The two variants of the Navy Littoral Combat Ship — LCS-1 Freedom and LCS-2 Independence – side by side off the California coast.

Yes, the Navy has cut short its Littoral Combat Ship program and started work on a bigger, tougher, better-armed frigate. But the small ships will still be big part of the future fleet, experts we spoke to agreed, and the frigate will carry on much of the LCS legacy.

It’s true the Navy’s needs have changed, because the world has changed, with rising threats from major powers eclipsing Third World pirates – but the Littoral Combat Ship has changed as well. In particular, an LCS design conceived during the days of the “peace dividend” is being upgunned with both short- and long-range missiles that increase its relevance for major war.

The shift to frigates is not just a rejection of LCS, either. While the frigate concept turns away from some aspects of LCS – its high speed, its small crew, its limited combat power – it embraces others, such as extending the ship’s reach with unmanned craft and fleetwide networks. In other crucial respects, especially the frigate’s offensive and defensive firepower, the Navy’s still making up its mind.

The Cyclone-class patrol craft USS Sirocco.

After studying the Navy’s Request For Information (RFI) on industry’s frigate designs, “I wouldn’t say the RFI repudiates the LCS approach, because the idea of having a smaller, less-expensive, shallow-draft, fast ship makes sense,” said retired commander Bryan Clark, now with the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. The new frigate isn’t really replacing the 3,400-ton LCS, he argued, but filling a gap between smaller coastal patrol craft like the 380-ton Cyclone class and larger multi-role warships like 9,700-ton Aegis destroyers.

To that end, Clark wants the future frigate to have both the weapons and radar to conduct wide-area air defense of nearby ships in a task force or convoy –a mini-Aegis like Spain’s Navantia frigates – rather than only defend itself – like the current LCS.

That kind of capability would of course, increase the frigate’s price, perhaps dramatically, which is why the original Small Surface Combatant Task Force from 2014 decided against it.

“The SSCTF said the knee in the curve, from the cost perspective, is when you add area air defense, (i.e.) when you’re defending someone else. For that, you need a different weapon, you need different sensors,” a retired Naval officer told me. “You’re adding hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Instead, the task force proposed a host of other, more affordable improvements to the existing LCS designs.

By giving up minesweeping capability, the 11-meter rigid-hulled inflatable boats (RHIBs), and associated equipment, the task force managed to fit a lot of new equipment into the LCS hull. “The last frigate design had 30 mm guns, surface-to-surface missiles — the Hellfires — over the horizon missiles, the 76 mm gun, anti-submarine torpedoes, a helicopter,” the naval officer said. “That’s a very capable ship.”

So does the Navy want an upgraded version of the current LCS, or a new, larger frigate with the weapons and sensors for area air defense? The current Request For Information carefully leaves that crucial question open, for now.

Austal’s proposal for an LCS frigate with Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes.

Missile Sponges & Network Nodes

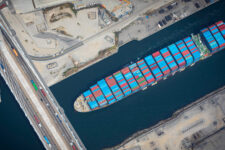

Whatever the final shape of the frigates, Littoral Combat Ships can play important supporting roles alongside them in major wars, and a leading role in low-threat theaters. In what passes for peacetime conditions in our troubled world, LCS will hunt pirates and drug-runners, exercise with friendly navies, and patrol waters too shallow for other ships. They will also be the Navy’s only minesweepers once the aging and much more vulnerable Avenger class retires, and mines are favorite weapons of Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran.

Of the two LCS variants, the broad-decked trimaran Independence and the sleeker Freedom, said retired Navy Captain Jerry Hendrix, “I see the Independence class focusing on mine warfare and Freedom class doing littoral (coastal) surface warfare. The new frigate will do ASW/ASUW (anti-submarine/anti-surface warfare) in blue water as well as carrier strike group and alliance convoy escort duty.”

In high-tech conflict, LCS lacks the anti-missile defenses and damage-resistant hull of larger vessels like destroyers – and possibly the frigate, depending on the Navy’s final choice – but it can operate under the Aegis (literally) of larger ships. With that protection, LCS can serve the fleet as extra eyes, ears, and missile launchers.

A Perry-class frigate, USS Vandegrift

Adding the upgunned LCS to the battle line complicates the enemy’s problem by multiplying both threats and targets, a concept the the Navy calls distributed lethality. True, as Littoral Combat Ships take hits, they may well sink or retreat to port for repairs while a larger ship could keep on fighting, but better a LCS eat a missile than a larger and more valuable vessel.

That sounds cold-blooded, but it’s an honorable Navy tradition. The practice dates back at least to World War II, when over-enthusiastic kamikaze pilots often dove at the first picket ship they saw rather than waiting until they reached the aircraft carriers. The Cold War’s Perry-class frigates, only retired in 2015, were known with grim humor as “missile sponges.”

“The whole idea of distributed lethality is not to put all your eggs in one basket and distribute your firepower over multiple platforms, so in case you lose one, you don’t lose your whole capability,” said Steven Wills, a retired Navy officer who served on Perry frigates, as well as other often-neglected smaller vessels like minesweepers and coastal patrol craft.

What modern technology adds to the old missile sponge idea is networking. Instead of just sending a radio warning of an incoming attack, the picket ships can share detailed targeting data. An LCS or frigate that’s fired all its own missiles can still tell other ships where to shoot. A ship whose own sensors can’t pick up a particular target can still fire based on data from another vessel that’s better placed or better equipped.

The LCS Coronado test-fires a new anti-ship missile from Norway’s Kongsberg.

Networking this way empowers large numbers of small ships in new ways. The old axiom is “quantity has a quality all its own,” but you have to update that for the information age, when Metcalfe’s Law states a network’s power grows exponentially as it adds more nodes. At least in theory every ship, small or large, that’s added to a networked fleet increases the combat effectiveness of every other ship. Conversely, any node in the network can call on the full sensor- and firepower of the entire fleet, making even a small ship like LCS a big potential threat.

In fact, Bryan Clark and his CSBA colleagues argue the LCS’s flaw is it’s too large. (Ironically, the original concept for LCS, called Streetfighter, was much smaller). They call LCS an unhappy compromise between a smaller, more agile, and more affordable coastal patrol craft like the Cyclones and a larger, more capable, and more expensive guided-missile frigate (FFG).

“It tried to do the patrol ship job and the FFG job,” Clark told me. “The problem was LCS was not inexpensive enough to be affordable in large numbers … and lacked the organic capabilities to fight and survive in contested operating environments.” That said, Clark continued, LCS can fill the gap until we build sufficient numbers of both smaller patrol ships – his model here is Sweden’s 600-ton Visby corvettes – and larger frigates.

Lockheed has proposed larger variants of the LCS, including ones with VLS, for foreign markets.

The LCS Legacy

In many ways, the frigate plan is a return to traditional naval virtues. It will likely be larger than LCS, which lets it both carry more equipment and take more damage. It will be capable of conducting multiple missions at once: defending against surface ships, submarines, and possibly air attack. By contrast, LCS can do one mission at a time, depending on which plug-and-play mission module is installed – a concept the Navy always struggled with.

“There’s a bit of a collective sigh, ‘oh good we don’t have to have swap-in swap-out modules,'” a DC-based naval analyst told me. “The frigate’s a multi-mission small ship; it’s a traditional way of doing business. We’re comfortable with things called frigates. We didn’t know what to do with this LCS.”

“We changed so many things at the same time,” said the naval officer. “The entire surface enterprise — the budgeting people, the manning people, the training people — all had to make significant changes to the way they did business.” Like other other weapons programs of the “transformation” era in the early 2000s — the Army’s Future Combat System, the Coast Guard’s Deepwater Project — LCS tried to revolutionize too many aspects of warfare at once.

That said, a lot of LCS lives on in the frigate. Counting the bullet points in a Navy briefing to industry on the frigate, four of five top-priority characteristics are similar to LCS:

- conduct both anti-ship and anti-submarine warfare;

- extend the fleets’ sensor network;

- operate as a mothership for unmanned craft; and

- take on less demanding missions to free up destroyers.

Unlike LCS, however, the frigate must operate independently in high-threat environments – the fifth required characteristic – rather than depending on an Aegis destroyer escort for air and missile defense.

FFG(X) Industry Day Brief FINAL by BreakingDefense on Scribd

The frigate will also use the same manning scheme eventually adopted on LCS. Unlike traditional vessels, each frigate will have two crews, operating it in alternation, to allow it to spend more time deployed and less in port. On the other hand, the frigate will have a larger crew than LCS and use standard Navy systems wherever possible, both measures to avoid LCS’s chronic problems with maintenance. And the frigate won’t have to match the 40-plus-knot speed of LCS, a requirement that drove the LCS program to costly, oversized propulsion plants and exotic hull designs.

Perhaps the most basic thing LCS and the frigate have in common is the simple fact they’re both small ships – a category the Navy has often neglected. Focused on aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers, traditionalists often disparaged LCS as the “little f****ing ship” for its fragility and lack of firepower. When the Navy brainstormed the “Surface Combatant 21” family of ships in the 1990s, Wills recalled, “some of the Navy did not even want to include a small surface combatant” to replace the aging Perry frigates. If LCS has done just one good deed for the Navy, it’s been to cement small warships’ place in the fleet – and in the budget.

The Navy’s never-ending quest for 355 ships: 5 Navy stories from 2024

Ship counts were clearly on the mind of US Navy officials this year as they made numerous plays to bolster the fleet in novel ways.