WASHINGTON: After years of grudging refusal to do much more than discuss the possibility of talks on a space code of conduct, China has begun discussions on a multilateral code as part of a larger UN effort, as well as committed to specific goals known in the trade as “transparency and confidence-building measures” (TCBMs).

WASHINGTON: After years of grudging refusal to do much more than discuss the possibility of talks on a space code of conduct, China has begun discussions on a multilateral code as part of a larger UN effort, as well as committed to specific goals known in the trade as “transparency and confidence-building measures” (TCBMs).

“It is an extremely positive step that representatives of the international community were able to agree on activities that can lead to a more predictable, stable environment. This is part of a trend where space stability issues are often more effectively discussed using norms of behavior (versus a treaty-based approach),” says Victoria Samson, DC director of the Secure World Foundation, who’s one of the few people outside the US government who know much about this intensely technical subject.

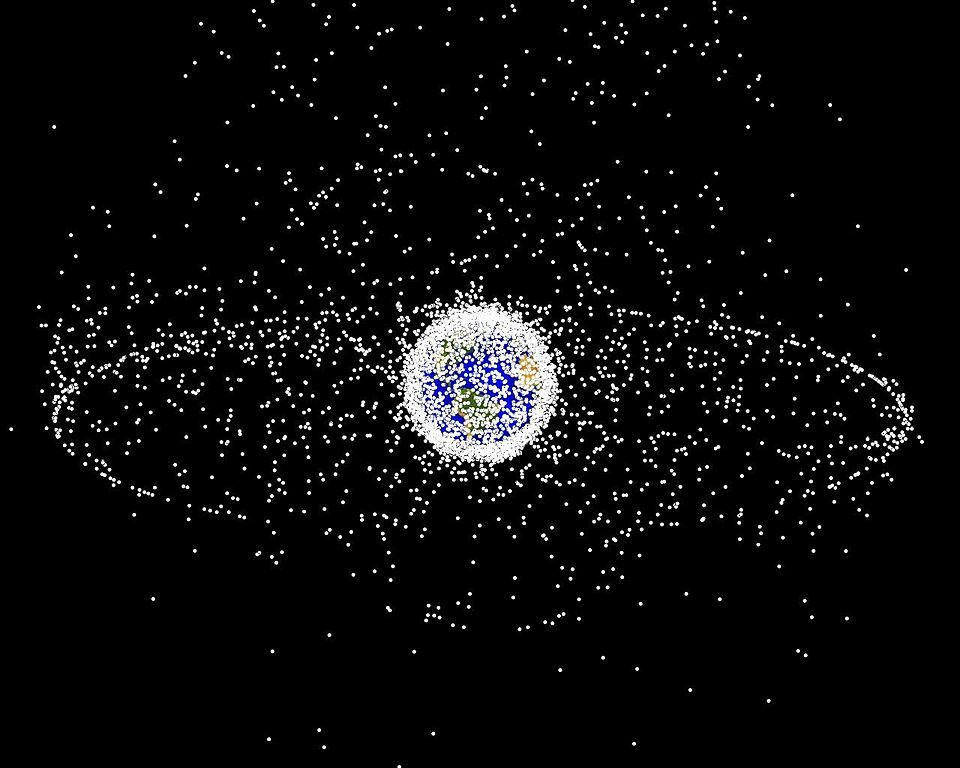

The long term stakes for these efforts are enormous: preserving the ability of every country to send satellites and people into space safely, operate safely and make use of the incredibly precious orbits that allow much of today’s and tomorrow’s economies to function globally and efficiently. Not to mention that it also preserves military access to the ultimate high ground. That may be why the Chinese position appears to be shifting.

The Chinese “have displayed more transparency than they have in the past,” a senior State Department official said, noting the change in approach. But, the US and other countries “are at the very early stages of this discussion with China.” The shift in Chinese policy began “about a year ago.”

The consensus achieved is reflective of a shift in China’s poistion on space conduct, which had generally been opposed to international agreements the Chinese felt might be restrictive and help lock in European, American, and Russian advantages in space. That did not change — and may have gotten tougher — after the Chinese created enormous amounts of space debris when they destroyed one of their defunct satellites in an anti-satellite weapon test in January 2007.

The consensus was achieved as the result of work by the wonderfully-named UN Group of Governmental Experts on Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Outer Space Activities.

The group’s report detailing the TCBMs (as they are known in the space policy community) will be released in a few weeks, the senior State Department official said. The State Department release offered this general description: “enhance the transparency of outer space activities, further international cooperation, consultations, and outreach, and promote international coordination to enhance safety and predictability in the uses of outer space.”

The agreement was announced Friday by the State Department in a little noticed release wrapped deep in diplomatic lingo. It is all part of what the senior State Department official described as a three-pronged effort to improve international space cooperation and improve both the ability of governments and of companies to operate in space over decades.

Let’s delve into this a bit, because these negotiations reveal a great deal about the complexity and breadth of the talks on space debris, space situational awareness, and a myriad of other space policy issues. The GGE is composed of 15 experts from the governments of Brazil, Chile, China, France, Italy, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Those experts acted as individual experts — not accredited diplomats — on behalf of their governments.

They held their first meetings in July last year and the second batch in April. The final meetings, where “consensus” was achieved, were held in New York from July 8-12. This is the first such agreement reached since 1993.

Here’s what drove the agreement, as stated in the State release: “The globe-spanning and interconnected nature of space capabilities and the world’s growing dependence on them mean that irresponsible acts in space can have damaging consequences for all. As a result, all nations must work together to adopt approaches for responsible activity in space to preserve this right for the benefit of future generations.”

The other two prongs of the US approach on maintaining and improving the long-term uses of space are the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and the European Union’s pursuit of an international code of conduct in space. The EU code was “noted” in the consensus agreement, but it was not adopted as a model or as a goal. It’s likely this is because the China found it too restrictive. COPUOS is focused, the State Department official said, “on long term sustainability” of space operations, while the GGE were focused on the more limited transparency and confidence building measures.

This consensus doesn’t mean all is bright and happy in terms of space policy, as Samson makes clear. Russia and China both continue to press for another wonderfully named effort: the Treaty on Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects (known to the international space policy community as the PPWT).

“China and Russia are still holding out hope for the PPWT – their proposed treaty for the prevention of placement of weapons in space, and they have said that a soft law approach can be complementary to it,” Samson says. “However, there is no way that the United States will agree to the PPWT. None. But I’m thinking that China and Russia’s clinging to it is more a matter of national pride than concern about space-based missile defense (which the PPWT would prevent).”

The fact that this latest consensus has been reached is encouraging, Samson believes: “And in my mind, it’s the process – the negotiations – that matter. Rules of the road take a while to emerge. Having open, honest discussions about priorities and concerns in the interim can help shape those rules.”

China creates new Information Support Force, scraps Strategic Support Force in ‘major’ shakeup

A PLA spokesman said the Information Support Force “is a brand-new strategic arm of the PLA and a key underpinning of coordinated development and application of the network information system,” which would seem to indicate a sharp focus on networks.