WASHINGTON: The senior leadership of the US military knows that genetically modified humans — stronger, faster, or better at altitude — and intelligent machines that could kill without remorse and with enormous efficiency, are two of the thorniest policy nettles they must grasp.

Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work firmly grasped that nettle today, saying the United States would not grant artificially intelligent weapons or other automated systems the right to kill. He hedged a bit on whether the US military would genetically modify humans, saying “that is really, really troubling.”

Asked by the Washington Post’s well-known columnist, David Ignatius, how the US would counter an enemy willing to give robots lethal authority, Work danced around a bit describing the difference between “assisted” and “enhanced human operations”: the first is computers and sensors improving human performance, the second is genetically modifying humans. “Right now, we think in terms of assisted human operations,” Work said.

If you comb through DARPA’s work, such as that coming from the Biological Technologies Office, the ragged edges of work that could lead to improved human beings can be seen.

For example, its Biological Robustness in Complex Settings (BRICS) program is focused on this:

“The development of techniques and tools to rapidly sequence, synthesize, and manipulate genetic material has led to the rapidly maturing discipline of synthetic biology. Potential applications of synthetic biology range from the efficient, on-demand bio-production of novel drugs, fuels, and coatings to the ability to engineer microbes capable of optimizing human health by preventing or treating disease.

“If applications such as those highlighted above are to come to fruition, methods to increase the biological robustness and stability of engineered organisms must be achieved while maintaining or enhancing assurances of safety. While this program will support the development of technologies that would be prerequisite to the safe application of engineered biological systems in the full range of environments in which the Department of Defense (DoD) has interests, all work performed in this program will occur in controlled laboratory settings.”

Some of this genetics work has arisen because biological weapons remain perhaps the top potential threat to the United States (whether attacks are aimed at our crops, our people, or our water). Protecting humans against such attacks may require rapid development of counteragents or built-in genetic changes. As the above quote makes clear, the program will do its work “in controlled laboratory settings.”

Of course, work on prosthetics also can bring with it the ability to give humans much greater strength or speed or endurance without genetic modifications.

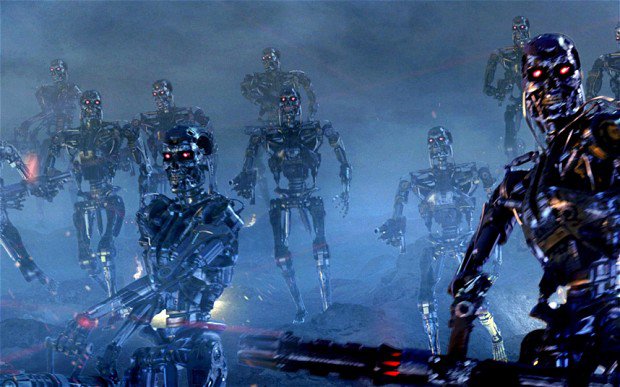

Work’s comments follow those of Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Paul Selva on what he called the Terminator Conundrum.

I asked Selva about this issue in January and here’s what he said:

“Where do we want to cross that line, and who crosses that first?” Selva said regarding the potential to embed microelectronics in human beings. “When do we want to cross that line as humans? And who wants to cross it first? Those are really hard ethical questions.” He called for an international debate on this, clearly thinking of amendments or additions to the existing Geneva Conventions or of a new set of internationally agreed to standards.

It sounds as if Bob Work might welcome such a debate.

Best line of Work’s discussion with Ignatius sprang from the JICSPOC, the unpronounceable acronym for an experimental space command post: “You have to have spock (sic) in something about space.”

Major trends and takeaways from the Defense Department’s Unfunded Priority Lists

Mark Cancian and Chris Park of CSIS break down what is in this year’s unfunded priority lists and what they say about the state of the US military.