USS Ford

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB: The $13 billion supercarrier USS Ford and the $500 million Littoral Combat Ship are both suffering engine trouble. But Navy Secretary Ray Mabus took pains today to defend LCS even as he derided Ford as “a textbook example of how not to build a ship.”

Mabus’ determination to draw a distinction says a lot about his preferences and priorities, especially since much of his critique of Ford would apply equally well to LCS. Both programs originated in the era of Donald Rumsfeld’s “transformation,” after then-candidate George H.W. Bush had promised to skip a generation of technology.

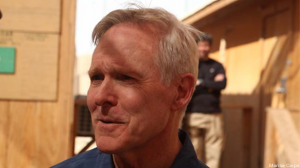

Ray Mabus

“The Ford is a textbook example of how not to build a ship,” Ford told reporters. “(We were) building it while it’s still being designed” — which results in costly do-overs of already-finished components — “(and) trying to force too much new and unproven technology on it” — whose teething troubles result in unplanned delays and costs.

“That was already on fire when I got in,” said Mabus, who became Navy Secretary the year the Ford’s keel was laid. “But we’ve stopped the cost growth.” The carrier’s schedule is still slipping, however, with a November delivery to the fleet postponed indefinitely due to problems in the Main Turbine Generators (MTG).

Meanwhile, however, five Littoral Combat Ships have suffered crippling breakdowns in 15 months. Isn’t LCS also a textbook example of a troubled ship program, I asked Mabus, for much the same reasons as Ford?

“No,” said Mabus. LCS is more an example of typical teething troubles on a new design, he argued.

“Every time you start a new class of ship…you’re going to have issues,” he said. “LCS gets a lot of attention, but during the first deployment of an LCS to Singapore…it was ready for sea more than the (US) Pacific Fleet average.”

“It’s got a lot of attention mainly because it looks different,” Mabus said. “It is a different kind of ship.”

LCS-2, USS Independence, followed by LCS-1, USS Freedom, showing the two different designs.

In fact, it’s two different kinds of ship. The LCS-1 Freedom class, built by Lockheed to a design inspired by racing yachts, and the LCS-2 Independence, which famously resembles Star Trek’s Klingon Bird of Prey, is built by Austal. Both variants have suffered breakdowns. Both, like Ford, combined multiple untested innovations in ways that greatly complicated their development: the unusual hulls, a high-speed propulsion system unlike anything else in the Navy, and an extremely small crew highly dependent on automation aboard ship and contractors ashore. There was even a last-minute decision to redesign the first ship of each type for greater resistance to battle damage, requiring expensive refits when they were already half-built.

So LCS’s agonies strongly resemble the Ford’s. The crucial mistakes on both ships also predated Mabus’s appointment. “The main issue I had to deal with when I got there was they were just costing way too much, and we’ve driven that down,” Mabus said of LCS.

Why do two programs with similar troubles get such a different reaction from Mabus? It’s especially striking because the carrier program matters much more to naval traditionalists, who often disdain the relatively tiny and lightly armed LCS. But throughout Mabus’s seven years in office — the longest tenure of a Navy Secretary since World War I — he’s measured his success in terms of numbers of ships.

From 2001 to 2008, Mabus said today (as he says in every speech he makes) the US Navy fell from 316 ships to 278 and put only 41 new ships on contract. In the seven years since 2009, Mabus has contracted for 86.

“Quantity has a quality all of its own,” Mabus said — and you don’t get quantity without a small ship cheap enough to build in bulk. In the face of two skeptical Defense Secretaries and sometimes bitter criticism from Congress, Mabus’s commitment to LCS explains a lot about its survival.

On current plans, Mabus said, the Navy will reach 300 ships by 2019 and 308 by 2021. 308 is the current official requirement, but the Navy’s currently reassessing — and almost certainly raising — that number in light of growing Russian and Chinese threats.

“308…is what we’ve been building to,” Mabus said. “We are undergoing a force structure assessment right now. The CNO (Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson) said during hearings last year that he would bet a paycheck that the number as going up. I’m happy to bet the CNO’s paycheck too.

“Going forward whatever that force structure assessment is, that’s what we’ll have to build for,” Mabus said.

That will be after President Obama and, presumably, most of his officials depart. But the long time scales for developing and building a class of ships don’t respect political deadlines, Mabus made clear.

“Building ships is not the job of one administration, not the job of one secretary. If you miss a year you never get it back,” He said. “And it’s taken from 2009 until 2021 just to reverse it and get it back up to where we thought we needed to be — and we’re pretty much at the capacity of our shipyards now.”

‘Mind-boggling’: Israel, Ukraine are mere previews of a much larger Pacific missile war, officials warn

MDA Chief Lt. Gen. Heath Collins said more maneuverable missiles and drones have changed the missile defense game: Instead of just preparing to hit “fastballs,” he said, “now we’re hitting sliders and curveballs.”