GROTON, Conn. (October 14, 2023) – Sailors assigned to the Virginia-class fast attack submarine USS Hyman G. Rickover (SSN 795) man the ship during a commissioning ceremony at Naval Submarine Base New London in Groton, Connecticut (US Navy photo by John Narewski)

Congress is in the midst of debating whether to support President Joe Biden’s $105 billion supplemental request. While the pot of money is primarily billed as funding for Ukraine and Israel, it also included $3.4 billion specifically to help America’s shipbuilding. In this new analysis, Mackenzie Eaglen of the American Enterprise Institute lays out the reason why the Biden administration is worried about the fleet, and why she believes Congress needs to take action.

The White House’s $105 billion emergency spending request for ongoing wars in Europe and the Middle East also includes $3.4 billion for America’s submarine industrial base. This is on top of the $647 million in the president’s budget request for this fiscal year for submarine shipbuilding and workforce development.

The administration is in a hurry to strengthen the workforces and shipyards that build American subs. This is in part because the AUKUS alliance is important to bolstering deterrence in Asia. But some in Congress are concerned about the viability of supplying Australia with US-made attack submarines if our own sub fleet must shrink in the near term as a result.

This $3.4 billion supplemental is the latest in a string of proposed investment efforts to revitalize the ailing submarine industrial base, which includes the Biden administration’s previous $2.4 billion five-year investment and a potential $3 billion investment from Australia. While these are much-needed pools of money to reverse the decline of our submarine industrial base, the base needs to improve, not just recover, to build the submarine fleet required by our future navy, meet the commitments set forth in the AUKUS agreement, and continue to deter the aggression of our adversaries.

The president and Congress must go beyond one-off supplemental measures and provide our Navy with robust and stable budgetary investments for the critical years to come.

America’s Ailing Submarine Fleet

As initially laid out in the Biden administration’s FY22 shipbuilding plan, the Navy has set a requirement of 66 to 72 nuclear-powered attack submarines to adequately carry out the National Defense Strategy and deter and defeat adversaries. However, the US currently has a fleet of just 49 attack submarines currently — and the reality is bleaker when you look at actual operational rates.

In 2013, 12 submarines (23 percent of the total submarine fleet) were in maintenance or awaiting maintenance. A decade later, while the number of boats has gone up, the maintenance situation has actually worsened, and 18 submarines — or 37 percent — are not operational. This maintenance backlog shrinks down our 49-boat fleet to just 31 operational boats at any given time, half of what is requested by combatant commanders.

What’s causing maintenance delays? The problems are numerous, ranging from supply chain disruptions to faulty planning assumptions. Shortages of spare parts are forcing crews to cannibalize parts from other depot-laden vessels, exacerbating the logjam. However, the paramount obstacle is that there are only a half dozen shipyards in the entire country that can perform depot-level maintenance on nuclear-powered vessels, which is split between submarines and aircraft carriers.

With only so many berths available, there’s a long and growing waiting list for repairs. This is leading to a rapid shrinking of our attack submarine fleet. Take for example the USS Connecticut, which was damaged in an accident in 2021 and now isn’t expected to be operational again until 2026. The vessel has effectively been knocked out for a half decade.

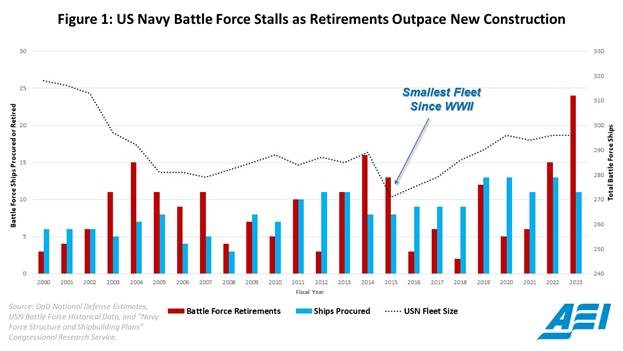

These issues shouldn’t come as a surprise since they are symptoms of deliberate policy choices. Since the end of the Cold War, the US Navy has been consistently downsized. Vast sums of ships were retired, and the total fleet size has been nearly halved from a 526 ship navy in 1991 to a 291 ship navy today.

The decline of our submarine industrial base is a particularly illustrative example. Under the budgets of President Ronald Reagan, the US Navy procured four attack submarines per year, and shipyard output matched demand. Contrast that with the post-Cold War drawdown, when stunningly, only three submarines in total were procured between 1991 and 1998.

Since the Pentagon is the sole buyer of warships, private industry responded accordingly to a plummeting of demand by cutting workforces and closing yards.

As seen in Figure 1, battle force retirements have outpaced new procurement for the past two decades. Unstable funding and changing demands have left industry to err on the side of caution in keeping excess shipbuilding capacity on hand. As former Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. Mike Gilday put it, “The biggest barrier to adding more ships to the Navy is industrial base capacity.”

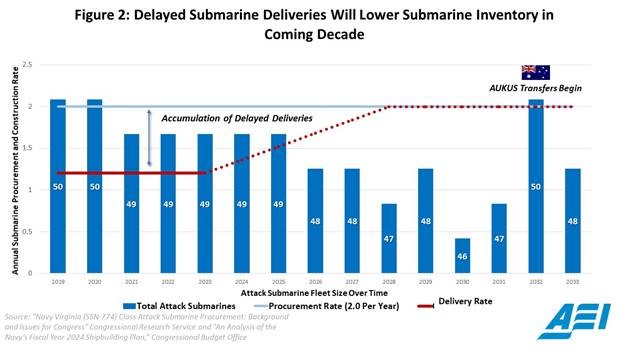

Owing to this shrunken industrial base, production of Virginia-class submarines is far behind schedule. The submarines are being procured at a rate of two per year. But production can’t keep pace with procurement, and on average only 1.2 submarines are being constructed annually. As retirements of older attack submarines grow in the coming decade, this bathtub in production not only means the Navy will be nowhere near stated goals, but also means that the US submarine fleet will plunge below necessary levels.

Worse yet, production of Columbia-class submarines has struck similar construction delays, and will likely pull time, space and workers away from Virginia construction.

Current Investment Proposals Are Not Enough to Reverse Decline

The Biden administration’s previously pledged $2.4 billion investment (which includes the previously mentioned $647 million in 2024) is spread over a five-year period. During that same time, the Navy is set to spend $83.7 billion in total submarine construction, including Columbia. Combined with the newly proposed $3.4 billion supplemental to be spent in FY24, the Biden administration’s total investment will amount to just a 6.9 percent increase over Navy plans over the next five years — enough to address some issues, but not nearly enough to double production. The extent of Australia’s additional AUKUS investment is also currently still being planned, meaning it’s far too early to ascertain which areas of the submarine industrial base it will boost.

Even with the prospect of these combined billions in additional investment, the Navy does not project attack submarine construction to rise to 2.0 subs per year until 2028. Navy officials have stated that Virginia class submarines have averaged an annual construction rate of 1.2 over the past five years, despite consistent procurement of two-subs-per-year. These construction delays mean that the Navy is set to endure at least a decade of delayed deliveries of attack submarines.

Considering that attack submarines have an estimated minimum 60-month construction timeline, delays in construction will dampen delivery rate far into the future even though the projected return to a 2.0 delivery rate in 2028 appears to mend the construction-delivery gap.

Years of procurement outpacing actual deliveries has resulted the accumulation of missed subs between 2019 and 2029. Based on the Navy’s current and past construction rate of 1.2 submarines per year and a projected linear recovery between 2023 and 2028 in the annual submarine construction rate, the Navy accumulates at least 5.6 submarines worth of “missed” deliveries over the decade, as depicted in Figure 2.

The consequences from operating well under planned delivery rates will have a delayed effect on the size of America’s sub fleet, as planned retirements for the older Los Angeles and Seawolf classes begin to accelerate in the late 2020s and early 2030s. Since these retirements are set to outpace new deliveries of Virginia-class subs, the fleet will shrink before it gets any bigger.

Under these current projections, the Navy will continue fall far short of planned ship levels in the least ambitious shipbuilding plan, which is based off of the President’s 2024 budget request and assumes no real growth in shipbuilding funding. Over the next decade, the Navy’s submarine inventory will peak at 50 attack submarines, well below the desired goal of 66 to 72 subs. As seen in Figure 2, the attack submarine fleet is set to plunge down to just 46 ships in 2030.

The actual fleet (versus the planned and projected fleet) is at least 20 boats short of the Navy’s requirements. This shortfall will undermine the strength of American deterrence. Nuclear-powered attack submarines are a key component in halting aggressive Chinese military action in the Indo-Pacific. A fleet of just 46 ships would mean our attack submarine fleet is set to be the smallest it’s been since the end of the Cold War in the late 2020s and early 2030s — precisely the window of maximum danger.

A shrinking submarine fleet could doom AUKUS, as the Navy won’t be able to manage the gap in capability due to the transfer of attack submarines to Australia. Research from the Congressional Budget Office indicates that the transfer of three to five Virginia-class submarines to Australia would have a lasting effect on the size of the US fleet. These CBO projections indicate that under current construction rates, the US fleet would not recover for this transfer until 2055 at the earliest.

More Capital for Capital Assets

What can be done? To mitigate this risk and meet both US needs and AUKUS commitments, sub production needs to double to a rate of at least 2.33 Virginias each year. This does not include additional production capacity needed for building Columbia-class submarines either, which is roughly two-and-a-half times the tonnage of a Virginia class.

Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., has been leading an effort in Congress for extra funds and authorities to meet expand sub construction to ensure AUKUS succeeds. The $3.4 billion in the latest supplemental spending request is a good start but there is more work to do.

These issues facing the Navy’s future submarine fleet are just the tip of the iceberg, as the surface fleet faces similarly stark and negative trends. Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, which account for 65 percent of the surface fleet, are reaching the end of their 35-year service lives. Already the Navy has begun to issue extensions to arrest the decline. A 2021 report directed by Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., found that there are numerous shortcomings in the surface fleet maintenance program, leading to cancellations, delays and reduced maintenance availability.

To make matters worse, China has surpassed our shipbuilding capacity, with a recent Navy report suggesting that China has over 200 times greater shipbuilding capacity than the United States. The report estimates that China’s shipyards have a capacity of 23,250,000 gross tons, while the United States has less than 100,000.

While the US Navy’s ship retirements often outpace new construction, China’s fleet has grown consistently with dozens of new hulls put in the water year after year. Future projections are bleak, as the US battle force is set to slowly climb to just above 300 ships by 2035, while the Chinese navy will stand at 475 battle force ships.

To adequately deter China and ensure the future strength of our fleet, Congress must provide the Navy’s shipbuilding budget with real growth to fully invest in facilities and workers. Defense budgets over the past few years have failed to offset rampant inflation.

The first order of business should be modernizing aging shipyards. Many key facilities were built for WWII and have not been overhauled to support the maintenance of nuclear-powered vessels. This has led to numerous challenges that contribute to thousands of days of maintenance delays.

Improving dry dock availability by building new dry docks and modernizing existing facilities is also urgent. The Navy has recently begun this work at existing yards which will expand topline maintenance capacity. But a portion of dry docks at shipyards are so antiquated that they cannot service modern aircraft carriers and submarines, worsening maintenance bottlenecks. To maximize more efficient repair timelines, these projects need funds now since modernizing dry docks could take 20 years to complete.

New shipyards and facilities should also be investigated. A recent report from the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States proposed the creation of a third shipyard dedicated to the production of nuclear powered vessels — especially submarines. Reopening a previously closed public shipyard, such as at Charleston or Mare Island, and reconstituting maintenance facilities in Guam would be a boon to submarine readiness.

The Congressional Budget Office has reported that shipbuilding budgets cannot afford the fleet of the future, and estimate at least a 23 percent increase to make even the least ambitious shipbuilding plan a reality. Congress has acted to ensure over the past two decades that the Navy’s shipbuilding budget has nearly tripled with legislators consistently appropriating more for ships than requested.

Congress must continue to work with the Navy to ensure the effectiveness of targeted investments in shipbuilding capacity. The pending supplemental bill to authorize additional procurement, fund shipyard modernization and train new workers are important to reversing the sub fleet’s decline.

Actions like these will equip our shipbuilders with the tools they need to staff up and open the yards, as well as send a strong signal to adversaries that we’re serious about size of our future fleet. Also, to ensure AUKUS is a win for all parties, Congress should approve additional funds immediately for the sub industrial base.

Mackenzie Eaglen is a defense expert at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors.