A Radio Battalion marine parachutes in an exercise.

WASHINGTON: With the rise of high-tech threats from Russia and China, the Marine Corps plans a major increase in its forces devoted to jamming, hacking, and deceiving enemies. That includes:

- putting new sensors and jammers in everything from ground units to drones to V-22 Osprey tiltrotors and KC-130 transports, despite a tight budget;

- adding 1,000 to 3,000 more personnel, carved out of other parts of a Marine Corps legally limited to 182,000 active-duty troops. (That’s on top of a 1,300-plus increase in these specialties over the last several years);

- retraining skilled electronic warriors from disbanded EA-6B Prowler squadrons to work with ground units and drones;

- consolidating disparate disciplines — from offensive cyber warfare and electronic warfare to psychological operations and military deception — into a new “information warfare” force.

Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh

The changes are part of a top-to-bottom overview of the Marine Corps ordered by Commandant Gen. Robert Neller. That “Marine Corps Force 2025” review is ongoing, with two teams of 100 Marines now developing two alternative courses of action — one “evolutionary” and one “revolutionary” — that will be briefed to Neller in April, his deputy, Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh, said yesterday at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. A revision of the Marines’ “Expeditionary Force 21” concept for amphibious operations will come out in May, Walsh said, in time for the Navy League’s Sea-Air-Space conference.

Crucial details remain unresolved, such as whether the new information warfare forces will be permanent parts of Marine Expeditionary Units — which improves coordination with regular combat forces — or assigned as-needed for specific deployments — which makes it easier to do the highly specialized training that cyber and electronic warfare require. What is clear, however, is that the new approach will generally be more decentralized than the old, distributing capabilities widely across the force.

EA-6B Prowler

From Prowlers To “Every Airplane”

Historically, the face of Marine Corps and Navy electronic warfare was the EA-6B Prowler jamming aircraft. But Prowlers spent much of the post-9/11 era supporting other services — particularly the Army, which had disbanded its EW units in the 1990s. And now the aging aircraft will all be gone by 2019.

While the Navy is replacing its Prowlers roughly one-for-one with equally specialized EA-18 Growlers, the Marines aren’t buying a new electronic warfare aircraft. The new F-35B Joint Strike Fighter has much-touted (and highly classified) cyber/EW capabilities, but “it is not the replacement,” said Lt. Col. Jeff Kawada, the Marines’ branch chief for EW and offensive cyber. “It is one of the pillars.”

Instead of putting all their electronic warfare eggs in one flying basket, the Marines are putting EW pods on “every airplane that the Marine Corps flies,” said Kawada, a former Prowler crewman himself. “Unlike the Prowlers” — which tended to get called away on non-Marine missions — “this is an organic Marine Corps capability,” he said. Now EW will be available to Marine Expeditionary Unit commanders as long as they have any aircraft flying, manned or unmanned.

The Marines’ standard electronic warfare pod, called “Intrepid Tiger II,” first entered service in 2012. It has already flown on the F-18 Hornet fighter, AV-8B Harrier jump-jet, UH-1 Huey utility helicopter, and the RQ-7B Shadow drone, Kawada told me in a March interview. It’s scheduled to go on the AH-1Z Cobra attack helicopter, CH-53 heavy lift helicopter, V-22 Osprey tiltrotor, and even the KC-130 transport/fuel tanker.

Electronic warfare pods on a lumbering KC-130? It makes sense, said Walsh. The Marines already put sensors and smart bombs on KC-130s — the “Harvest Hawk” upgrade — to provide close air support to troops in Afghanistan. A KC-130 is slower than a fighter jet, of course, and it can’t survive in hostile airspace, but it has the fuel capacity and fuel efficiency to stay overhead much longer.

KC-130s, “they’re long-dwell, long-endurance, long-range,” Walsh told reporters after his CSIS talk. “We’re going to keep putting more packages on those things.”

In addition to jamming pods, the Marines are very interested in putting signals intelligence packages on a wide range of manned and unmanned aircraft. After all, you have to detect the enemy’s transmissions before you can jam them — and you have to understand your own emissions before you can defend them against enemy jamming. In a recent exercise, said Walsh, the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit had great success with RQ-21 Blackjack drones carrying the awesomely named “Spectral Bat” signals intelligence package.

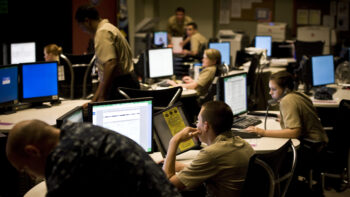

The Marines aren’t neglecting ground-based EW, either. Historically, that capability was concentrated in three Radio Battalions, which excel at both signals intelligence and electronic warfare. Like their flying comrades in the Prowler squadrons, the Radio Battalion troops tended to get pulled away on non-Marine missions, such as providing SIGINT support to special operations. (Locating terrorists by their cellphone transmissions has become a fine art). Now the Marine Corps is trying to reintegrate the Radio Battalions into its own operations. It’s also upgrading the battalions’ standard jammer, the Communications Emitter Sensing and Attack System (CESAS), to a CESAS II model.

An “Intrepid Tiger II” jamming pod on an F-18 Hornet

Putting Together The Pieces

Having a wide range of electronic warfare and signals intelligence gear on the ground, on drones, and on manned aircraft will give the Marines a much more versatile capability — and one much more resistant to battle damage — than investing in a silver bullet system. But someone has to take all the disparate pieces and get them to work together.

Marine Expeditionary Units already deploy with Cyber/Electronic Warfare Coordination Cells (CEWCCs). Like the Army, the Marines see cyber and EW as two sides of the same coin, two different ways to attack and defend the wireless networks on which modern militaries depend. But now the Marines want to bring in other disciplines as well.

“We are taking all the different pieces,” said Walsh, “whether it’s command and control, cyber, electronic warfare, psyops, information ops, and military deception — [many] different pieces, some very small but we’re going to grow them — and bringing them together in some kind of Information Warfare Group.”

The Marine Corps Information Operations Center at Quantico is a first attempt at putting all these pieces together, said Walsh, “but what we’re seeing is, as we deploy small teams out from there, it’s not going to be enough capacity.” It’s become clear you can’t centralize information operations forces for the entire Marine Corps in one place, he said.

But how far do you decentralize? It depends on the function, Walsh said. Offensive cyber operations, for example, require high-level authorization and would have to be centralized. Electronic warfare, signals intelligence, and defensive cyber could be permanently assigned to a division, brigade, or even in some cases an individual battalion.

“That’s the big thing I think we’re struggling with,” Walsh told reporters. “What capability do you need at what [level]?”

A soldier from the Army’s offensive cyber brigade during an exercise at Fort Lewis

Helping Out The Army

Watching the Marine Corps with some envy is the US Army, which disbanded its electronic warfare capabilities in the 1990s — although not its signals intelligence — and is now struggling to rebuild them.

“They’re ahead of us [because] the Marine Corps never got out of the electronic warfare business,” said Col. Jeffrey Church, the director of EW on the Army’s Pentagon staff (Section G-3/5/7). So why doesn’t the Army just buy Marine Corps EW gear? There’s tremendous institutional inertia in the way, Church said bluntly.

“We always go back to this one, ‘well, their requirements are different from our requirements,'” Church told me . “Yeah, yeah, yeah. The spectrum works the same for the Marines as it does for the Army. The adversary’s capabilities are no different for the Marines than they are for the Army.”

The two services do hold regular EW “synergy” meetings several times a year, said Church and Kawada. “We’re seeing there are a lot of places where we can collaborate…to develop joint products, joint capabilities,” Kawada said.

The two services may experiment with Marine EW payloads on Army helicopters, for example. The Marines are also interested in the Army’s future jammer, the Multi-Functional Electronic Warfare (MFEW) program. But collaboration is more likely on to be on the level of ensuring “baseline architecture” is compatible and can share data, rather than co-developing entire systems, Kawada said. “It makes sense for us to build separate capabilities, but then come together at a higher layer.”

Army halted weapon development and pushed tech to soldiers faster: 2024 in review

The Army spent 2024 pushing its new “transformation in contact” initiative while also pivoting away from several key weapon development initiatives.