Electric Boat’s submarine-building yard in Groton, Connecticut

CAPITOL HILL: The top Democrat on the House seapower subcommittee sees a bright future for submarines, a bleak one for the Navy’s cruiser modernization plan, and a big question mark over the controversial Littoral Combat Ship. I spoke to Rep. Joe Courtney yesterday as the House Armed Services Committee rushed to finish its first draft of the annual defense policy bill, the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act, which will be rolled out Monday. Courtney and Republican seapower chairman Randy Forbes are, as usual, in bipartisan lockstep on their subcommittee’s portion of the bill, which is already published — though there’s one exception we’ll discuss below.

Rep. Joe Courtney meets with submarine officers.

Submarines: Full Speed Ahead

“So far, we’ve done extremely well,” said Rep. Courtney, whose Connecticut district is home to growing sub-builder Electric Boat. In the administration’s budget request, he told me yesterday, “there was a little bit of a shortfall in AP (advanced procurement) funding for one of the submarines for next year, 2017…. $85 million… That’s going to be restored” in the HASC bill.

The bill also gives new authorities to ease construction of the immensely expensive Ohio Replacement Program submarines, which will carry nuclear ballistic missiles. Those novel authorities might well be applied to other shipbuilding programs as well, Courtney said. “The appropriators might gag at the thought of that, but we’ve got to put our thinking caps on right now,” he said, because traditional funding mechanisms won’t sustain an adequate fleet under today’s tight budgets.

Overall, the Pentagon’s long-term plans continue pumping out two Virginia-class attack submarines a year — except in years when they have to fund a much larger Ohio Replacement sub, when Virginia production drops to one. The first such year is 2021, the second 2024. Courtney, Forbes, and assistant Navy secretary Sean Stackley are all working to keep construction at two Virginias a year, even in ’21 and ’24, and Courtney is increasingly confident it can happen.

“There’s been a real sea change — to use a pun — in terms of their perception of what the demand is” for submarines, Courtney said. And “listen to Stackley over the last couple of months or so: His confidence level is getting very high” in the industrial base’s ability to produce three subs simultaneously — a huge Ohio Replacement and two smaller Virginias — without costly bottlenecks.

The Virginia-class attack submarine USS North Dakota.

That said, the first crucial year, 2021, is far enough away that Courtney doesn’t have to meet the Jerry McGuire demand and “show me the money,” not just yet. “It’s too soon to do advance procurement funding for 2021,” he said. So far, “we’re basically following Stackley’s lead. (The bill) directs the Navy to come back to us with a plan for keeping two Virginia-class subs a year production in 2021 and those subsequent years in the ’20s.”

There’s a strategic imperative for sub production. The Navy’s current force of 54 attack submarines is already under pressure from Russia and China. European Command chief Gen. Philip Breedlove told Courtney’s subcommittee that we can no longer shadow Russian submarines one-on-one and must resort to “zone defense“; Pacific Command chief Adm. Harry Harris said outright he “suffers from a shortage of submarines.”

“With no prompting from me or Jim Langevin or Forbes, these guys were pretty adamant that all of the expectations about the undersea realm have changed in the last couple of years, in a way that I don’t think the intelligence community or anyone else foresaw,” Courtney said.

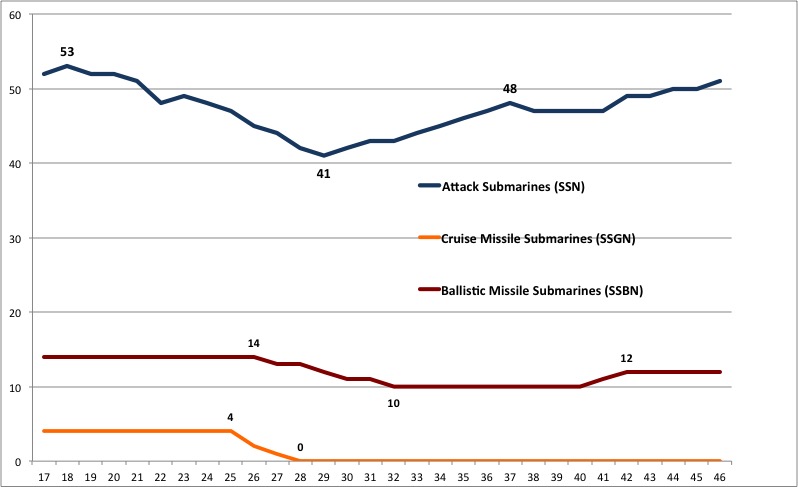

Submarines in service by type and year. Source: Navy 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan for 2017

The fleet’s official requirement is for only 48 attack subs, six short of the current fleet, but Courtney predicts that figure will go up once the Navy completes its ongoing force structure assessment. “Based on what’s going on out there and what we hear from Harris and Breedlove, it’s hard to imagine they could somehow stay put at where we are right now (i.e. 48), because those numbers were developed in a totally different environment,” when Russia and China were much less threatening, Courtney said.

“Having the fleet decline to 41 (attack submarines) is really unimaginable,” Courtney added. But that’s exactly what happens in the Navy’s current long-term plan. There’s also not a lot Congress can do about it, because aging Los Angeles-class submarines bought in bulk during the Reagan buildup are now retiring en masse as well, and no feasible production rate of Virginias can catch up.

“You’re right, this decline is because of decisions that were made really a couple of decades ago, and there’s not much you can do — except getting in a time machine — to change that,” Courtney admitted. “(But) if we add a sub in 2021, it actually mitigates that decline , so it doesn’t go all the way to 41.” Every sub matters, and every Virginia added to the budget makes the decline shallower and the recovery steeper.

The Ticonderoga-class cruiser Shiloh in dry dock.

Cruisers & LCS: Slow And Unsteady

Courtney was less sanguine about surface warships, specifically the aging Ticonderoga-class cruisers and the new Littoral Combat Ships, both of which have caused years of wrangling in Congress.

“I’ve been to a lot of these painful LCS hearings,” Courtney told me. “This saga seems like it’s never-ending, (but) there are missions they provide a great deal of value to, especially minesweeping.”

The latest twist in the LCS “saga” is Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s decision to cut the program from 52 ships to 40, and from two variants built at two shipyards to one variant built at one yard. “We got a very mixed message from the administration,” Courtney said. “The Navy still testified that their requirement is still 52… and the decision to downselect to one shipyard so quickly had people’s heads spinning.”

“A new administration… deserves in my opinion to get a fresh look at it before something as drastic as closing a shipyard occurs,” Courtney said. So the draft HASC bill adds a third LCS to the budget to keep both yards in business longer.

The two Littoral Combat Ship variants, LCS-1 Freedom (far) and LCS-2 Independence (near).

As for the cruisers, they caused one of the rare breaches between Courtney and the Republican chairman, Randy Forbes. After much painful back and forth, Congress had reached a compromise between the Navy’s original plan to retire 11 aging cruisers and hawks’ desire to modernize all 11: Take two cruisers offline each year for modernization, with the modernization period not to exceed four years, and no more than six cruisers to be thus sidelined at any given time — the 2/4/6 plan. Last year Forbes proposed accelerating to a two-year modernization period — 2/2/6 — and Courtney reluctantly opposed him.

“It was the only time we’ve really parted ways since I’ve been ranking (member),” Courtney told me, but 2/4/6 was too hard-fought a compromise to unravel. “I lost that vote in committee,” he said, “but at the end of the conference (with the Senate), 2-4-6 was still the law of the land.”

This year, the threat to the 2/4/6 compromise comes from the Navy, which proposed taking seven cruisers out of service at once. Once again, Courtney says no way.

The Navy’s argument for seven-at-a-blow “really was not convincing enough,” Courtney told me. “They’ve got to come up with a better way to reassure Congress” that it’s not a backdoor approach to retiring the cruisers altogether, he said. The cruiser issue has become so fraught it’s not about nuances of policy anymore, Courtney told me: “They’ve go to come back with something… that increases the trust factor.”

Marines new ‘Fusion Center’ aimed transitioning cutting edge tech more smoothly

Marine Corps officials said the new office will act as a bridge over the Pentagon’s infamous “valley of death” and will first focus on counter-drone systems.