Frontline 3D printers. Ammunition delivery drones. Dune buggies, both diesel and all-electric. Sophisticated logistics networks. In its ongoing Sea Dragon exercises and simulations, the US Marine Corps is looking at a lot of new technology to keep far-flung troops supplied in the lightning maneuvers it envisions for future great-power war. But the most important change is happening in the minds of young Marines.

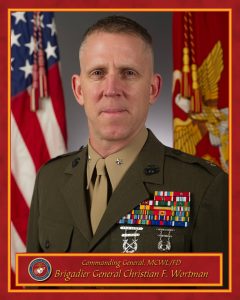

“This is a challenging thing. A lot of it is about mindset,” said Brig. Gen. Christian Wortman, commander of the celebrated Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL). “And once we arm the Marines with the information they need to be successful in that environment, they’re generally excelling…. More than anybody else, they’ve got a lot of skin in that game, and they’re very serious about doing it well.”

But what is it that they need to do well? Historically, Marines are in effect a ground force with one big advantage: They can maneuver at sea to surprise, outflank, and overwhelm the enemy. But since 9/11, they’ve mostly operated out of lavishly supplied ground bases in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now the Marines aren’t just returning to their sea-based traditions: They’re doubling down on them with new concepts of operation that look like World War II Pacific “island hopping” on fast-forward.

“We’re going to have to operate small, fast, and lethal,” Wortman told reporters this afternoon. “We’re going to need to be able to transition seamlessly from land-based locations back to the sea base, and from those sea-based locations to different locations ashore.”

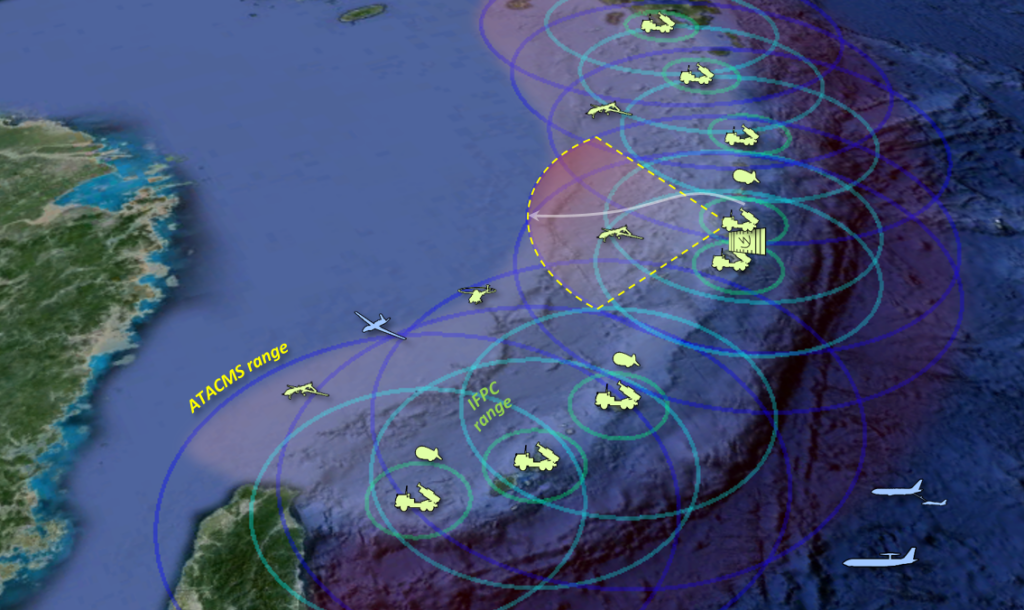

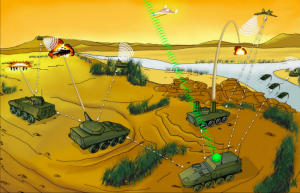

Land-based missiles deployed at “Expeditionary Advance Bases” could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

Multi-Domain Marines

In other words, the Marines won’t just move from ship to shore and on inland, but rather from ship to shore back to the ship and then on to a different shore. The idea is to alternate rapidly between (1) coming from the sea to seize bases ashore and (2) using bases ashore to affect the fight at sea. This is a particularly Marine Corps manifestation of a wider concept, one all the services are exploring, known as multi-domain operations — so called because the idea is to hit the enemy from all domains of war at once: land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

In a future Pacific war with China, for example, Marines might

A Marine Corps amtrak (formally an Amphibious Assault Vehicle or AAV) exits the well deck of the USS Harpers Ferry

- come ashore on a strategically located island — by aircraft, landing craft, and Amphibious Combat Vehicle —

- to destroy an enemy ground installation threatening the US fleet, like a long-range radar, missile battery, or airbase, or

- to set up an Expeditionary Advanced Base (EAB) to launch their own air raids with F-35Bs or fire anti-ship missiles at the enemy fleet; and then

- rapidly re-embark aboard Navy amphibious ships to go do it all over again somewhere else.

Sea Dragon Phase I, last year, looked at how infantry battalions — the heart of the Marine Corps — could survive and win in this environment. Phase III, in 2019, will look at resilient networks that can function despite jamming, hacking, and attacks on US satellites. But none of this will work without supplies: food, spare parts, ammunition, batteries, and above all fuel. Logistics is the focus of this year’s ongoing Phase II.

The traditional arsenal of democracy approach is to build a central iron mountain of supplies and then distribute them by frequent convoys of ships, planes, and trucks. That was hard enough in Iraq and Afghanistan, where roadside bombs and simple distance complicated logistics. In a future war against a great power foe like Russia or China, this hub-and-spoke approach is simply too slow and, worse, too vulnerable to attack by long-range precision missiles.

Four Fronts

So in Sea Dragon, the Marines are looking for solutions on four fronts:

1. Ways to move supplies more quickly and in smaller packets, retail logistics instead of wholesale.

On the ground, that might be giving foot troops small numbers of, basically, dune buggies — all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) like the Polaris MRZR-D — to carry about 1,500 pounds of cargo. Such light ATVs can move at a faster pace than men on foot, but in places where big trucks can’t go. Unlike the Army, the Marines don’t seem too interested in self-driving heavy trucks, probably because they expect to be moving mostly over water or rough terrain. Unlike an Army HEMTT, the MRZR is small enough to fit inside a V-22 tiltrotor.

In the air, the Marines are looking at a variety of unmanned air vehicles (UAVs) with cargo capacities ranging from 50 to 1,000 pounds to deliver tailored supply packages straight to frontline units. They started experimenting with this concept using the K-MAX unmanned helicopter in Afghanistan in 2011, but they’ve yet to field something at scale. At one point, the Marines were interested in adding a cargo mission to the MUX armed scout drone, but that weighed MUX down too much. Now, Wortman says, the Warfighting Lab is “getting close” to making concrete recommendations for a variety of cargo drones to Commandant Robert Neller.

2. Ways to reduce the amount of supplies that need to be moved.

Fuel is the biggest drain on supply lines, for example, so the Marines are experimenting with both hybrid-electric and all-electric vehicles like the Nikola Reckless.

Spare parts are generally lighter and easy to transport than fuel, but the problem is having the exact right part in the right place at the right time, so the Marines are enthusiastically exploring 3D-printing on demand to make the part on the spot when needed. So far, Wortman’s staff said, this kind of frontline additive manufacturing is limited to plastic or, more recently, nylon parts that don’t require extensive safety testing, but the technology continues to advance.

3. Ways to know exactly what supplies to move where, when.

Units uncertain when they’ll next be resupplied tend to stockpile extra of everything, but the weight adds up and slows them down. On the other hand, the military can’t just adopt commercial just-in-time logistics: A missed critical shipment might shut down a factory for a day, but it could get troops killed.

So the Marines are trying to build a logistical command-and-control network that can give supply officers detailed, up-to-the-minute data on what units are running out of before they actually run out. The really hard part, though, is this system needs to stay up and running in the face of high-tech enemies who can hack its network, jam its transmissions, or just trace the location of the signals and drop a missile on it.

Marine Corps notional depiction of various Armed Reconnaissance Vehicle (ARV) variants and drones working together

4. New ways of fighting that require fewer supplies.

That may mean accepting a higher risk of, say, running out of fuel or ammunition. This is a potential culture shock to US military willing to spend millions of dollars of ordnance and fuel to save a single life.

It’s one thing to ask young Marines to go without the hot showers and fast food that were commonplace at big Forward Operating Bases in Iraq: They’re a tough lot, they can take it and even revel in it. It’s another to ask Marine leaders to accept the price of victory may be more of their young Marines getting killed. Against well-armed enemies, however, it’s sadly unrealistic to expect the (by historical standards) low casualties of the last 17 years.

Innovation Warfare

Even the technological solutions will require new ways of thinking, and some “non-materiel solutions” may not require new technology at all. New tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) are a big part of the Sea Dragon experiments. “We’re providing our lessons learned and our observations (to the rest of the Marine Corps), so we’re learning as an entire organization,” Wortman said.

It’s not just taking notes on how well the technology works. “A large amount of the information that we gather is going to be the innovative solutions (from) the Marine,” said Wortman’s project officer for “hybrid logistics,” Maj. Steve Shull. “There may be a concept of employment for a particular technology, but when you give it to the young Marine, he’s going to be innovative… He, often, or she can demonstrate a use of the technology that had not been previously envisioned.”

The concepts the Warfighting Lab comes up with aren’t holy writ, but rather a baseline for young Marines to build on, “a point from which to deviate,” said Maj. J.B. Persons, a special projects officer at MCWL. “Give Marines new tools or toys, and they’ll surprise you every time.”

Sure, inventing this new way of warfare will be hard, but it builds on traditional Marine Corps virtues such as initiative, adaptability, and sheer cussed toughness.

“The folks at the edge are champing at the bit to figure that out, and it plays to our strengths,” said Maj. Justin Gogel, a project officer at the lab. “Marines want to be relevant and they want to survive and they want to be lethal….They’ll figure out a way.“