F-35A at 2017 Paris Air Show

CAPITOL HILL: Stealth was sold as something close to magic when it first appeared. And, as usually happens when extraordinary claims are made, the blowback was intense. Skeptics pointed to its vulnerability to large-scale, land-based radars, to the fact it wasn’t invisible to the naked eye, to the costs and difficulties of maintaining the expensive coatings, and the staggering overall cost of some of the aircraft (see B-2).

This morning, the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute rolled out a report on stealth that should put many of those criticisms to bed. The study argues simply that America’s fighters, bombers and, probably, airborne tankers need stealth to remain effective and to perform well against increasingly sophisticated ground- and air-based missile threats.

B-21 Raider artist rendering

In the reasoned language of the report: “Stealth, or aircraft signature reduction, is a potent and viable military capability in modern combat, and will remain so well into the future. It is not, however, an all or nothing capability, as some critiques have suggested.”

So stealth ain’t magic, but it’s absolutely necessary, the report’s authors say. Why? Stealth “significantly reduces the range at which aircraft can be detected, and this in turn increases survivability. Stealth combined with speed creates additional challenges for enemy air defenders. (See F-22) Even if defenders can detect the presence of aircraft, the time they have to track, fire, and guide surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) is minimal. Sometimes engagement windows are so short, even detected stealth aircraft are nearly impossible to engage.”

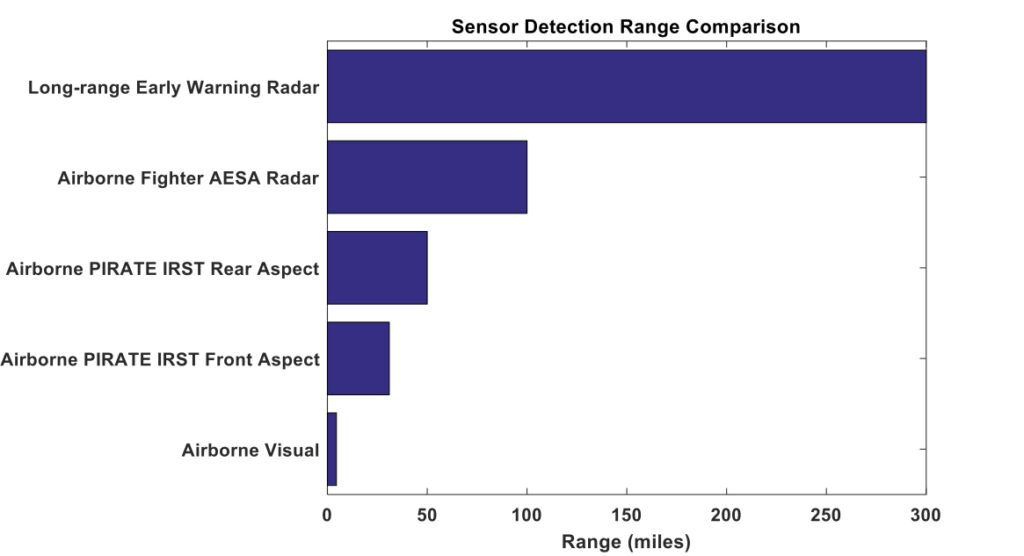

They’ve got a handy chart to illustrate the basics of detection of an aircraft:

For perspective, the visual range detection is three miles — in perfect weather.

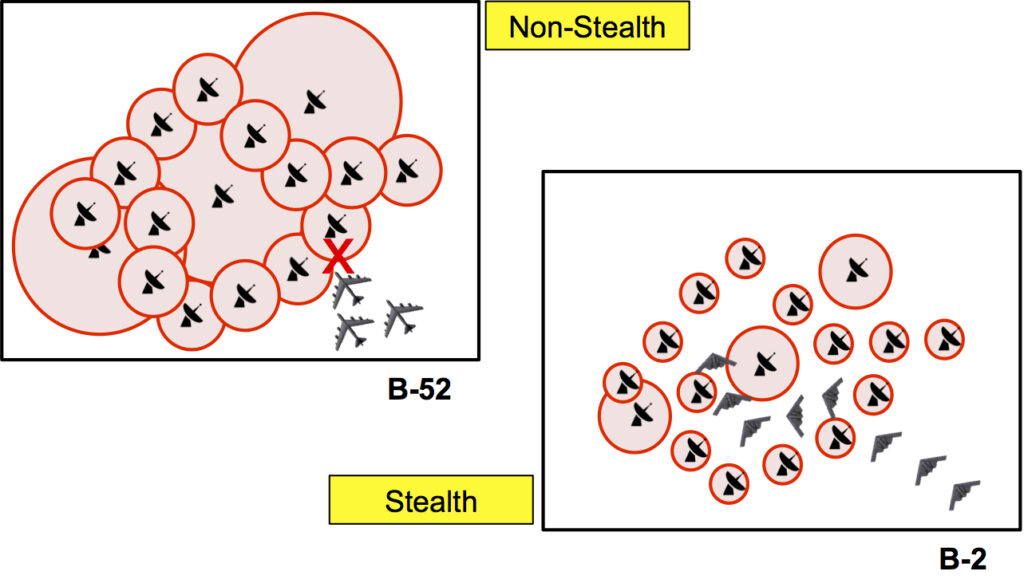

And the smaller a plane’s radar cross-section is — thanks to stealth — the harder it is to spot with certainty. That means an enemy must build a much denser air defense system to ensure having a decent chance to stop US warplanes. How dense? Check out the chart below.

North Korea air defenses

In an interview I did three years ago with Gen. Mike Hostage, I wrote that what marks the F-35 as a dominant weapon is its combination of stealth, computing power, built-in targeting and databases and sensors. All of that information is fed to the pilot through his helmet with automatically-generated target, weapons and route choices. Those route choices, based on intelligence, are extremely important to an aircraft’s ability to penetrate the enemy’s defenses.

This chart, presented at the AFA event here this morning, illustrates how stealth aircraft are able to pick their way through an enemy’s air defenses.

Even with designed-in stealth (rounded edges, cooled air and masked inlets and coatings) aircraft need to manage their spectrum. AESA radar and electronic warfare tools on aircraft like the F-35 can help mask the plane further. Add in cyber warfare and electromagnetic spoofing — feeding erroneous information to enemy sensors — and you’ve got a pretty lethal combination.

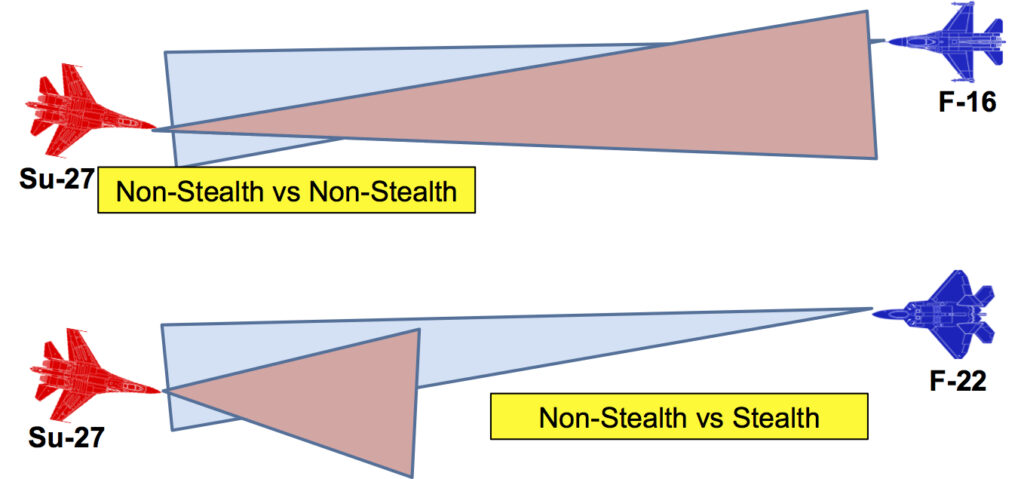

As retired Maj. Gen. Mark Barrett, one of the report’s two authors. told the audience of about 100, “stealth still gives us a fighting chance.” Barrett, a former F-22 pilot and now vice president of consulting firm Operational Support Group, added that the overall cost of stealthy aircraft is “relatively low” for the simple reason that they can penetrate an enemy’s defenses more effectively than fourth generation aircraft, especially when you talk about the B-2 bomber fleet. Check out this chart:

As an illustration of how stealth improves the odds of a fighter taking out an enemy — Hostage and other combat pilots call it getting inside the kill chain — you can also check this chart. The F-16 and Russian Su-27 pretty much detect each other at the same distance. The F-22, in this unclassified illustration, boasts an enormous advantage because its stealth makes it much harder to detect head on. (All planes with tails can be detected fairly well from the side.) It can detect the other aircraft from a much greater distance allowing it a much higher probability to kill the opposing pilot.

But the study’s authors pose the correct question: “Will stealth remain viable in future decades in the face of these technologies, or will its effectiveness wane? Should the United States continue to invest in stealth systems to improve them or mitigate technology that attempts to counter them, or shift its approach? Debate over these issues will increase in the coming years as spending on systems such as the F-35 and B-21 increases.”

Their conclusion is that, yes, stealth is absolutely needed but does not exist on its own. But it is important Barrett said during this morning’s presentation that he thinks recent discussion of building a stealthy airborne tanker is on the right track because of the tyrannies of distance in the Pacific theater. Of course, they’d have to figure out how to build a stealthy boom.

Navy jet trainer fleet operations remain paused after engine mishap

One week after the incident, a Navy spokesperson says the service is continuing to assess the fleet’s ability to safely resume flight.