WASHINGTON: This Saturday the Navy will christen its newest nuclear-powered submarine, the $2.6 billion USS Minnesota at the Newport News shipyard in Virginia. Countless movies have cemented the popular image of subs as stealthy underwater killers, stalking hapless surface vessels with periscope and torpedo. But today’s Navy is experimenting with launching robotic mini-subs and even unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) from Virginia-class attack subs like the Minnesota.

WASHINGTON: This Saturday the Navy will christen its newest nuclear-powered submarine, the $2.6 billion USS Minnesota at the Newport News shipyard in Virginia. Countless movies have cemented the popular image of subs as stealthy underwater killers, stalking hapless surface vessels with periscope and torpedo. But today’s Navy is experimenting with launching robotic mini-subs and even unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) from Virginia-class attack subs like the Minnesota.

In Navy tests of a mini-UAV called Switchblade, “you can launch it, you can control it, you can get video feed back to the submarine,” said Rear Adm. Barry Bruner, chief of the undersea warfare section (N97) on the Navy staff, at the recent Naval Submarine League symposium in suburban Washington. Future subs could also launch unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) to scout ahead stealthily beneath the surface. “It sure beats the heck out of looking out of a periscope at a range of maybe 10,000 to 15,000 yards on a good day,” Bruner said. “Now you’re talking 20 to 40 miles.”

Pair that sensor range with new long-range torpedoes — yet to be developed — or submarine-launched missiles, and you dramatically increase the kill range of the current submarine fleet, Bruner enthused. “It’s phenomenal, it’s asymmetric, and it’s cheap, [and] we’re not that far away.”

Some informed observers are more skeptical. The sub-launched UAVs and UUVs are still experimental. A “universal launch and recovery system” to get the small robots off the sub and then, critically, back on again is still in development — and current attack submarines like the Minnesota lack the large-diameter launch tubes to accommodate the system anyway, although the next-generation “Block III” Virginia-class subs entering service in 2014 will be able to. The Navy is also designing a “Virginia Payload Module” that would increase future submarines’ launch capacity, but it’s uncertain whether actual development will get funded.

“They seem to be in a period of experimentation that doesn’t have any obvious or clear end point,” one congressional staffer told Breaking Defense. “I can’t tell you exactly where they’re headed.”

What’s more, while sub-launched drones are a new idea to American admirals, “the Israelis experimented with it more than than 20 years ago,” said naval historian Norman Polmar. “The US Navy’s just been horribly slow.”

In some respects, said Polmar, the Navy’s even gone backwards. Submarines have long been able to launch missiles from underwater. (And a missile is just a crude drone that doesn’t come back). But the Navy phased out the sub-launched version of its Harpoon anti-ship missile years ago, and the Tomahawk cruise missiles that submarines currently carry can only attack targets on the land. So today’s sub fleet can strike ground targets deep in enemy territory, but it’s arguably less capable against enemy surface ships that it was 20 years ago.

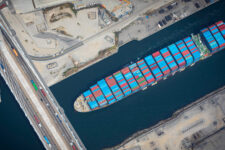

At stake is not just the combat power of individual submarines, but the Navy’s future vision for the entire fleet. The objective: to integrate the traditionally lone-wolf underwater hunters into a digital battle network that links submarines to surface ships to aircraft to satellites. The opponent: the multi-layered, high-tech, “anti-access/area denial” defenses — long-range anti-air and anti-ship missiles, cyber-attacks, sea mines — being developed by emerging powers, most of all by China.

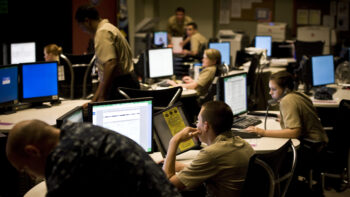

This emerging interservice doctrine, known as “AirSea Battle,” is “very much a team sport,” said Vice Adm. Michael Connor, the Navy’s Commander of Submarine Forces (COMSUBFOR), at the Naval Submarine League conference. “We know what part we play in that team,” he went on. “We’re sort of the wide receivers, more or less, getting down field.”

The Navy has struggled to build stealthy surface ships, like the immensely expensive DDG-1000 class, and it has yet to field its first stealth fighters. But submarines have been a stealth weapon for over a hundred years. Even today, in the face of advanced sonars and spy satellites that can peer hundreds of feet below the surface of the water, submarines are harder to detect than any stealth aircraft.

In peacetime, that invisibility puts them in high demand for covert reconnaissance. In wartime, it would make them the leading edge of US naval power, slipping unseen into waters where other forces dare not go, then launching long-range weapons like Tomahawk cruise missiles to crack open enemy defenses and to let less-stealthy forces in.

The new role of operating as part of a networked fleet requires not just new equipment but a new mindset. “Submariners like to sink ships; they don’t like to do other things,” said Polmar. “They’re being forced to change and broaden that… The submarine community now realizes they have to be part of the bigger picture.”

Tensions between Navy and industry in the spotlight: 2024 in review

Industry and the Pentagon always have their disagreements. But those usually stay behind closed doors.