognize we have entered an indefinite window of concern in which the possibility of war with China and the plausibility of American defeat are realities for both the present and the future. This reality collapses our decision space and confounds simple temporal trades between the near, medium, and long term. It means the Pentagon needs a cohesive strategy for mitigating risk not in one timeframe, but across all timeframes.

If not specific dates, how should we frame America’s approach to reducing the threat of war in the Indo-Pacific?

We need to stop trying to predict the future and start preparing for it. Deterrence will not come from divination. Instead, we must learn to decide, act, and invest in the face of uncertainty about China’s intentions. We need a policy and military mindset of sustained urgency.

The motto of the US Army’s 2nd Cavalry Regiment is “Toujours Prêt,” or “Always Ready.” During the Cold War, its readiness helped deter a Warsaw Pact invasion of Germany. Simultaneously, its modernization efforts enabled the regiment to dominate its Iraqi foes in the Gulf War. We need a similar mindset for deterring China: America’s military must be ready today and tomorrow.

We need significant and sustained growth in America’s defense budget to mitigate both near- and long-term risk. Bolstering allies and partners, acquisition reform, and new operational concepts are also necessary to mitigating risk across all timeframes. But too often, these approaches are framed as alternatives rather than complements to a higher defense budget. Real growth in defense spending is not a panacea, but paired with strategic prioritization, it is an essential component to mitigating the elevated and extended risk posed by China across all timeframes.

Most of all, we need to recognize that deterrence in all timeframes requires urgent decision, action, and investment. No matter what China’s timeline for war might be, America’s timeline for deterrence is right now.

In the near term, if we intend to improve the readiness of our forces, increase US presence in the Indo-Pacific, and expand munitions production, the time for investment is now.

In the medium term, if we intend to achieve joint all-domain command and control, build more distributed and resilient posture and logistics, and amass stockpiles of critical munitions, the time for investment is now.

In the long term, if we intend to reverse the shrinking size of American air and naval forces, modernize our conventional and nuclear forces simultaneously, and realize the full potential of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and autonomous weapons systems, the time for investment is now.

The longer we wait to summon the urgency, ambition, and imagination this moment requires, the longer the window of concern will be.

Will China invade Taiwan and, if so, when?

If the answer to that question is to be no, policymakers and military leaders must be honest with the American people. The near-term threat posed by China is real, it will change over time, and remain with us for years to come. Inaction will make it worse. But action now can ensure that deterrence holds, and peace prevails.

Dustin Walker is a Non-Resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was previously the lead adviser on the Indo-Pacific to the Senate Armed Services Committee and an adviser to Sen. John McCain.