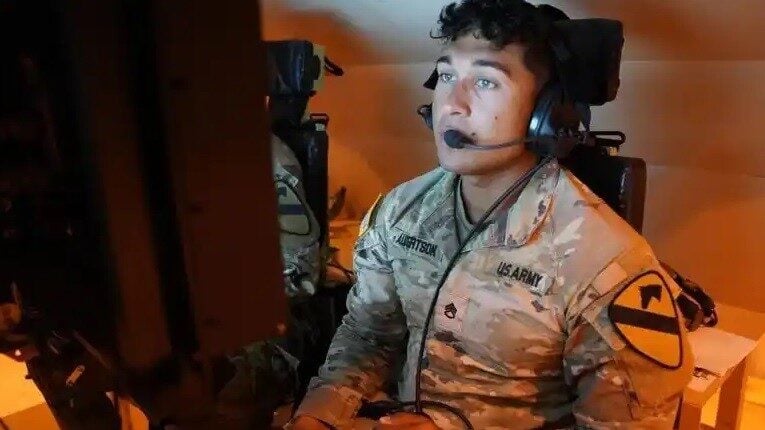

An Army soldier remote-controls an experimental Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV) Medium during field tests at Fort Cavazos (then Hood) in July, 2022. (Eric Franklin/US Army)

AUSA 2023 — “Keep It Simple, Stupid.” It’s an age-old military maxim, but KISS still applies even to the dawning age of high-tech combat robots. As the Army puts experimental Robotic Combat Vehicles through field tests in anticipation of a contract award in 2024 and a First Unit Equipped in 2028, young soldiers are providing vital feedback on how to streamline awkward interfaces and complex controls to a robust system they might actually trust their lives to in combat.

To take one very tangible example, “we’ve tried a number of different controllers and gotten really great feedback … that was a little surprising,” said Brig. Gen. Geoffrey Norman, director of the Next Generation Combat Vehicles team at Army Futures Command, during a Warriors’ Corner panel at the Association of the United States Army conference. “Really elegant Formula 1-style controllers … were actually less popular than a simple laptop-keyboard-mouse set up that the gamers might be more familiar with.”

Some of that feedback from an experiment at the Army’s National Training Center at Fort Irwin, Calif., recalled Michael Cadieux, director of the Ground Vehicle Systems Center at Combat Capabilities Development Command: “The operator at NTC [National Training Center] said, ‘you know what, I don’t need this kind of steering wheel that looks like an F1 steering wheel. [Just] give me a mouse and a keyboard, because I have like 29 hours of War Thunder every day, and I can absolutely control multiple robots and their payloads from a mouse and a keyboard.’”

“A lot of our young people are digital natives and are very comfortable employing this type of technology,” said Maj. Gen. Curtis Buzzard, head of the armor and infantry “schoolhouse” at Fort Moore (formally, the Maneuver Center of Excellence). That means they may be less vulnerable to information overload than their elders, he explained: “Cognitive overload — sometimes I think we may be overemphasizing that with young people because, again they’re using to doing things and watching multiple things at a time.”

At Fort Moore, Buzzard noted, “we run the small UAS [Unmanned Aerial System] master-trainer course, and we’ve got to go through and train folks on a bunch of legal requirements” — for example, safe operation in domestic airspace — “but we know a young person can grab a UAS and fly it within an hour.”

Robust, easy-to-use controls — like those popularized for gamers and hobbyists — have become a major focus for the Army, Buzzard said. That requires settling on standardized handled devices and software interfaces across a whole future fleet of unmanned systems. That will include multiple types of aerial drones and ground robots, equipped with a wide range of possible payloads, from machine guns and Javelin missiles, to long-range sensors or medical supplies, and operating alongside humans as part of multiple different units, from heavy armored brigades to light infantry.

“What we don’t want,” Buzzard said, “[is] we’ve got five different things we want to employ, so we’ve got to carry five different controllers and five different batteries that require five different types of training.”

“The key thing,” added Norman, “is regardless of what the physical construct is, that the software that’s running behind them is common and that the interface allows the soldier to go from one platform to another to another to another without having to learn a new software system.”

RELATED: Pentagon officials, industry leaders lay out 3 secrets for speedier software

The foundation of that hoped-for future commonality is a set of software standards known as GCIA, intended to apply across the Army’s entire future ground force of manned and unmanned vehicles. (It’s a nested acronym for GCS (Ground Combat System) Common Infrastructure Architecture). GCIA compliance is mandatory not only for companies working on RCV but for those competing to build the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, the replacement for the M2 Bradley troop carrier.

GCIA, in turn, is an Army ground force implementation of a wider philosophy called Modular Open Systems Architecture, which aims to establish a strict baseline of technical standards but then allow plugging in a wide variety of software packages, or modules, from any company, as long as the software complies with the standard. The hope is this can break the all too common “vendor lock” monopolies, where one large prime contractor develops bespoke software that only it can modify for the rest of a system’s service life.

“The intent there is to have an open system, where we are able to partner … with industry, best of breed athletes, that understand how to bring very unique and capable software modules into the platform,” said Cadieux. “[There are] probably greater than 50 different industry partners we’ve been collaborating with.”

Another way the Army is trying to get simpler, more flexible and more compatible systems is to separate software development from the work on the various unmanned vehicles. The Robotic Combat Vehicle Light, for instance, is “actually two programs,” explained Norman: “a platform program to develop the robotic vehicle itself” — with four companies competing — and “a Software Acquisition Pathway [for] modular system architecture.”

That kind of split is increasingly seen as a more flexible alternative to old-school megacontracts in which one traditional prime contractor does everything. The Pentagon has historically struggled to manage information technology programs — a problem that it’s intent to overcome in an era of warfare where software, not hardware, becomes ever more decisive.