F/A-18F Super Hornet

NAVAL AIR STATION PATUXENT RIVER: So easy, a journalist can do it. That could be the slogan for the Navy’s new Magic Carpet software, which simplifies the most stressful task in aviation: landing on deck of an aircraft carrier.

I’d never pretend I could fly a real plane. But in a simulator, with Navy engineer Buddy Denham coaching me all the way, this near-sighted and uncoordinated reporter managed to land a virtual Super Hornet on a virtual carrier, three times in a row without breaking anything

Then I asked Denham to turn Magic Carpet off and let me try again. Suddenly, my every move went wild. When I banked to line up better with the carrier, I’d mess up my speed and my angle of descent. When I tried to fix speed, I’d mess up alignment and angle. When I tried to fix angle, I’d mess up alignment and speed. (Apologies to the real pilots for butchering their terminology). I’d still be struggling to correct my previous overcorrection when I spiraled straight up into the sky or down into the water.

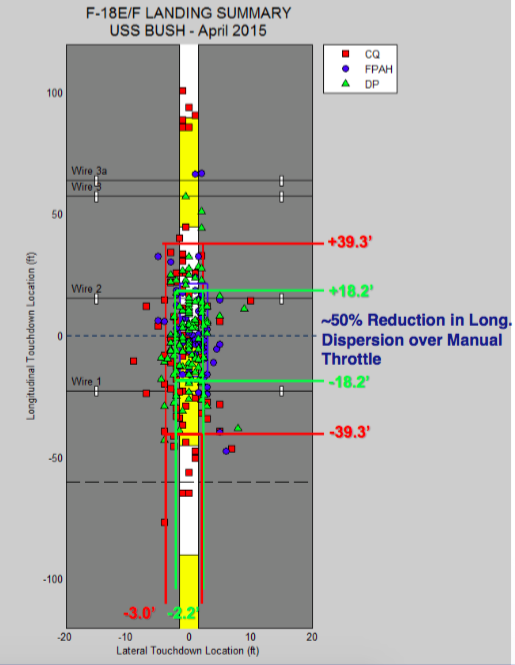

Test landings with Magic Carpet (green and blue dots) grouped more precisely and consistently on the targeted area of the deck than landings without (red dots).

I’m no pilot, but real pilots face the same problem; they just handle it better. To land on an airfield that’s not only short but in constant motion, you need to get everything just right, but everything you adjust affects everything else. As a result, carrier landings are so stressful, especially at night, that one physiological test showed Navy pilots were more stressed-out than troops in combat. Being able to land cleanly on the carrier is a mark of pride, and it consumes a tremendous amount of training time.

But things still go wrong, especially for newer pilots and for any pilot at the end of a long, exhausting sortie. No matter how proud a pilot is of his carrier landings, Denham said, “after an eight-hour combat mission over Iraq… the last thing I want to do is worry about landing on the ship.”

In keeping with Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work’s Third Offset philosophy of automation, Magic Carpet doesn’t replace humans — it helps them. It’s rather like the old saying about swans. They seem smooth and graceful as they swim, but below the surface there’s a great deal of frantic paddling. With Magic Carpet, the computer is doing that paddling, constantly making tiny adjustments — faster and more precisely than any human could manage — to keep the aircraft on the pilot’s desired course.

In a further birdlike touch, a Super Hornet using Magic Carpet constantly flexes its control surfaces, making the wing look like it’s rippling. “If you ever watch a bird,” said Denham, “he’s modulating lift… to decel(erate) and control which limb he’s going to grab onto…warping and changing the whole wing.” Such “Direct Lift Control” has been tried before, starting decades ago, but without automation, it often proved too complicated for human pilots to keep track of.

When Magic Carpet is switched on, the pilot no longer directly controls the flaps, throttle, and so on. Instead, he or she chooses a path and the computer makes the fine adjustments to get and stay on it. Affecting one aspect of flight — angle, speed, alignment, and so on — still affects the others, but the pilot can focus on one at a time while the computer keeps the others under control. The pilot remains a crucial part of the system.

Magic Carpet evolved out of efforts to improve the AV-8 Harrier, a jump jet notorious for killing its pilots. Some of that research spun out into the F-35B program — also a jump jet — and some to the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and its EA-18G Growler variant, Denham told reporters. (The Navy won’t invest in Magic Carpet for the older F/A-18A, B, C, & D Hornets, which are due for retirement).

The pace has been intense. The first demonstration aircraft flew in February 2015; a Navy test squadron did 181 landings on the carrier USS Bush in April 2015; and testers flew a second round on the USS George Washington in July of this year. The software will be made available to the fleet in September, and the first operational squadrons will start training with it in October.

Meanwhile the Navy is signing a contract with Boeing to develop a more refined version with quadruple redundancy to guard against failures. That enhanced Magic Carpet will go out in 2018-2019. At that point, Denham said, the software should be so reliable that the Navy could reduce or theoretically eliminate training on traditional landings.

Originally, the Navy planned to wait for the full-up, quadruple redundant 2018-2019 version of the Magic Carpet software before introducing it to the fleet. But so many senior leaders tried it out and got so excited about it, Denham said, that they pushed up the date so operational pilots could start learning how to work with Magic Carpet as soon as possible.

In the longer term, “it’s going to change how we fly airplanes across the board,” Denham said. “This is the final chapter in manned aviation, we’re doing it right now.”

The X-47 drone and a manned F/A-18 Super Hornet operating side by side on the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

That said, the Magic Carpet software was developed independently of the Navy’s carrier-based drone, the X-47, and the two approaches are very different. While the X-47B is obviously unmanned, it requires a human operator and specialized landing aids aboard the carrier. Magic Carpet requires a human pilot aboard the aircraft but needs no data or special help from the carrier.

Unlike the X-47 drone, the Magic Carpet software doesn’t know where the carrier is, just where the pilot wants to go. But once the pilot sets a course, the computer makes it vastly easier to stay on it — just ask this journalist.

Anduril debuts Pulsar AI-powered electronic warfare system

Company executives claimed the Pulsar system can use AI tools to quickly identify new threats and devise defenses against them, compressing the timeline for responding to rapidly-evolving electronic warfare.