LAS VEGAS: Drones rule the skies over Afghanistan. But the next war may be a different story. “We’re fighting cavemen that aren’t shooting back,” said Lt. Col. Kevin Murray. “That’s not where we’re going.”

LAS VEGAS: Drones rule the skies over Afghanistan. But the next war may be a different story. “We’re fighting cavemen that aren’t shooting back,” said Lt. Col. Kevin Murray. “That’s not where we’re going.”

An enemy more high-tech than the Taliban — which doesn’t take much — could jam or hack the datalinks used to control American drones, or just plain shoot them down. Last year, Iran reportedly brought down a RQ-170 spy drone with a cyber attack. To survive in unfriendly skies, Murray said, unmanned aircraft must be “joint, common, interoperable, and survivable — and we are none of those things right now.”

Murray’s a Marine Corps fighter pilot who now commands Marine UAV Squadron 1 (VMU-1). But at this week’s conference of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) in Las Vegas, where Murray spoke on Thursday, it was clear that his concerns about drones are shared, albeit in more diplomatic language, at the highest levels across the services.

“Through most of the last decade,” said Vice Admiral William Burke, the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Systems, “they [drones] have been able to operate in a permissive environment, neither congested nor contested. [In the future], frequently the environment will be physically and electronically contested.”

“It is a huge challenge,” Burke told the audience Thursday at AUVSI. “Fortunately, this sounds more like an engineering challenge than an impossible task” — but, he added, “I don’t know how close we are.”

Maj. Gen. James Poss, the Air Force staff’s head of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, raised the same point in a panel discussion the previous day — but in much less urgent terms. “We do recognize the need to operate in denied areas,” he said. “We think that we’re going to have a need to have this capability certainly available by the early to maybe mid-twenties, [and] we are watching with great interest what our brothers and sisters in the Navy are doing with their program.”

The two services are coordinating more than ever before under the controversial concept for penetrating high-tech defense networks known as “AirSea Battle,” Vice Adm. Burke agreed: “The work we’ve done on AirSea Battle has brought us much closer together.”

In terms of programs, though, the two services are taking very different paths. With manned aircraft, the Air Force took the lead on stealth, starting with the F-117 stealth fighter in the eighties, followed by the B-2 bomber and F-22, while the Navy trusted in its non-stealthy Super Hornet augmented by anti-radar jamming. With stealth for combat drones, it’s the other way around.

The Navy is on the cutting edge with its X-47B UCAS (Unmanned Combat Air System), now in tests at Patuxent River, Maryland. Admittedly, the UCAS is only a “demonstrator” — a kind of proto-prototype — to work out the technology of operating unmanned jets off aircraft carriers. But the Navy plans to start work soon on an actual operational stealth drone called UCLASS (Unmanned Carrier-Launched Surveillance and Strike), which is set to enter service, perhaps optimistically, in 2019-2020.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has no stealth strike-drone program — at least outside the “black” world of classified programs, which is where the F-117 program hid for years, so it is possible the Air Force has a stealth ace up its sleeve. In this week’s public forum, Maj. Gen. Poss just spoke vaguely of the service’s interest in a “next-gen RPA” (remotely piloted aircraft), sometimes called MQ-X. The service has also pondered making its next-generation long-range bomber “optionally manned,” that is able to fly either with or without a pilot. In the nearer term, Poss suggested, if you took the electronic countermeasures now standard on F-16 fighters and put them on a drone, “even our current generation of RPAs, they’re surprisingly survivable in denied territory.”

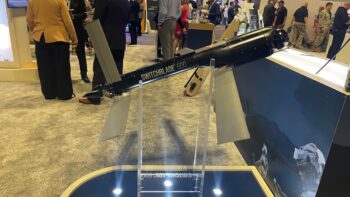

“Even the Navy itself is struggling on the best way to execute” missions in high-threat airspace, Maj. Gen. Poss said. “Is it best to go low-observable [i.e. stealthy]?” he asked. Or, he went on, instead of investing heavily in stealthy platforms you expect to get back, “do you swarm” with large numbers of cheap, expendable, “attritable assets”? Is the right solution to secure communications against sophisticated jamming and hacking, so the remote operators can retain control even deep in hostile airspace? Or is it wiser to expect the enemy to disrupt the datalinks somewhat and make the drones smart enough to operate on their own? “Can you really teach these aircraft to be fully autonomous?” Poss asked. “This is an area where we’re generally open to suggestion from our industry partners.”

Vice Adm. Burke was less meditative and more forceful, strongly skeptical about autonomy and emphatic about the need for secure datalinks. Better “machine-learning algorithms” are important, he told the audience of drone makers and researchers, but “artificial intelligence has been about ten years away for the last 25 years, so get on that, will ya?” His favored solution was clear: “We must develop a robust communications suite to operate in the A2/AD [anti-access/aerial denial] environment,” he said flatly. “It must be jam-resistant,” yet have ample bandwidth for the drone to transmit back the data it collects.

Right now, though, said Lt. Col. Murray, the Marine drone commander, most drones don’t even have Link-16, the NATO standard for datalinks first established in the 1990s. In the benign airspace over Afghanistan, Marine operators can control their Shadow drones just fine, he said, but they must rely on voice communications over radio to talk to troops on the ground. (Text chat is sometimes an option, but only with static command posts, not troops on the move). “The biggest number-one issue is we can’t talk to the people we need to… digitally,” Murray said. “[There are] no encrypted datalinks.”

When Marines did implement Link-16 on some of their drones in theater, Murray said, the improvement was “amazing.” Just being able to get onto the Link-16 network used by manned aircraft allowed them to see much more clearly what else was in the airspace and prevent at least ten “mishaps.”

So, said Murray, “we put a JUONS [Joint Urgent Operational Needs Statement] forward in theater to try to equip every Predator, every Reaper, every Shadow, every Eagle, every everything with Link-16.” Getting that done in today’s tight budget environment may be tough — and it will still be only the first step towards drones that can take on enemies tougher than the Taliban.

UK picks 90 suppliers to support Hypersonic strike program

The various suppliers were all picked to join a Hypersonic Technologies and Capability Development Framework (HTCDF) agreement, making them eligible to compete for eight lots worth a maximum value of £1 billion ($1.3 billion) over the next seven years.