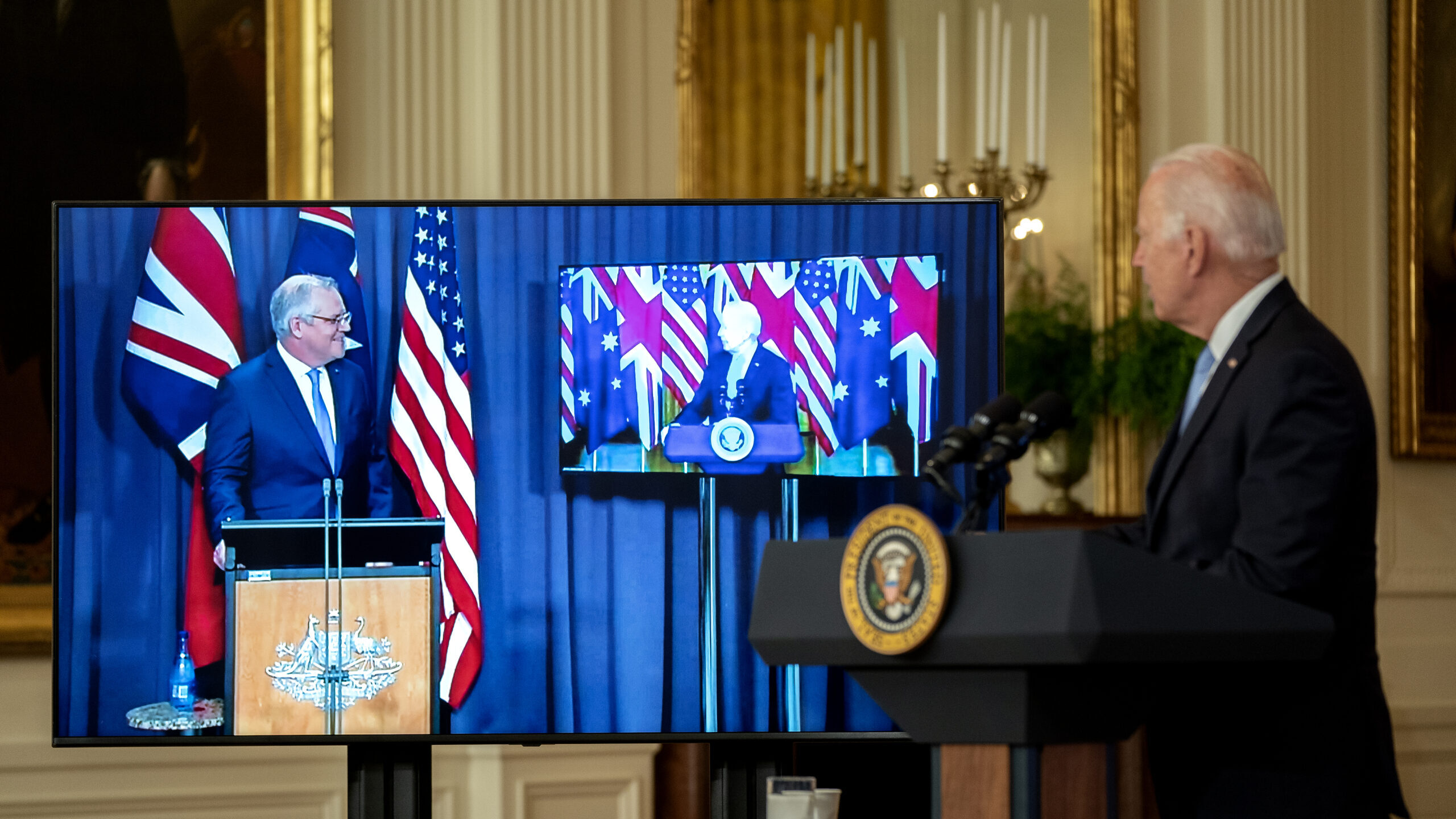

U.S. President Joe Biden listens as Scott Morrison, Australia’s prime minister, speaks via videoconference in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021. Australia is joining a new Indo-Pacific security partnership with the U.S. and U.K. that could pave the way for it to acquire nuclear-powered submarines, likely signaling the end of its deal with France to buy conventional craft. Photographer: Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In coming days President Joe Biden is expected to host a much-anticipated summit to announce how the United States and United Kingdom will provide nuclear-powered submarines to Australia – the centerpiece of the trilateral AUKUS partnership dramatically unveiled 18 months ago.

When first publicized in September 2021, the deal sounded like a win for all three countries. The United States would get Australia to buy submarines that effectively would come under US command. Australia would increase the likelihood of the United States defending it from China. And the United Kingdom would bolster its ship-building industry.

However, the current implementation plan, as confirmed recently by a senior Australian official, contains a fatal and unnecessary flaw: Australia’s submarines would be fueled by tons of nuclear weapons-grade, highly enriched uranium (HEU) – an amount sufficient for hundreds of nuclear weapons – setting a precedent that would foster nuclear proliferation.

President Biden can and should insist on a safer nuclear fuel that could preserve both AUKUS and nonproliferation.

Weapons-grade uranium is arguably the most dangerous substance on earth. Terrorists could make a Hiroshima-sized bomb from just 100 pounds of it. Using more advanced methods, a country could produce an equivalent explosion from only 20 pounds [PDF]. Yet, Australia would acquire up to 10,000 pounds of it [PDF] – in reactors for “at least eight nuclear-powered submarines” under AUKUS.

Because HEU is so dangerous, the United States has striven for half a century to eliminate its use globally, except in nuclear weapons, by converting domestic facilities to use safer, low-enriched uranium (LEU), and then persuading other countries to follow suit. Around the world, some 71 nuclear reactors and all major producers of medical isotopes have already switched to LEU. In 2018, the United States also declared that Army reactors would use LEU fuel, and in 2020 expanded that to NASA reactors [PDF].

The only US exception has been for Navy reactors in submarines and aircraft carriers, which still rely on HEU fuel. However, in a 2016 report to Congress [PDF], the Navy said that it too could probably switch to LEU fuel. Yet the Navy has failed to do so, dismissing proliferation concerns on grounds that the United States already has nuclear weapons.

That excuse clearly does not apply to Australia, a country that has pledged under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) never to acquire nuclear weapons.

The precedent of such a state acquiring tons of weapons-grade uranium could unravel the global nonproliferation regime, because other countries would demand the same right. If the United States refused to provide them bomb-grade fuel, they could construct their own uranium enrichment facilities to produce it for naval or other reactors, on grounds that Australia had sundered the decades-long international taboo against HEU fuel.

Several countries rang the alarm last summer at the United Nations’ NPT review conference. Indonesia warned that “HEU in the operational status of nuclear naval propulsion” would endanger “the global non-proliferation regime” [PDF]. China asserted that it “sets a dangerous precedent for the illegal transfer of weapons-grade nuclear materials from nuclear-weapon states to a non-nuclear-weapon state” [PDF]. Even close US allies — the Netherlands, Norway, and South Korea — admonished the AUKUS countries by reaffirming that, “Efforts to reduce stocks of HEU and to minimize and eventually eliminate the use of HEU are a form of permanent threat reduction.”

The good news is that nuclear submarines do not require – and Australia has not demanded – weapons-grade fuel. France and China use LEU fuel in their submarines even though they possess HEU for nuclear weapons. Even the United States has been researching LEU naval fuel since 2016 [PDF], which also could be applied to British submarines that depend on US reactor designs and fuel.

In Australia, the admiral who leads the AUKUS task force disclosed on national television last month, when asked if Australia wanted HEU or LEU, “We will accept the reactor they give us.” Since Australia cannot obtain its first nuclear submarine until “well into the 2040s,” according to the US Navy’s top admiral, there is still time for the United States to design that ship’s reactor for LEU fuel.

That means it is entirely up to Biden to determine whether the AUKUS submarines will undermine the international nonproliferation regime by needlessly using tons of weapons-grade uranium fuel, or instead will reinforce that regime by complying with the international norm against HEU.

The wrong decision would set a precedent that many countries could exploit to produce HEU ostensibly for reactor fuel but in fact for nuclear weapons. In that case, AUKUS would create many more problems than it possibly could solve.

Alan J. Kuperman is associate professor and coordinator of the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project (www.NPPP.org) at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin.