China and Russia are outmaneuvering the US, using aggressive actions that fall short of war, a group of generals and admirals have concluded. To counter them, the US needs new ways to use its military without shooting, concludes a newly released report on the Quantico conclave. The US military will need new legal authorities and new concepts of operation for all domains — land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

From Little Green Men in Crimea to fortified artificial islands in the South China Sea, from online meddling with US elections to global information operations and to industrial-scale cyber espionage, America’s adversaries have found ways to achieve their objectives and undermine the West without triggering a US military response, operating in what’s come to be called “the grey zone.” No less a figure than Defense Secretary Jim Mattis took on the topic in his National Defense Strategy and in this morning’s graduation address to the Naval Academy.

Gen. Joseph Dunford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis testify before Congress.

“Putin seeks to shatter NATO. He aims to diminish the appeal of the Western democratic model and attempts to undermine America’s moral authority,” ran Mattis’s prepared text. “His actions are designed not to challenge our arms (emphasis added), but to undercut and compromise our belief in our ideals.”

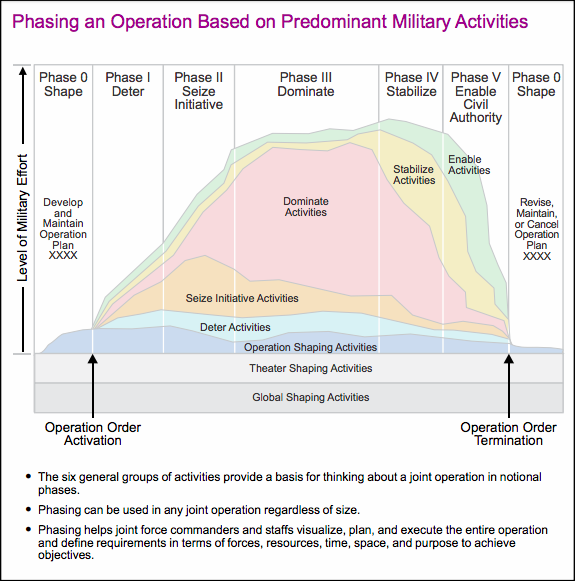

Likewise, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Joseph Dunford, has publicly warned that our adversaries don’t abide by our doctrine, with its clear distinction between war and peace and its tidy phases of escalation. The American military operates in phases, with Phase 0 being peace (officially, “shaping” the environment) and so on. Traditionally, actions other than war are just that to the US and do not merit a military response, let alone a kinetic one. What adversaries are doing is “competition with a military dimension short of a Phase 3 or traditional conflict,” he said as far back as 2016. “(Their) employment of cyber, unconventional capability, space capabilities (and) information operations (go beyond) what we would call Phase 0 shaping.”

“From SecDef and chairman, down to the units in the field… there’s great recognition” of the grey zone problem, said Nate Freier, a researcher at the Army War College. (Freier wasn’t involved with the Quantico conference or writing the report, but I consulted him as a leading expert on the concept). Awareness has grown dramatically since just two years ago, Freier said, when he and his colleagues published a study on the grey zone called Outplayed and Dunford was making his comments on competition.

“I do think that the US military recognizes that dilemma, but I’m not sure they know how to respond to it yet,” Freier told me. “This idea that states like China and Russia are engaged in a persistent campaign to undermine US and allied interests over time, employing methods that fall well short of conventional military conflict…at the national level, we’re still coming to grips with that.”

War & Peace & None Of The Above

“The force is not adequately competing in the ‘gray zone’ below the threshold of armed conflict,” the generals and admirals concluded at the Quantico conference in May, according to the Army Training and Doctrine (TRADOC) report released yesterday. “Peer adversaries/competitors don’t want competitive activities to progress to war because they know the capability of U.S. forces in open conflict. Why would they go there when they are achieving strategic objectives by remaining in competition short of armed conflict?”

I covered the Quantico conference, but, like most attendees, I wasn’t allowed in the special seminar reserved for generals and admirals. The event focused on the effort to coordinate forces across the land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace in a single seamless campaign known as Multi-Domain Operations.

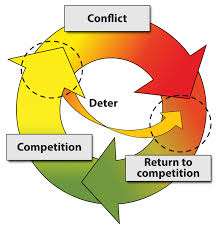

But the senior officers concluded that “battle” was too narrow a term, “too focused on the tactical-level of war during conflict alone,” in the words of the report. The concept should be renamed Multi-Domain Operations to better capture “throughout the competition continuum…. from deterring adversaries during competition, quickly defeating adversaries in a short and decisive action to return to competition, or defeating adversaries in the event of a protracted conflict.”

(“Short and decisive” won’t apply in conflict against a great power, one briefer emphasized during the conference.)

The cycle described here — competition either deters or escalates to conflict, conflict resolves and deescalates to competition — derives from Mattis’s National Defense Strategy, which emphasizes “the reemergence of long-term strategic competition.” Arguably, the word “competition” better captures what’s happening between the US and China, or the US and Russia, than the terms like “peace” or “strategic shaping” (aka “Phase 0”).

The cycle described here — competition either deters or escalates to conflict, conflict resolves and deescalates to competition — derives from Mattis’s National Defense Strategy, which emphasizes “the reemergence of long-term strategic competition.” Arguably, the word “competition” better captures what’s happening between the US and China, or the US and Russia, than the terms like “peace” or “strategic shaping” (aka “Phase 0”).

To the extent that saying “competition” helps people understand Russia and China are “rivals” engaged in “”deliberate malign activities,” Freier told me, the term is helpful. But, it’s not helpful, he went on, if “conflict” and “competition” just become a new pair of rigid categories to replace “war” and “peace,” obscuring the messiness of the real world.

The report from Quantico keeps falling into this intellectual trap. Consider this passage: “Just as the binary war/peace paradigm is insufficient to describe the global operating environment, authorities that are only available during conflict are insufficient. The Joint Force needs certain authorities prior to conflict in order to set the conditions to dominate if hostilities commence.” Yes, the first words of this passage acknowledge that war and peace are not a clear-cut either/or — but the rest of it talks about “during conflict” and “prior to conflict” as if these are clearly distinct phases.

“We’re stuck,” Freier told me. “We are still institutionally and culturally stuck in this five-phase model of operations. Our adversaries certainly aren’t.”

Freier’s Strategy

“The US military should recognize that we can’t operate in this peace-war dichotomy effectively anymore,” Freier said. “We are actually in a persistent competition….That competition sometimes becomes more heated, it sometimes becomes closer to cooperation.” Rather than distinct phases, he said, “it’s a sine wave.”

As tensions go up and down, you always have two goals in mind. “You’re trying to impose costs on the opponent and, at the same time, offer off-ramps to the opponent for de -scalation,” Freier said. “That’s actually a pretty sophisticated approach.”

Every ship that sails, every advisor that goes abroad to train allies, every unit that participates in exercises, needs to be part of a larger plan to demonstrate US resolve and capability, Freier said. The ultimate goal isn’t just to respond to what the Chinese and Russians are doing in the grey zone, he told me. It’s to force them to respond to what we’re doing in the grey.

For example, the US Navy already conducts Freedom Of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) to defy unwarranted maritime claims around the world. But we do them with an even-handedness that’s almost comically scrupulous, challenging everything from China’s island-building in the South China Sea to Malta’s “excessive straight baselines” in the Mediterranean. Instead, Freier says, “freedom of navigation operations should occur in a way that demonstrates military capability.” It’s not just a case of sailing some place to prove you can, he argues: It’s demonstrating you could conduct a military operation there if you needed to.

On land, Freier said, special operations forces originated during World War II as a way to assist or create resistance movements in Axis-occupied territory. During the Cold War, NATO special ops laid the groundwork for partisan activity in West Germany in case of a Soviet invasion. If we rebuilt these “unconventional warfare” capabilities, we could make aggressors think twice about invading territory primed for resistance. We could even demonstrate to Russia and China we could assist resistance movements inside their territory, a threat both countries would take seriously given their long struggles with ethnic separatists.

Actually conducting unconventional warfare on Russian or Chinese territory would escalate right out of the grey zone and into an act of war, Freier notes; he’s just saying we should prove to them we could. Likewise, he doesn’t think the US should conduct Russian-style assassinations on foreign soil or engage in “fake news” propaganda. “There are some places we’re probably not willing to go,” he told me, and that’s a good thing.

Within those moral limits, however, there’s still a lot of innovative things we can think of, especially in cyberspace, Freier said, as long as we let ourselves. “We have to spend some intellectual capital right now in defining what ‘presence, ‘maneuver,’ and ‘action’ look like in those spaces, short of open military conflict,” he told me. “The United States has to become less rigid in its view of military operations.”

After inauguration, who is running Trump’s Pentagon?

With Pete Hegseth, Trump’s pick for defense secretary, still working through the Senate confirmation process, there is no clarity on who is leading the US military.