M1 Abrams tanks of the 1st Cavalry Division in a NATO Atlantic Resolve exercise in Latvia.

CAPITOL HILL: “We are outgunned — outmanned — outnumbered — outplanned,” George Washington raps in Act I of the hit musical Hamilton. Few American commanders since the Revolution have had to worry about being inferior to the enemy in both numbers and technology. But between rising threats, declining US manpower, and steep cuts to Army modernization, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster told the Senate, being outgunned and outmanned might become the norm — so we’d better stop shrinking the Army before it’s too late.

“We are outranged and outgunned by many potential adversaries,” McMaster said, “[and] our army in the future risks being too small to secure the nation.”

The largest service is officially on a path down to 980,000 soldiers — 450,000 full-time regulars, 530,000 mostly part-time troops in the Reserve and Guard — but with manpower the military’s biggest expense, further reductions are definitely up for debate. Army leaders have said repeatedly that 980,000 is “minimally sufficient” for a major war, and even then only at “high risk” of casualties. As the Army’s official futurist — the deputy commanding general of Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC) for “futures” — the famously outspoken McMaster went further today.

“As we look to the future sir, we think that risk will become unacceptable,” McMaster told the Air-Land subcommittee of Senate Armed Services yesterday afternoon. Even now, he said, “we’re having a harder and harder time for the smaller force to keep pace with increasing demand.”

H.R. McMaster

The danger comes from two factors: “the [declining] size of the total force… in combination with the [lack of] modernization,” McMaster said. For example, “we have no current major ground combat vehicle development program underway,” he said. “The Bradley fighting vehicle and the Abrams tank will soon be obsolete” — as anti-tank weapons outstrip their armor — “but they will remain in the Army inventory for the next 50 to 70 years.”

This is unfamiliar and uncomfortable territory for American soldiers. In World War I and II, the US had the advantage of numbers; in the Cold War, it had better technology — with a few ugly exceptions like Task Force Smith in Korea. Since 1950, in particular, no American soldier has died to enemy air attack. Since 1950, US ground forces could count on American command of the air. Indeed, since 9/11, even small patrols that got into trouble could generally rely on precision-guided airstrikes to blast them a way out of it.

“We made the assumption several years ago that we’d be able to achieve and maintain air supremacy,” McMaster said. The war in Ukraine puts that in doubt.

Russia, China, and their customers have layered systems of radars and anti-aircraft missiles — what’s known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) — that may be able to keep US aircraft out. The only fire support left to the Army might be its own artillery units, which have been cut back and minimally modernized on the assumption that airpower would be available. Conversely, Russia and China have invested heavily in long-range rockets and surface-to-surface missiles with more range and power than American artillery.

Russia, China, & co. are also increasingly capable of electronic and cyber attack to jam or hack the wireless networks on which US forces rely. Even if airpower or artillery is available, you might not be able to call it up and transmit the coordinates to strike.

Russian ability to shut down Ukrainian networks has “been a real wakeup call,” McMaster said. The Army already has a (somewhat anemic) plan to rebuild electronic warfare capabilities disbanded in the 1990s, but they’re aware they must go further. “We convened a team of expertise to figure out what can we do now,” McMaster said, which will be working over “the next few months.”

Regardless of the task force’s recommendations, it’s clear the assumptions behind the current sizing of the Army no longer hold. “We had been able to have smaller forces have bigger impact because we weren’t as challenged in the cyber/electromagnetic domains, in the aerospace domain,” McMaster said. Now, he said, it’s clear “we can’t rely on maintaining dominance in any domain.”

If we can’t count on technological dominance, therefore, we need the insurance of adequate numbers. But Army commanders — and sympathetic members of Congress — fear the current cuts are going too deep. McMaster compared them to the infamous cuts of the post-Cold War era. Back in 1993, “when the world was a much safer place,” McMaster noted — with Russia prostrate and China just starting to rise — Colin Powell’s “Bottom-Up Review” called for an army of 484,000. Today, he said, “we’re going to 34,000 less in the active force.

But Congress can’t just vote for more soldiers without also voting money to pay them, subcommittee chairman (and army veteran) Sen. Tom Cotton emphasized. Otherwise, McMaster and his fellow Army witnesses agreed, the service would have to gut other accounts — definitely modernization and possibly readiness as well — to pay the personnel bill. The result, McMaster said, would be “disastrous.”

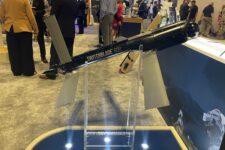

Taking aim: Army leaders ponder mix of precision munitions vs conventional

Three four-star US Army generals this week weighed in with their opinions about finding the right balance between conventional and high-tech munitions – but the answers aren’t easy.