M1 Abrams tanks of the 1st Cavalry Division fire during a NATO Atlantic Resolve exercise in Latvia.

UPDATED with Army clarification CAPITOL HILL: The Army will choose the four-star chief of its new Futures Command in “two or three weeks,” Secretary Mark Esper told reporters this morning after a Senate hearing. A location for the (fairly small) headquarters will follow, with the service honing its list of 30 cities to 10-12 this coming week but not announcing the final site until “late June,” Esper said.

Mark Esper

But Army Futures Command is just a means to an end: modernizing the Army for high-intensity war against Russia or China. That includes replacing the iconic but aging M1 Abrams main battle tank, as well as other war machines, with an all-new Next Generation Combat Vehicle optimized for urban warfare, Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley told the Senate Armed Services Committee.

In fact, Milley seemed to get out in front of Secretary Esper, who spoke only about replacing the M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, a tanklike troop carrier. Normally in lockstep, the two men described very different objectives for NGCV. It’s possible they’re just talking about different phases of a single overarching strategy.

UPDATE That’s exactly what they were doing, an Army official told me after this story originally posted: The Next Generation Combat Vehicle initiative will replace the Bradley first, as the most urgent matter, but NGCV will go on to replace other vehicles, including the tank. “There’s no gap in between where the Secretary and the Chief are on this thing,” the official said. “It’s just a matter of different phases.”

But at the very least, the difference in emphasis was striking. Certainly Milley sounded more ambitious and long-term — even a little like the notorious FCS program — while Esper was more modest and short-term.

Army troops dismount their M2 Bradleys in a simulated assault.

A Family Of Vehicles?

In the hearing, Milley called for an NGCV “family of vehicles” that would “eventually” replace everything from main battle tanks to armored ambulances. But when I pressed Esper on this after the hearing, he only reiterated his past statements that the near-term priority was to replace the Bradley.

Gen. Mark Milley

“The Bradley, the Abrams, and the Stryker (wheeled infantry carrier) were designed and came online many years ago,” Milley told the committee. “Now they’ve had various upgrades and improvements over the years, but they are predominantly technology and ideas that come out of the sixties and seventies….The Abrams, Bradley, and the Strykers, realistically, their lifespan is probably 10, maybe 15 years.”

“So the Next Generation Combat Vehicle…will eventually replace the entire family of vehicles that we have,” Milley said. “There’ll be multiple variants. There’ll be a tank-like variant, there’ll be an infantry carrier-type variant, there’ll be logistics and medical variants. It’s a family of vehicles, it’s not a single vehicle, but they’ll be based off of a common chassis and common engines and powerpacks.”

“It must be optimized for urban operations, which our current families of armored vehicles are not,” Milley added. “It must be optimized so that it can be both manned and either autonomous or semi-autonomous, robotic, depending on what the commander chooses to do in the situation in the battlefield. Those are significant, radical changes.” (Note that the optionally manned NGCV is separate from but complementary with the proposed Robotic Combat Vehicle, which will never have a human aboard).

Esper, by contrast, was much less expansive. He didn’t discuss NGCV at all in the hearing and responded only briefly when I asked afterwards. “The focus is on Bradley right now because that is the vehicle that is reaching the end of its life soonest,” he told me and other reporters. “The focus right now is on… Bradley replacement.”

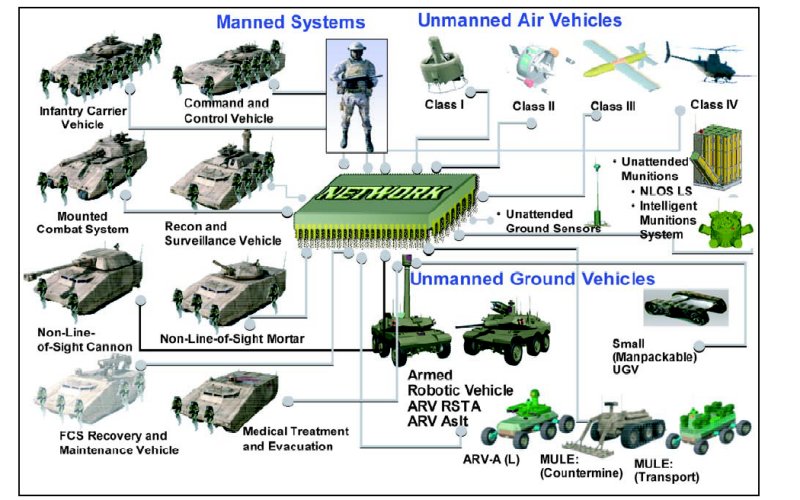

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

What To Build

What does the Army need to replace most urgently? The M1 Abrams and M2 Bradley entered service at almost the same time circa 1980 and both have been extensively upgraded since. But the Bradley’s running out of horsepower and electrical power to handle further add-ons, with at least some crews in Iraq carefully switching some systems off before turning others on so as not to overload the alternator. The Bradley is also less well-armed and armored than the Abrams — it’s basically a transport, not a tank — and can only carry four to six infantry (depending on their equipment), not a full squad. So replacing the Bradley has been the Army’s priority for some time, for example in the cancelled Ground Combat Vehicle program.

Russia’s new T-14 tank (left) and T-15 troop carrier (right) are built on a common Armata chassis.

Could a future family of vehicles start with a Bradley replacement in the near term, which Esper says is the priority, and then modify the basic design to produce a tank, a mobile howitzer, an armored ambulance, and so on, as Milley envisions?

It isn’t an engineering impossibility. Russia’s new T-14 main battle tank and T-15 infantry fighting vehicle are built on the same Armata chassis, with further variants planned, while Israel’s Namer IFV is built on the chassis of the Merkava MBT.

But the last time the US tried to build such a common family of vehicles was the Future Combat Systems, cancelled in 2009. NGCV wouldn’t have to repeat the self-inflicted injuries of FCS, which initially limited its designs to under 20 tons to make them easier to airlift, forcing painful compromises, and coupled them to a complex wireless network and multiple robots in a megaprogram that became impossible to manage. But FCS has become such a byword for disaster that anything resembling it gets Congress and the D.C. cognoscenti nervous.

Even if you could build a battle tank and a troop carrier off the same basic chassis, would it be a good idea? The two missions are historically very different.

A tank is built around the biggest gun available, firing the largest shell as fast and far as possible to destroy the toughest targets, with enough armor to take a hit from comparable weapons. (At least on the front, where traditional tank armor is thickest; an urban warfare vehicle would need to defeat attacks from all sides, above, and below).

An infantry fighting vehicle, by contrast, is meant to carry foot troops into the thick of battle and provide supporting fire: The lion’s share of its internal volume goes to passengers, not weapons. Historically IFVs are also usually cheaper and more lightly armored, but there are rare heavy IFV designs like the Israeli Namer and cancelled US Army GCV that are as heavy and well protected as any tank.

Building an MBT and an IFV off the same chassis implies the same engine and suspension, which implies the same maximum weight, which implies the same amount of armor. So if you want a normal tank and use th same chassis for an infantry fighting vehicle, you end up with a heavy IFV. If you want a normal IFV, your tank ends up pretty light.

Army soldiers fire a Javelin anti-tank missile.

Tanks But No Tanks?

There’s also the recurring argument that you don’t need main battle tanks anymore. Since 1973, many experts have argued they’re obsolete because lighter vehicles, like IFVs, and even infantry can kill them with anti-tank missiles. But Israel and Russia have both developed Active Protection Systems (APS) that can shoot down incoming missiles and RPGs, which are relatively slow and fragile. By contrast, today’s APS cannot stop high-velocity solid shot from tank cannon, which means the big-gun main battle tank may be more important than ever.

Army M1 Abrams tank with a trial installation of the Israeli-made Trophy Active Protection System (APS)

The other problem with heavy tanks, however, is harder to get around: It’s getting them around. Western MBTs like the Abrams, Merkava, and German Leopard weigh 60 to 70 tons — even the Russia Armata exceeds 50 tons — which makes them too heavy for almost any aircraft, many bridges, and some roads. More important in the long run, moving all that weight burns a lot of fuel and wears out parts, requiring a huge supply chain to keep the tanks moving.

But supply lines will be prime targets for precision weapons in future war. The Army’s Multi-Domain Battle concept calls for units to spread out and keep moving to avoid attack, operating “semi-independently” without regular resupply. If main battle tanks are to function in this kind of fight, they’ll have to be very different designs from today’s Abrams, which burns three gallons of gas every mile.

“Someone needs to raise the specter of the MBT becoming obsolete or a liability in the future, if only to make the Army take it seriously and really think it through,” one former Hill staffer told me. “I’m skeptical of the operational viability in a sustained fight. I don’t think anyone has really looked at the logistics of it.”

Top defense insights from 2024

A curated look at standout opinions and analysis covering topics like uncrewed systems, NATO partnerships, US-Saudi defense dynamics, and evolving warfare strategies, spotlighting key issues shaping the global defense landscape.