South Dakota National Guard soldiers on duty in Afghanistan.

The battle between the regular Army and the National Guard, which we all knew would blow up one of these days, has blown up. At 3:30 this afternoon, the spokesman of the 54 state and territorial Guard commanders, Kentucky Adjutant General Ed Tonini, raised the standard of revolt against the active-duty leadership who had, he said, “slammed their minds shut” on any compromise. Meanwhile, much more quietly, and with many caveats, the regulars have broken a 13-year taboo: In an exclusive interview with Breaking Defense, Army Quadrennial Defense Review director Maj. Gen. John Rossi questioned aspects of the Guard’s much-lauded combat performance since 9/11.

Army leaders from Chief of Staff Ray Odierno on down have long argued that troops who train part-time can’t mobilize fast enough for the short-notice, high-complexity conflicts expected in the future. But this is the first time a senior active-duty general has said, to my knowledge, that the proof of this argument is that Guard combat brigades were rarely assigned the most demanding missions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

What Rossi said is far more nuanced than the statement from Guard partisans. Maj. Gen. Tonini declared the Army leaders’ discussions with governors and Guard leaders “have been merely for show.” Retired Maj. Gen. Gus Hargett, head of the independent National Guard Association of the US, has called Odierno’s remarks “disparag[ing], disrespectful and simply not true.” But with over 700 Guardsmen and women killed in the line of duty since 2001, putting any kind of asterisk next to the Guard’s wartime record is potentially inflammatory. It marks a major escalation in what Army leaders are willing to say. But they also have a point.

“We have to be careful that….we don’t walk away with the wrong lessons,” Rossi told me. “Work hand in hand? Yes. Work side by side? Yes. Interchangeable? The answer on that is no.

“Army National Guard BCTs [brigade combat teams] are in fact interchangeable. They were very deliberately designed to be,” countered the former director of the National Guard Bureau, retired Lt. Gen. Steven Blum, when I summarized Rossi’s arguments for him in an email. “Drawing distinctions between the components, during times of constrained resources, only serves to damage all of our total force Army components and tarnish a proud institution.”

Rossi took pains to emphasize he wasn’t casting aspersions on the service of any individual Guard soldier. “Regular, Reserve, and Guard are all professionals,” Rossi told me. “This is not about individuals[:] This is about team practice.”

All three components train to the same standards for individuals and small units, Rossi said. But the part-time nature of Guard service and the scattered locations of Guard units make it much harder for them to train together as full brigades, he said: “These are big teams — 4,000, 5,000 person teams — that require, as a necessity, a lot of team practice.”

So in Iraq and Afghanistan, Guard and for that matter Army Reserve forces were typically used in smaller units such as companies (roughly 100-200 strong) under the command of active-duty headquarters. When Guard troops were used as full brigades, Rossi went on, they were typically given missions requiring less complex brigade-level coordination and planning. They secured roads and bases against attack, they advised and trained local forces, but they rarely conducted full-scale counterinsurgency operations combining intelligence gathering, combat, and hearts-and-minds campaigns in specific populated areas they “owned.”

These missions are “all important, all very dangerous,” Rossi said, “but some [are] more complex than others.” And a future fight against a better-armed, better-organized, and faster-maneuvering enemy will be more complex.

“You know, I just think you’re being hypocritical when you use those things against us when we did what we were asked to do,” said NGAUS chief Gus Hargett, a former Tennessee National Guard commander (aka “adjutant general”).In fact, Hargett told me this in an exclusive interview in February, back when the regulars were still keeping their questions about Guard performance off the record.

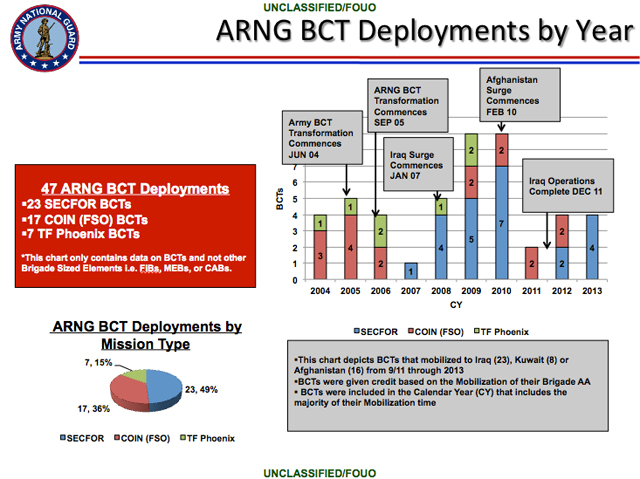

It’s true that most Guard brigades did advise-and-train or “security force” missions, not counterinsurgency missions in all their complexity — although a leaked slide shows a third of Guard combat brigades did do COIN, mostly towards the beginning of the war:

Most Army National Guard brigades deployed for less tactically complex — but still dangerous — missions such as convoy security and training Afghan forces (e.g. “Task Force Phoenix”), not full-scale counterinsurgency.

But, as former Guard Bureau chief Blum noted, “units do not get to select their mission assignments.”

Indeed, at least some Guard commanders wanted the most demanding missions. “At the time, I had a discussion with Gen. [David] Petraeus,” NGAUS’s Hargett recalled. “I said to him then, I don’t like the SECFOR [security force mission]. Brigades should be given space to manage, and I said this will one day be used against us.'”

Rossi acknowledged that it’s by no means impossible to train a Guard brigade to the same standard as an active-duty one: It just takes time — time the Army may not have in a future crisis.

“This is not looking at redoing OIF and OEF on the predictable ARFORGEN [Army force generation,” Rossi told me. “What would it take from a no-notice cold start?”

The current National Guard Bureau director, Gen. Frank Grass, has said that the time to get Guard brigades trained up for Afghanistan and Iraq dropped to 100-150 days, though if his training budget weren’t being cut he could get it down to 50 to 80 days.

But that’s for counterinsurgency missions. “[If] you set a goal of combined arms maneuver proficiency for a brigade,” said Rossi, “it has to take longer because… there’s additional training steps to give you the practice to get to that level of proficiency.”

Even regular army units are still struggling to relearn those “combined arms maneuver” skills — what most of us would recognize as conventional war — after years of operating from fixed bases against lightly armed guerrillas. In fact, Rossi admitted, budget cuts mean that for the next few years most regular troops won’t get to train in full-brigade operations, either.

“In the near term, we have some readiness challenges, up until ’19,” Rossi said. “But I want to get out past ’19, because that’s what we’re talking about, is the future…when the size of the force matches the money you have to train it.” At that hoped-for point, every remaining active-duty combat brigade will be going to a Combat Training Center for full-brigade wargames every other year. Guard brigades will be funded to reach company-level readiness one year in every five.

Of course, that is the Army’s plan. Guard advocates would argue the nation can get a lot more readiness out of citizen-soldiers for an affordable price. And, in Maj. Gen. Tonini’s words, “the fiscal 2015 Pentagon budget process has now officially shifted to where the Army National Guard value and proven capabilities can finally get a fair hearing – the Halls of Congress.” Regular Army advocates would suggest the Hill is outright tilted against them.

Just like the last time we had this fight, during the bitterly debated drawdown of the 1990s, the right balance between the active-duty Army and the Guard is now a matter for Congress to decide — and for the next war to pass bloody judgment on our decisions.

‘AI-BOM’ bombs: Army backs off, will demand less detailed data from AI vendors

Instead of demanding an exhaustive “AI Bill of Materials.” the Army will only ask contractors for a “baseball card” of key stats on their AI — while building up its in-house capacity to check for bad code or “poisoned” data.