Breaking Defense analysis of Central Command data

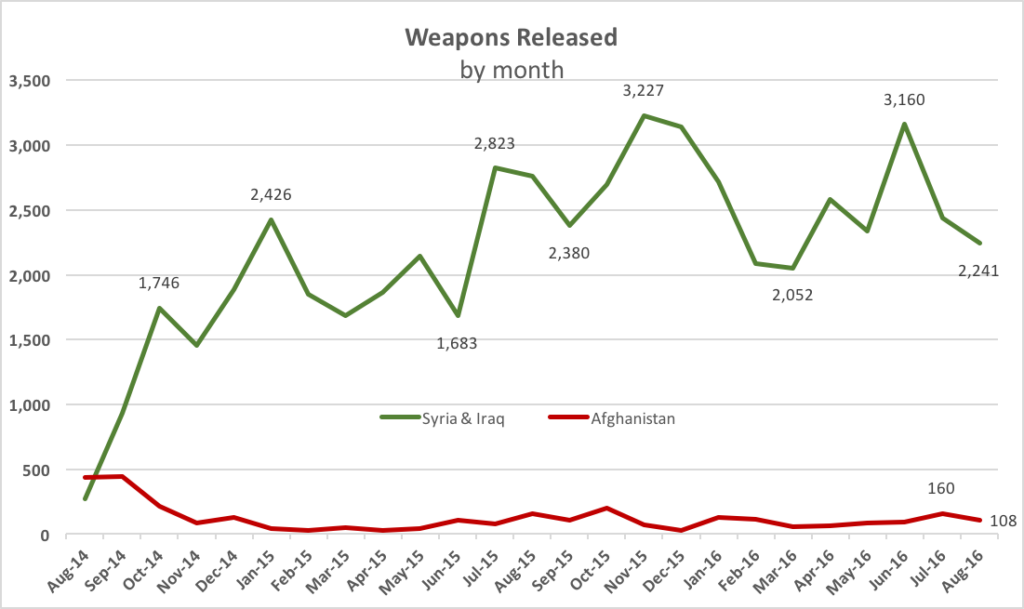

WASHINGTON: Airstrikes against the Islamic State have dropped 30 percent since June, because Islamic State retreats and Turkish advances have made it much harder to find targets, three experts told us. The administration’s self-imposed limits and negotiations with Russia — of which the military is very wary — restrict airstrikes as well.

The ground war in Iraq is currently between sieges, with Fallujah retaken in June and the battle to take Mosul not yet begun, and it’s air support to ground operations that have driven most of the strikes so far. There’s always an ebb and flow to conflict. But, said leading Mideast scholar Tony Cordesman, what’s happening now is “not just a lull.”

Breaking Defense analysis of Central Command data

As Daesh forces grow weaker and less aggressive, holing up in populated areas rather than advancing across the desert, it’s harder to find and bomb them. As Turkey carves out an enclave in northern Syria, less in order to fight Daesh than to preempt Kurdish gains, the most successful US-backed force in Syria — the Kurdish YPG — has to rein in its advances, so US airstrikes in support of YPG dial down as well.

“Turkey’s intervention has greatly complicated use of Kurdish rebels in Syria,” Cordesman told me. “Negotiations with Russia could suddenly change the bombing patterns in the west (of Syria) and against ISIS, and the ethnic and sectarian politics of who fights where on the ground have to be resolved going into Mosul.” Any of these events could change the nature of the war by itself, let alone all of them in combination.

“Strikes peak during active combat support of Arab and Kurdish ground forces or to check ISIS offensives,” said Cordesman. The battered Islamic State isn’t launching offensives any more, however. In Iraq, the various factions — Shia-dominated government, Shia militias, Arab militias, and Kurds — are wrangling over who takes what part of Mosul. In Syria, the Kurdish YPG has hit the brakes so they don’t run into the Turks, which has fought Kurds for generations before Daesh was ever dreamed of. As for the Turks, Cordesman noted, they’re a powerful modern army with little need for US air support.

The Turkish impact is “definitely mixed,” said Peter Haynes, a retired Navy captain now with the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. “It is a blessing in the short term, as far as moving ground troops into Syria to root out ISIS. But in the middle term, at least, it is far more mixed.”

“As the Turks push deeper into Syria, I would expect more incidents of Turkish forces essentially attempting to keep YPG forces at bay and restrict their movements,” Haynes said, “which would include artillery fire and perhaps airstrikes on YPG forces — some of which, it should be remembered, have US SOF (Special Operations Forces) embedded as advisors.”

F-15E takes off from Incirlik, Turkey

“All of this puts the United States in a precarious position,” Haynes said, caught between a crucial NATO ally and its most successful Syrian proxy, whose political goals are violently incompatible. Meanwhile, as Turks and Kurds stare warily at each other, Daesh has holed up in urban areas where it’s much harder to target — at least, as long as you’re concerned about civilian casualties, a consideration which doesn’t hinder Russia.

Avoiding collateral damage is not the only self-imposed limitation on the US air campaign. Airstrikes have focused on Daesh’s frontline fighters, especially those directly threatening US-backed forces on the ground. The ground war has ebbed of late because of intra-Iraqi politics and Kurdish-Turkish tensions.

Classic airpower theorists would argue that subordinating the air war to the ground war this way is a mistake. If airpower focused on strategic targets — hard as they might be to find with a part-state, part-guerilla organization like Daesh — you wouldn’t have the current lull in airstrikes.

“It’s a function of the operational approach that the administration has embraced, which is a focus on the Islamic State’s military arm, rather than the totality of the IS organization,” said retired Air Force Lt. Gen. David Deptula.

One of the chief architects of the 1991 air war against Saddam’s Iraq, Deptula has frequently critiqued the “anemic” campaign against the Islamic State for focusing too narrowly on supporting ground operations, especially in Iraq, at the expense of striking the terror group’s political and economic infrastructure, which is mostly in Syria. Under the current fighter-focused, Iraq-first approach, Deptula said, any drop in the number of enemy fighters on the battlefield — for example, because they retreated from Fallujah — means fewer targets and therefore fewer strikes. (You can read Central Command’s response to Deptula here).

Whether a different strategy could get the war unstuck is an open question. What is clear, with the air war still averaging almost 2,000 strikes a month after more than two years, is that the end is nowhere in sight.

Navy jet trainer fleet operations remain paused after engine mishap

One week after the incident, a Navy spokesperson says the service is continuing to assess the fleet’s ability to safely resume flight.