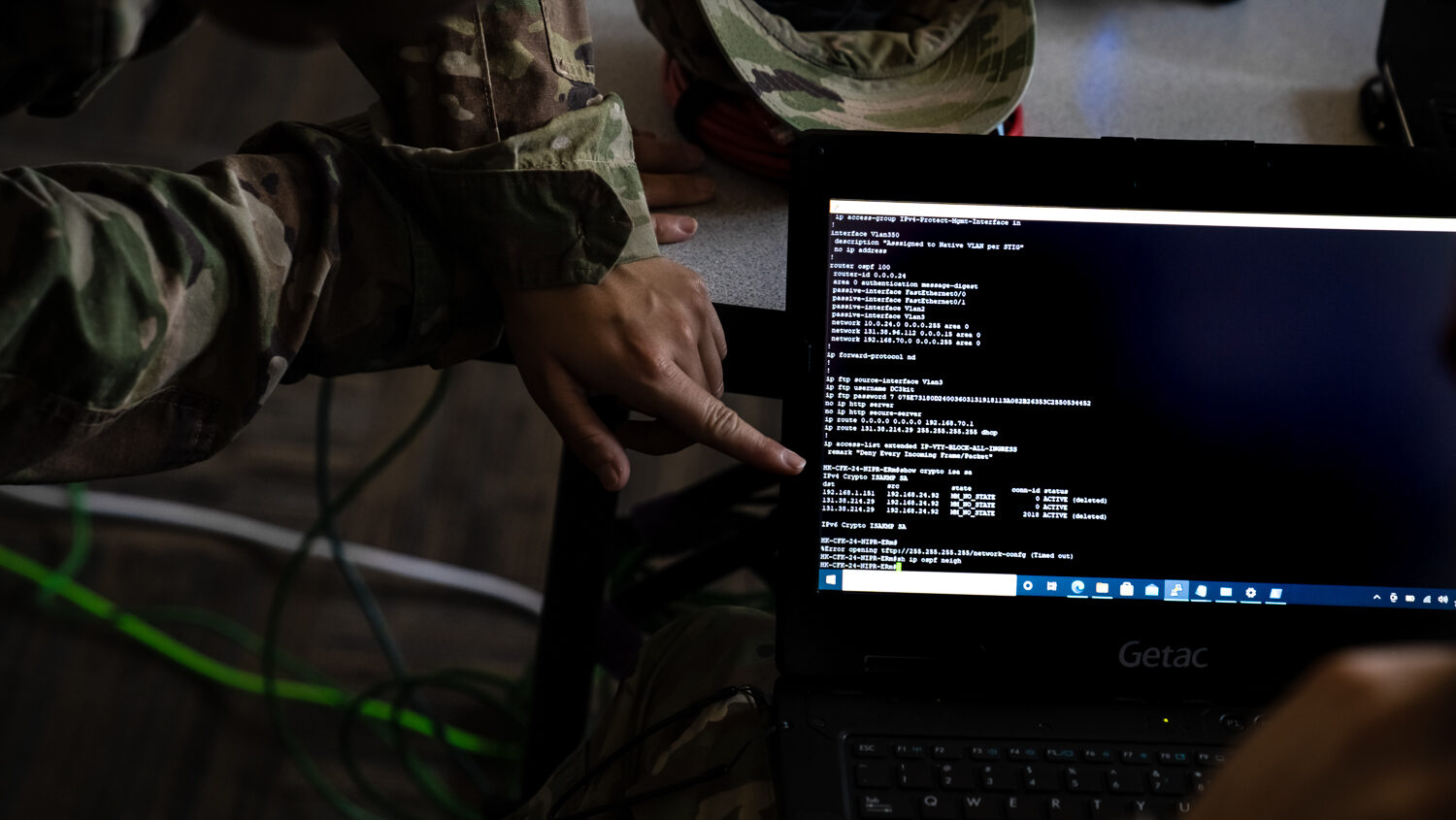

Members of the 56th Air and Space Communications Squadron at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam operate cyber systems using a Enhanced communications flyaway kit during the Global Information Dominance Experiment 3 and Architect Demonstration Evaluation 5 at Alpena Combat Readiness Training Center, Alpena, Michigan, July, 12, 2021. (U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Amy Picard)

WASHINGTON — In 21st century wars “commanders need to integrate vast amounts of data, from all domains and all sources,” the Pentagon’s new Chief Digital & AI Officer told a crowded ballroom at a suburban Hyatt this morning.

And to stay ahead of adversaries like China, CDAO Radha Plumb told an estimated 750 people in attendance, 500 of them contractors, “the United States’ decisive and enduring advantage lies in the innovation ethic inherent in the American economy. … That’s where you all come in.”

In 2023, a select team — drawn from across the Department of Defense and overseen by DoD’s first-ever CDAO, Craig Martell — powered through four “Global Information Dominance Experiments” to develop an operational version of the Pentagon’s all-service, AI-enhanced command-and-control system, known as CJADC2. In February, Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks publicly announced that this “Minimum Viable Capability” was “real and ready” for operational use.

But, as the name implies, the current capability is, well, minimal. It’s built around initial, barebones versions of just two killer apps. One is an automated advisor to suggest which weapons should hit which targets, known as the Joint Fires Network. The other is a “global integration” system to swiftly share intelligence and planning data across the military’s four-star Combatant Commands. The military wants both to beef up these two central capabilities and expand CJADC2 into a wide array of other functions.

RELATED: CJADC2: Let 100 applications bloom, not ‘one to rule them all,’ says GIDE director

To make CJADC2 more things to more people, however, the Pentagon needs to bring in a lot more companies. The year-long sprint to the “minimum viable” version moved fast, in part, by restricting itself to handpicked tech from only about two dozen companies.

By contrast, today’s industry day, the first for the GIDE experiments, drew reps from over a hundred vendors.

The details of what DoD from all those firms are classified, and reporters were politely asked to leave after the opening keynotes, but they got to sit down with Plumb for their own in-depth session.

For 2024 and beyond, “we want to bring in more technologists and technology solutions to compete [and] consider other workflows,” Plumb said. “We want to institutionalize a process for companies to come in … a predictable, repeatable process,” including industry days every quarter, one for each GIDE experiment.

How to Sell to CDAO: Tradewinds, Open DAGIR, & GIDE

The essential portal for firms wanting into GIDE is CDAO’s Tradewinds website, Plumb said. In this “streamlined process,” she explained, companies submit short pitches — often videos — on their products. CDAO evaluates them against identified military needs. Promising products get a chance to be field-tested by actual military operators in a GIDE experiment. Those that do well with the warfighters can win some kind of procurement contract.

The crucial nuance is that a product that gets picked via Tradewinds counts as “competitively selected” in terms of government acquisition regulations, Plumb explained to a recent CSIS webcast. That makes the product eligible for a procurement contract without further rounds of competition.

“You’ve got to prove out your technology, right?” Plumb emphasized to CSIS. “But then [Tradewinds] is a streamlined way to get onto those procurement-type vehicles,” typically using a congressionally created express lane called Other Transaction Authority.

Not every product pitched on Tradewinds will get picked for procurement, Plumb emphasized. “There are some things that should die in the ‘valley of death’ [and] not all things should be sustained … longer-term,” she said at CSIS. “There’re sometimes digital solutions that bridge [short term]. We want to make sure they’re funded for, let’s say, three to five years, but not, you know, enduringly into the future forever, because we actually want them to be deprecated in favor of future technology.”

That’s a revolutionary idea in the Pentagon, which tends to purchase tech through vertically integrated megaprograms, where a single prime contractor has the military customer in a “vendor lock” and innovative subcontractors at its mercy. But instead of locking in a prime like Palantir (for Maven Smart System AI-enabled intel) or Booz Allen (for Advana big data analytics), Plumb wants constant competitive “bake-offs,” including from smaller vendors.”

That’s why Plumb’s new framework for contracting at CDAO, known by the contrived acronym Open DAGIR, is all about decoupling different products and creating a flexible “open architecture.” That way the Pentagon can turn contracts on and also off as quickly as required, which Plumb argues is essential to stay on the cutting edge of AI for projects like CJADC2.

So, can GIDE vet tech fast enough that companies attending today’s forum can turn around, pitch a product, and get it field-tested by real military operators in the next Global Information Dominance Experiment, GIDE 12, this fall?

“We hope so,” Plumb told reporters. Both CDAO and industry need to rise to that challenge. “Have we clearly laid out the capability needs so industry can build us tech solutions?” she asked. “And then are those tech solutions ready for us to drop into the experimentation environment with our operators?”

“We’re trying to be easier to work with,” Plumb said. And as vendor reps emerged from the classified sessions for their lunch break, they seemed energized and optimistic. But the real test of the new approach will be when new tech gets into operators’ hands as the GIDE experiments build out the “minimum viable capability” approved last fall.

The human dimension is decisive, Plumb told reporters. “The reason we called it ‘minimum viable capability’ and not a ‘product’ is it’s not just the technology,” she said: It’s also about the processes, training, and intangibles.

“Was the warfighter actually able to use it? Did they want to use it or they like their old thing better?” she said. “If we meet those criteria and it is sufficiently value-aded, then we can look at whether we want a longer term contract.”