The Pentagon is increasingly reliant on a hodgepodge of code to make its systems work. (Pentagon graphic by Breaking Defense; computer code image by Sabrina Gelbart via Pexels)

WASHINGTON — American troops are famous for initiative, ingenuity, and improvisation; less so for following protocol. An old joke, usually ascribed to the Soviets, is that Americans are hard to fight because they don’t read their own field manuals or follow their own doctrine.

That kind of culture adapts quickly in a crisis, but, over time, it makes for a messy accumulation of ad hoc fixes that don’t necessarily work well with each other — or, sometimes, don’t work at all once a lone-wolf innovator has moved on. And in the era of increasingly complex computing, that problem is bigger than ever, according to the Defense Department’s top AI official.

“Some E-5 [i.e. sergeant] creates a solution in a hackathon, you deploy it and a war happens; that E-5 moves somewhere else: Who fixes it in the night when it’s broken?” the Pentagon’s Chief Digital & AI Officer, CDAO Craig Martell, said to a CDAO-sponsored conference Monday.

His goal: to tame that wilderness of brilliant one-off kludges and create a carefully cultivated garden of compatible, sustainable systems. Or, as he put it, “We’re trying really hard to strike this balance between fight tonight and the long term getting it right.”

“I have this battle within the org[anization] and I have this fight within the department,” said Martell, who came to the Pentagon from rideshare giant Lyft. “There’s a large faction that wants to focus only on the fight tonight and I totally understand that.”

But under the current system, or lack thereof, “right now, if they see a problem they want to fix, it’s either slightly unkosher and hacked together, or it can’t be done,” Martell said. “We want to make it as easy as possible for those closest to the problem to find the data, have the tools, have the policies, have the options, have the authorization to be able to quickly build a solution, [then] quickly get approval to operate and quickly deploy it in a sustainable way. That’s really hard.”

This broad-brush vision has some specific and significant consequences for bureaucrats and contractors, Martell made clear. That’s particularly true when it comes to managing the military’s seething sea of incompatible databases and, ultimately, building AI-powered Joint All Domain Command & Control (JADC2).

“if we only cared about the fight tonight, data quality isn’t that important,” Martell told the CDAO conference. “We could actually just contract out a stovepiped solution.” But, he said, if you keep doing that over and over, crisis after crisis, bespoke system after bespoke system — which is exactly what the DoD’s dozens of sub-agencies have done for decades — “they don’t talk to each other.”

The result is an ever-shifting patchwork of incompatible systems that can’t share data, even within a single military branch, let alone across the entire joint force. That present reality is incompatible with the Pentagon’s future goal of a JADC2 meta-network to share battle data amongst all the armed services across land, sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace.

“We’re going to have some requirements” for JADC2 developments, Martell said, “[but] we don’t think the right answer is making everything joint. We don’t think the right answer is taking away the ability for the services to specialize… [So] what’s the least amount of constraints we have to put on what the services build, so that data can flow up to the joint [level]?”

Cleaning up the data to enable better AI across the DoD is one of Martell’s top priorities. It’s also a major reason his office was created in the first place back in 2021 (news first broken by Breaking Defense), merging previously separate entities like the Chief Data Officer, the data-analytics initiative called ADVANA, the Joint AI Center, and the “bureaucratic hackers” of the Defense Digital Service.

To do that, “we really need your help,” he told an audience heavy on current and would-be federal contractors. “If you can be helpful with data labeling, if you can be helpful [with] data monitoring…we need to work with you.”

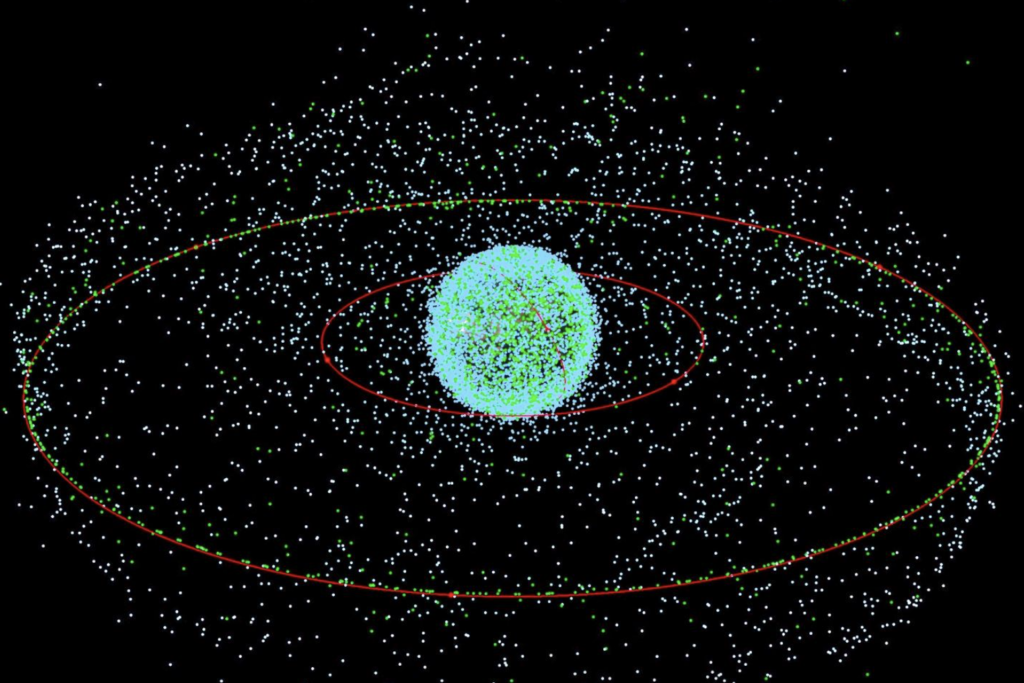

A data visualization of over 24,631 tracked objects in orbit. Active satellites imaged in green, inactive satellites imaged in gray. Red orbital rings at 1,000, 10,000, and 36,000 km altitudes. (CSIS Missile Defense Project with data from AGI and U.S. Space Force.)

Show Me The Data

Labeling and monitoring are just two parts of a rigorous process to build and maintain quality AI and analytics — with opportunities for the private sector at almost every step. In simplified form:

First, each database needs to have a “database product manager” assigned to it — a Department of Defense official whose job it is to keep it up to date, accurate, and above all usable by entities across DoD. “Their job rating is dependent upon it serving value for the customer,” Martell said.

Then, to make the data usable, especially to train machine-learning algorithms, it has to be labeled. That’s a laborious chore that requires at least one human who knows the specific subject matter — spare parts stockpiles, say, or precision missile targeting — to go through thousands of individual entries and categorize them.

“As warfighters…you are the experts,” Martell told the uniformed personnel in the room. “The military IP [Intellectual Property] is the labeled data.”

Once labeled, the data has to be made accessible, not just to its owners, but to the rest of DoD. But that doesn’t require ripping it out of its old home and dumping it in a newly created “data lake,” Martell emphasized.

“The data stays where the data is,” he said. “You can put it into a lake, I don’t care, [but] the best place for the data is with the owners of the data, the people who understand it the best.”

The best way to allow access to the data, Martell said, is through some kind of standardized Application Programming Interface. The data product manager must then publish the API used, metadata on the database’s contents, and a point of contact in a catalog for other agencies to reference. (This approach is what Martell calls a “data mesh”).

Once the API is in place, Martell went on, would-be users of the data can not only gain access but, with CDAO’s help, build software applications to exploit it. Sometimes that means feeding the data into an existing AI model or even using it to train new machine-learning algorithms, he said, but often it’s as (relatively) simple as displaying crucial data in a user-friendly dashboard, like ADVANA.

Those applications need to be tested and certified as reliable and secure, Martell went on. Then they need to be continually updated and regularly reevaluated to make sure they remain accurate in an ever-changing world.

“When we build these models, we train them from the past, [because] we don’t have data about the future,” he said. “If the world changes, your model won’t work or won’t work as well.”

Martell’s goal is to get companies on contract to help with almost every step.

“Data labeling as a service … we already have that in a pilot,” he said. “We’re just getting started on data transformation as a service. [And] please be on the lookout about model monitoring as a service.

“There’s already been RFIs [Requests For Information] for data mesh; respond to those,” he told the audience. “There will be RFIs for data monitoring; respond to them.”

Martell pledged that his office would be more forthcoming with information for industry from now on.

“The point of this symposium, both for government and for industry, is to let you know where we’re at,” he told the conference. “We were too quiet. We should have let you know a little bit more loudly. We’re gonna fix that going forward. And we’re gonna start with this symposium.”