Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Ukraine’s Defence Minister Rustem Umerov speak at the 15th meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, Sept. 19, 2023 (DoD photo by Chad J. McNeeley)

When Congress narrowly avoided a government shutdown, it did so by kicking the can down the road on continued aid for Ukraine. But what is actually in that aid? In this new analysis, Mark Cancian of the Center for Strategic and International Studies breaks down the numbers and reveals that less than half the money is going overseas, with the majority instead being spent in America itself.

“Aid to Ukraine” has become a sticking point in congressional budget negotiations, but the term is a misnomer. Much of the money supports US activities, and much of the money directly supporting Ukraine is spent not abroad, but here in the United States.

Although there are legitimate questions about the aid’s purpose and the war’s outcome, a blanket termination of the funding — as is now set without further Congressional action — would have unexpected and adverse consequences, such as leaving US forces in Eastern Europe unfunded and undermining global humanitarian relief. Although Congress has punted the final budget decision to mid-November, it needs to resolve the Ukrainian aid question now before previously appropriated funds run out.

CSIS has tracked aid to Ukraine from the beginning of the conflict, publishing analyses in May 2022 (“What Does $40 Billion in Aid to Ukraine Buy?”), November 2022 (“Aid to Ukraine Explained in Six Charts”), February 2023 (“What’s the Future of Aid to Ukraine?”), and, most recently, this August (“Aid to Ukraine: The Administration Asks for Money and Faces Political Battles Ahead”). These analyses have divided the aid into six categories: support of US military forces, shipment of US equipment to Ukraine, weapons procurement and services for the Ukrainian armed forces, humanitarian relief, economic support to the Ukrainian government, and US government agencies.

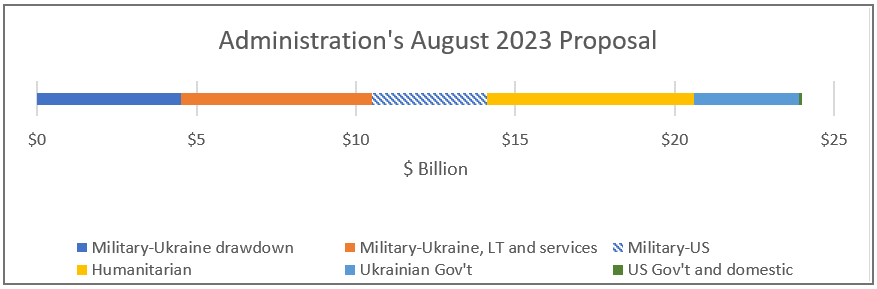

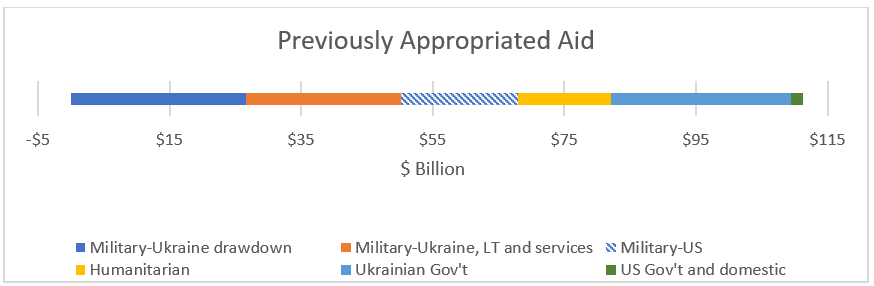

The charts below show how the money is distributed for the $24 billion supplemental that the administration has proposed and for the $113 billion that Congress has previously appropriated.

It is worth walking through the six aid categories to understand what is there, what it does, and what would happen if the funds disappeared.

Support of US military forces. At the beginning of the war, the United States sent forces to Eastern Europe to reassure the allies about US commitment and enhance deterrence in case the Russians thought about moving beyond Ukraine. Those forces peaked at about 20,000 personnel, but have declined over time to a current level of about 10,000. Units rotate about every six months. The aid packages include funds for the additional costs of these deployments, such as transportation, billeting, and a small amount for personnel benefits. The packages also include enhanced cyber defenses and increased intelligence operations in Europe.

Although the threat has diminished as Russian military capabilities have declined, it has not disappeared. Eastern European NATO allies would see withdrawal as reneging on NATO commitments. Even without additional funding, the administration would likely continue these efforts, meaning that DoD would take funds from other activities — weakening US global capabilities, particularly deterrence of China. The DoD Comptroller has stated, “I want to be clear, the department does not support that approach, which will create unacceptable risk to us.”

Some strategists have suggested withdrawing the forces and telling the Europeans that Ukraine is their problem, but such a move contravenes decades of bipartisan US foreign policy. If the United States wants to adopt such a strategy, it should do so deliberately, as a result of a strategic review, and not as the byproduct of a congressional budget impasse.

Funding for US government agencies. Although DoD and the Department of State have had the leading roles, US support for Ukraine has been a whole of government effort. For example, the Treasury Department has received money to enforce the extensive sanctions regime that the United States has imposed on Russia. In the current proposal, the Department of Energy would receive $66 million to prevent nuclear smuggling and prepare for possible radiological incidents, such as damage to the often-threatened nuclear reactors at Zaporizhzhia.

Like the support for US military forces, this money relates to Ukraine but does not go to Kyiv and benefits American interests broadly.

Humanitarian assistance. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has produced 6.2 million refugees globally and disrupted the global food supply. Help for refugees flows through USAID and then to many relief NGOs. Food relief goes through various Department of Agriculture programs. A significant amount of money helps settle Ukrainian refugees who have come to the United States.

These needs will not go away when the fighting ends. It will likely take years for all the refugees to go home and for the economic disruptions of war to dissipate.

Provision of US military equipment. Every two weeks or so, DoD announces another package of munitions and equipment that it is sending to Ukraine. This equipment comes from US stocks and, therefore, arrives relatively quickly; Most weapons arrive within a few weeks, though some take longer because of the training and logistics involved.

The budget mechanism is complicated. Congress has authorized billions of dollars of presidential drawdown authority (PDA) (22 USC 2318) allowing the president to send equipment to Ukraine. Previously, such aid was limited to $100 million a year and consisted mainly of older items sent to allies and partners with underdeveloped militaries. The war in Ukraine constituted a change whereby the United States has provided billions of dollars of such aid to a sophisticated military.

This aid runs about $1.4 billion monthly and is critical for maintaining Ukrainian resistance. Militaries in combat need a continuous flow of weapons, munitions, and supplies to replace those destroyed or used up in operations. Without this flow, resistance would weaken almost immediately and collapse within a few weeks as the pipeline of previously authorized items dried up.

The statutory authority does not require that the items be replaced, since that was not an issue in the past when most of the items provided were obsolescent and on their way out of the US inventory. However, replacement is militarily and politically necessary in the current circumstances because the United States is providing top-of-the-line equipment in large quantities.

An accounting change in early summer gave DoD $6.2 billion more PDA authority for transfers to Ukraine. However, according to the DoD Comptroller, there is only $1.6 billion, or just one month’s worth, of money for the US to backfill the weapons it is sending out.

Weapons and services to the Ukraine military. This flows through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI), a transfer account that moves money into other budget accounts for execution. A large part of the funding allows Ukraine to sign contracts with the US defense industry to buy weapons and munitions, for example, HIMARS and Javelins. Because these items must be manufactured, they will not arrive in Ukraine for two to three years and will likely be used for rebuilding the Ukrainian military postwar.

The USAI also funds logistic support, salaries and stipends for Ukraine’s military, the purchase of foreign equipment, and intelligence support to Ukraine. These have immediate battlefield impact, and funds are nearly gone, with only $600 million left. This will last about two weeks, although DoD could stretch it out to a month by focusing on near-term needs.

Economic support to the Ukrainian government. This is “aid to Ukraine” in the purest sense. The war has disrupted the ability of the Ukrainian government to collect taxes and, thereby, its ability to provide regular government services. Outside funds replace these lost tax revenues. The argument for doing so is that it prevents social disintegration in Ukraine and, by maintaining a minimum level of services, allows workers and military personnel to focus on the war, not the survival of their families. Congress has enacted $27.3 billion of such support, and the administration says that most of this has been committed. The $24 billion aid package now being considered contains $3.4 billion for this purpose. The United States, like many countries, flows the funds through the World Bank.

This is one area where the Europeans and other global partners have exceeded the United States. Collectively, they have provided $111 billion, according to the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine tracker.

Most Ukraine ‘Aid’ Spent in the United States

As the discussion above shows, a large part of the aid is spent in the United States. Funding of US agencies, most of the funding for US military forces, most of the military equipment backfill and Ukrainian equipment purchases, and a part of the humanitarian assistance stay in the United States.

In all, about $68 billion of the $113 billion enacted (60 percent) would be spent in the United States, benefiting the armed forces and US industry.

This question of where money is spent also explains why some sources for “aid to Ukraine” spending cite $60 billion or $70 billion while others, like this analysis, cite $113 billion. The smaller number comes from the Kiel institute, which only includes funds committed and destined for Ukraine. Thus, it excludes money that has been appropriated but not yet committed to use. It also excludes money that is not spent in Ukraine. The $113 billion total includes everything. The former number might be described as “aid to Ukraine,” the latter number as “US efforts as a result of the war in Ukraine.”

Diverse Elements Of Aid Imply Opportunity For Choices

Some aid items are only tangentially related to the war in Ukraine. The Office of Management and Budget calls this the “Christmas tree” problem: Supplemental appropriations look like “free money,” and advocates try to attach funding for their programs to these bills. Thus, past appropriations of Ukrainian aid have included money for rare earth mining, development of advanced nuclear reactors, and modernizing the strategic petroleum reserve.

The administration’s proposed $24 billion aid package includes $1 billion for “transformative, quality, and sustainable infrastructure projects that … would allow the United States to provide credible, reliable alternatives to out-compete China.” The World Bank would receive $1 billion “to support the [International Development Association] crisis response window, which provides rapid financing and grants to the poorest countries to respond to severe crises” and another $1.25 billion through the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development for loan guarantees “to provide financing to help countries such as Colombia, Peru, Jordan, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Nigeria, Kenya, and Vietnam build new infrastructure and supply chains.” Finally, the package requests $200 million “to counter destabilizing activities of Vagner and other Russian malign actors in African countries.”

While these might be worthwhile activities, they are unrelated to the war in Ukraine. Congressional members concerned about the amount of spending for Ukraine might started here in their review.

As the above indicates, “aid to Ukraine” covers many different activities, so Congress could make distinctions rather than following an “all or nothing” approach. For example, Congress could drop unrelated items and put those through the regular appropriations process. Congress could focus on near-term requirements and defer longer-term requirements to future budgets. Congress could increase oversight to assure itself and the American people that the funds are spent appropriately. Above all, if members have concerns about aid, Congress could hold hearings on the individual elements of aid. This would also respond to criticisms of Congress giving a “blank check to Ukraine.

But above all else, Congress needs to do something to keep faith with Ukraine, which has sacrificed thousands of its citizens and dozens of its villages on the expectation that the United States would support its fight against aggression. Inaction would be irresponsible, given the many detrimental effects that an abrupt cessation would cause. The American people expect Congress to make decisions and not govern by inaction.

Mark Cancian, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, is a retired Marine colonel now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

France, Germany ink deal on way ahead for ‘completely new’ future European tank

Defense ministers from both countries hailed progress on industrial workshare for a project that they say “will be a real technological breakthrough in ground combat systems.”