Polar bears investigate the surfaced submarine USS Honolulu in 2004

PENTAGON: Polar bears. Wind chill of 20 below. Ice floes drifting faster than ever thanks to global warming. Cutting holes in the ice big enough to drop unmanned mini-subs through. Keeping mini-drones aloft in the frigid winds to watch out for the aforementioned bears. Those are just some of the issues — many of them new — that Navy sailors face as they set up camp for Ice Exercise 2016.

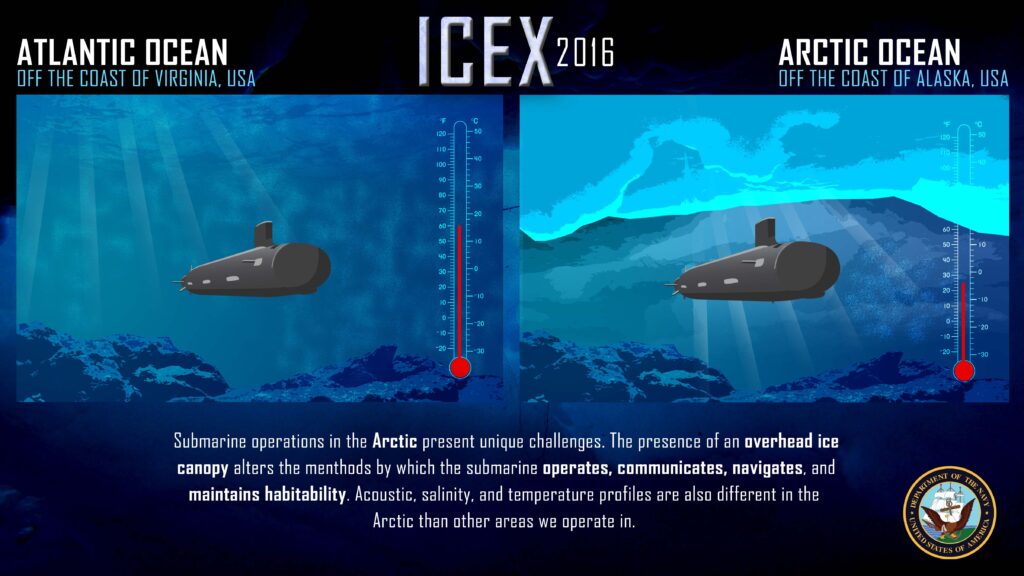

Navy operations in the Arctic declined after the Cold War, but in recent years they’re ramping up again. That said, officials insisted yesterday that ICEX is not a response to Russian militarization of the far north (or to Chinese probing, for that matter).. Instead, they told reporters, the focus is simply on better understanding a rapidly changing environment so Navy forces — principally submarines but increasingly unmanned vehicles — can better operate there for whatever purpose.

A submarine surfaces near the base camp for a previous ICEX

It’s easy for strategists and pundits to sit in toasty Washington and say the Arctic is opening up. In the long term, it’s even true. There will eventually be weeks and even months of the year where surface ships can transit the Arctic Circle unimpeded by ice. But actually surviving up there, let alone conducting military missions, is still harder than almost anywhere else on earth — hence the Navy’s push for more research.

“High of five, low of zero [degrees Fahrenheit] — it’s not Disneyland,” said Navy Capt. David Kirk, head of the Navy staff’s “Undersea Influence” branch (OPNAV N974). In fact, it’s a lot like the Ninth Circle of Dante’s Inferno (that’s the cold one), complete with six months of night — unbroken blackness — every year. Under the ice, he told reporters, it’s a challenge just to keep a submarine’s systems from freezing.

The Navy’s new fleet of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) has their own problems up north, said Scott Harper, head of Arctic Research at the Office of Naval Research (ONR). Usually, unmanned mini-subs in trouble have the option to surface and “phone home” or check their position against GPS, he said. But those signals don’t penetrate the ice, and UUVs are too small to break themselves a hole in the ice the way manned subs can. Autonomous systems are a big part of the Defense Departments future, but to get them to function in such extreme conditions, Harper said, roboticists have to find new and more “elegant” solutions.”

Even the liquid water can pose a problem. The Arctic Ocean has uniquely strange layering: warmer water on the bottom, colder water on top — the opposite of everywhere else on Earth — with a thin layer of freshwater from melting ice floes on the surface. The resulting mix of temperatures and salinity messes with the buoyancy of UUVs and the propagation of sonar.

So a huge amount of ICEX research is just testing sensors: from the UUVs, from the two manned attack submarines that will be involved, and from static hydrophones lowered through holes in the ice.

The other part is meteorological. The warming climate actually makes the Arctic harder to figure out, Harper said. The edge of the ice pack has become more dynamic, melting back in summer, only to refreeze in fall. The result is short-lived, local patches of open water and a lot of thinner but much more mobile ice. The floe under the ICEX base camp is currently moving at nine miles a day, Harper said, much faster than in most exercises past.

However, one aspect of Arctic operations is getting easier: communications. Traditional satellites orbit lower latitudes and give poor coverage in the Arctic Circle. But now four of a planned five MUOS satellites have been launched, literally giving our forces a new angle on the Arctic. “We will be using that system [and] we’ve been very pleased with that,” said Cdr. Ronald Piret from the office of the Navy Oceanographer.

Besides satellites, subs, and robots, ICEX 2016 will also involve some human divers and small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), though the drones will just be doing perimeter checks (e.g. for polar bears) rather than scientific research. All told, about 200 people will participate in ICEX on the surface, although no more than 80 will inhabit the ice camp at any given time. That includes Brits, Canadians, Norwegians, US Army soldiers, Coast Guard sailors, the Alaska Air National Guard — which is airdropping supplies — and several civilian US agencies.

No Russians are involved, but the Navy officials took pains to emphasize the exercise isn’t directed against them. “We’ve been conducting ICEX for years…. not driven at all by perceived adversaries,” said Kirk. And there are other fora in which we cooperate with Russia, such as the Arctic Council, one of whose meetings just happens to be scheduled to coincide with the month-long ICEX. (Also coinciding with ICEX: The Norwegian-led Cold Response 2016 exercises, with 15,000 troops participating — including 1,900 US Marines — which do have a more distinctly martial flavor).

“Our goal is not to militarize the Arctic,” said Jeffrey Barker, a civilian policy official on the OPNAV staff. “The president’s clearly stated that, our national objectives clearly state that.”

China’s new H-20 stealth bomber ‘not really’ a concern for Pentagon, says intel official

“The thing with the H-20 is when you actually look at the system design, it’s probably nowhere near as good as US LO [low observable] platforms, particularly more advanced ones that we have coming down,” said a DoD intelligence official.