US CENTCOM data

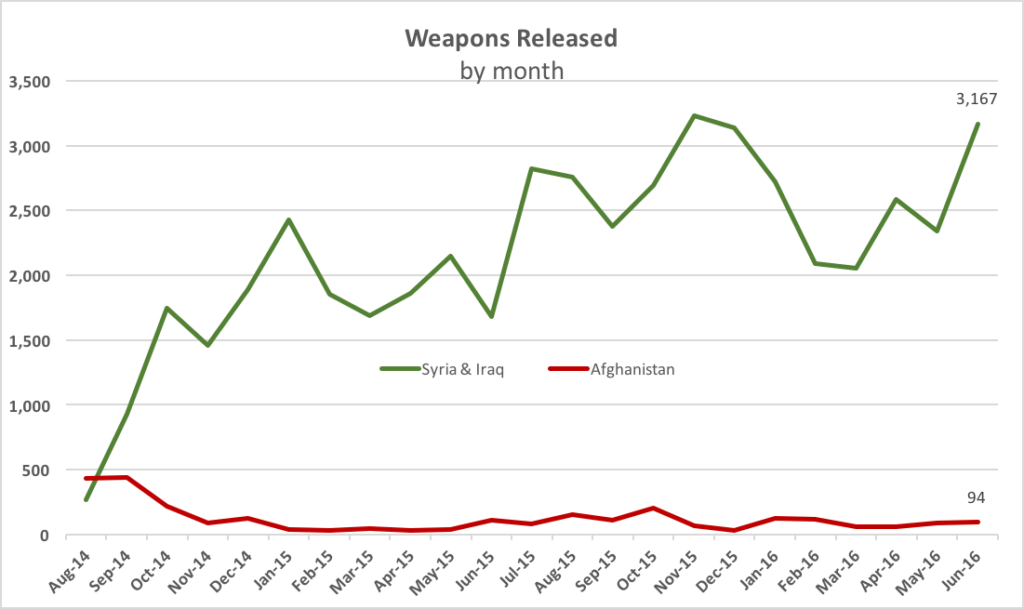

America is waging two very different wars at once. New data from the Defense Department shows the air campaign against the Islamic State escalating back to near-record intensity after a four-month (relative) lull. Meanwhile, airstrikes in Afghanistan are down to a tiny fraction of the bombardment in Iraq and Syria, but Afghanistan’s vast and rugged wastelands soak up a staggering amount of reconnaissance.

We analyzed the latest data from Central Command, which runs both wars. Released yesterday, the CENTCOM report gives month-by-month figures for how many bombs have been dropped and missiles launched, noting that “June was an extremely kinetic month, where near record numbers were achieved.”

Almost all of that violence — 97.1 percent — was directed at Daesh. (That’s the derogatory Arab acronym for the self-proclaimed Islamic State). In June, US forces released 3,167 weapons of all kinds in Iraq and Syria, compared to just 62 in Afghanistan.

US CENTCOM data

It’s worth noting that rules of engagement in Afghanistan got tighter after the errant bombing of a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz killed at least 42 people. Those restrictions have recently been loosened again to allow more strikes on the Taliban. But the fundamental dynamic doesn’t change: US forces are leading the fight in Iraq and Syria, blasting Daesh so Iraqi forces can advise, but in Afghanistan, they’re primarily advising and assisting.

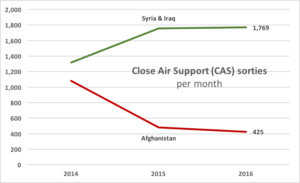

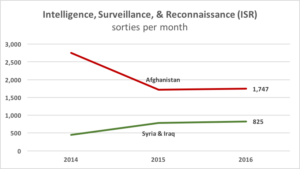

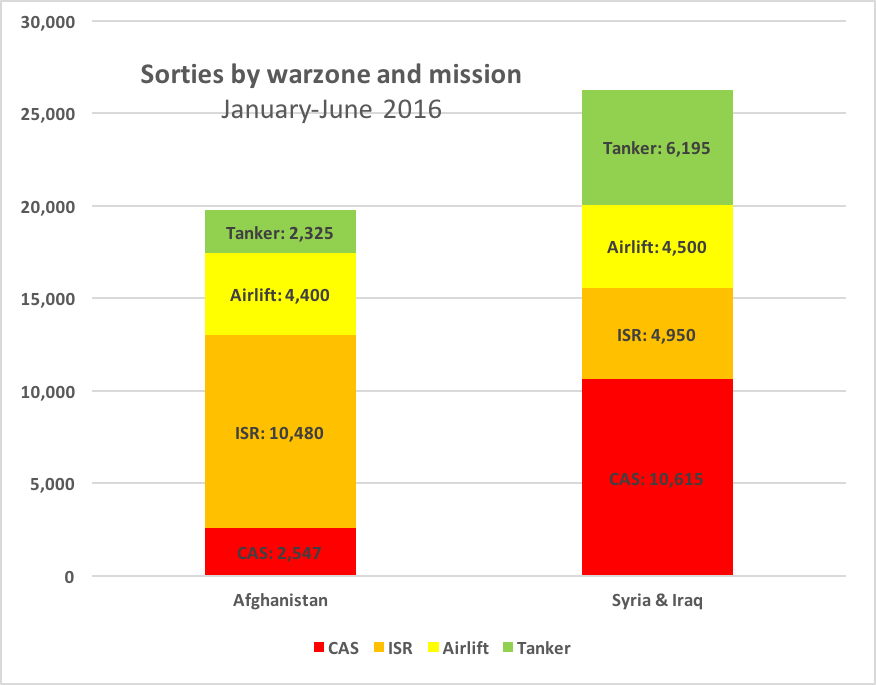

Instead of airstrikes, what US forces deliver to their Afghan colleagues is Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) — and lots of it. The data shows twice as many ISR flights a month over Afghanistan, on average, as there are over Syria and Iraq combined. Put another way, in Iraq and Syria there’s about one ISR flight for every two Close Air Support (CAS) mission; in Afghanistan, there’re four ISR flights for every one strike mission. Traditionally, the demand for targeting data to direct airstrikes is what drives most ISR demand; in Afghanistan, the demand is probably coming from Afghan ground troops instead.

One lesson from these figures: Demand for ISR doesn’t necessarily drop just because the airstrikes do. The constant demand for recon, year in and year out, has driven the Air Force drone community in particular close to the breaking point.

US CENTCOM data

Other unglamorous assets are also under strain. The two air campaigns required about 4,500 airlift flights apiece in the first six months of the year to move supplies to US and friendly forces.

Then there’s mid-air refueling from tankers, a fleet of aging workhorses that the Air Force is struggling to replace. With in-country bases increasingly rare, the US military’s relatively short-ranged fighters often can’t reach the target at all without a mid-mission top-up or two.

Afghanistan is infamous for needing tankers, because the country is so sprawling and so remote. Strike fighters flying off carriers in the Indian Ocean notoriously have to tank time and time again in a single sortie. But the number of tanker sorties in Afghanistan so far this year — just under 13 a day, on average — is less than half the number in Iraq and Afghanistan — over 34 per day. While aircraft operating over Afghanistan often have to fly farther, there are simply far more fuel-hungry fighters in the air over Syria and Iraq.

These broad-brush figures of course obscure important details, like the strain on the small but crucial fleet of AWACS airborne command posts. And data are ultimately a symptom of strategy, the fever line indicating the health of the patient, rather than the thing itself. For analysis on that front, we turned to one of America’s leading advocates of airpower.

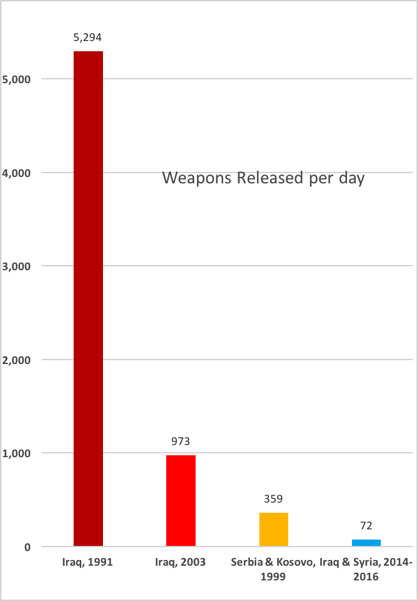

Data courtesy David Deptula, Mitchell Institute

An “Anemic” Air War in Syria?

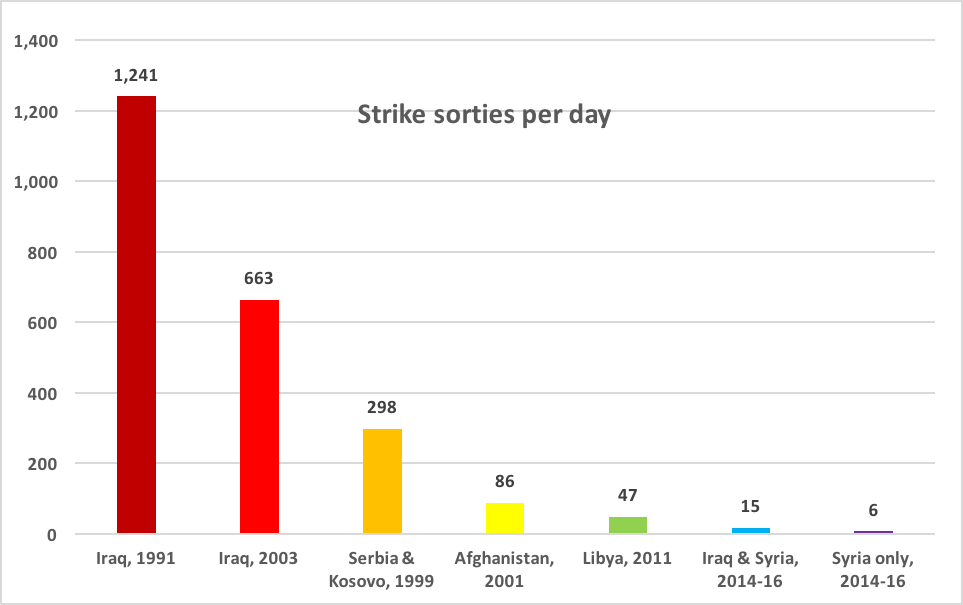

“It is somewhat promising that CENTCOM is increasing its level of effort against the Islamic State,” said David Deptula, a retired three-star general and F-15 fighter pilot, “(but) if you break out the strikes against the Islamic State in Syria versus the Islamic State in Iraq… you will find that the strikes against the Islamic State in Syria are what can only be described as anemic relative to previous air campaigns that were effective.”

By Deptula’s count, US airstrikes against Daesh overall have averaged 15 sorties a day, delivering 72 weapons among them: nine sorties against targets in Iraq, just six in Syria. That’s miniscule compared to the Desert Storm air campaign, which Deptula helped plan, which inflicted a staggering 1,241 strike sorties and 5,294 weapons a day. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was mere 663 strikes and 973 weapons a day, in part because the near-universal adoption of smart bombs allowed smaller bombardments. Even Operation Allied Force against Serbia in 1999 totaled 298 strike sorties and 359 weapons a day.

Data courtesy David Deptula, Mitchell Institute

Even within those 15 strike sorties a day, Deptula noted, there’s that imbalance between nine strikes in Iraq versus only six in Syria — the heart of the so-called Islamic State. Air power theory since Billy Mitchell and Giulio Douhet has always argued for striking the source of the enemy’s power at once, rather than grinding down his frontline forces first.

“The latest statistics indicate that the current Army-led (ground-centric) strategy is to secure the sovereignty of Iraq first, before decisively dealing with the Islamic State in Syria. This is precisely backwards,” said Deptula, now dean of the Mitchell Institute of Airpower Studies here in Washington. “The core US security interest in the region is to deny the Islamic State a sanctuary to export terrorism—not to act as a surrogate for Iraq’s military.”

The slow, grinding pace has given the Islamic State plenty of time to insinuate its influence in the West, “influence that has exhibited itself in the attacks in Orlando, Paris, Brussels, Nice, and more to come,” Deptula said.

“Two years ago, the US-led coalition should have put together a comprehensive strategy aimed to rapidly and effectively decompose the Islamic State as an operating system,” Deptula said, but it’s not too late to change course. “We must increase the current minuscule US average number of six strikes per day against the Islamic State in Syria to a number adequate to, and focused on a strategy designed to, rapidly crush each of the elements that make up the Islamic State.”

US CENTCOM data

Air Force picks Anduril, General Atomics for next round of CCA work

The two vendors emerged successful from an original pool of five and are expected to carry their drone designs through a prototyping phase that will build and test aircraft.