AUSA: The Army is giving its electronic warfare force more troops, more training, and a more prominent role in combat headquarters, senior officers said here Thursday, pushing back on criticisms that the service neglects EW even as Russia and China pull ahead.

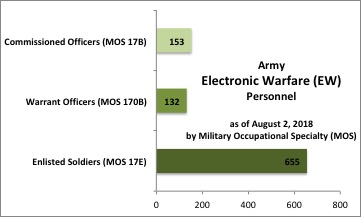

- The number of EW troops has increased from 813 (both officers and enlisted) in 2015 to 940 today and it’s growing. While just a fraction of the formidable Russian EW force, that’s still a 15 percent increase in three years, remarkable at a time when the Army as a whole shrunk by 4 percent. What’s more, it reverses a stark decline in previous years when the Army decided to get rid of EW specialists because it no longer needed to jam radio-controlled roadside bombs in Iraq.

- EW training is being expanded. All new Army electronic warfare officers (EWO) will start with the same 14-month course as cyber operations officers, but the EWOs will then get an additional three months of training specifically in electronic warfare. Enlisted EW specialist training will probably quadruple in length from nine weeks to 36, equal in length to the new enlisted cyber operator course.

- EW officers will lead new combined cyber/EW cells on Army headquarters staffs at every echelon from brigade to division, corps, and regional Army Service Component Command. Many units had some form of Cyber/Electromagnetic Activity staff before, but these CEMA cells are now being enlarged, standardized, and put without exception under leaders drawn from the EW force.

Now, even when complete, these reforms won’t fix all the Army’s problems, much of which comes down to hardware. The service is racing to field the kind of robust communications network that can get orders and intelligence through in the face of high-end jamming. It’s still years away from fielding the kind of high-powered, long-range offensive radio jammers that the Russians put to lethal effect in Ukraine, although it has been testing shorter-ranged systems in Europe. And there’s no clear timeline to develop a drone-mounted offensive jammer that would free the Army from its current reliance on a small number of manned aircraft from other services, particularly Navy EA-18G Growlers and Air Force EC-130H Compass Calls.

Also unnerving to some electronic warriors is how their specialty is being merged into the larger and better-funded cyber branch. But that merger, Army leaders say, is about elevating electronic warfare, not subsuming it.

The goal, they say, is integrating electronic warfare with cyber warfare, information operations, and other high-tech functions in a new kind of electromagnetic combined arms as essential to 21st century warfare as Panzers, Stukas, and the radio were to the German blitzkrieg. While cyber warriors can hack landline networks on their own, they need signals intelligence (SIGINT) and electronic warfare to help them find and penetrate wireless networks. (Fast-moving tactical units rely on wifi for command, control, and communications because they can’t be tied to fiber optic cables). And if cyber forces can’t hack the enemy by messing with their data, the digital 1s and 0s, it’s up to electronic warfare to spoof enemy sensors and jam their communications by physically transmitting radio-frequency signals. Cyber, EW, and signals are far stronger together than apart.

“It’s Not Just Cyber”: Uniting The Tribes

“They’re no longer tribal rivals, we’re mission partners,” Lt. Gen. Stephen Fogarty told a cyber and networks conference at the Association of the US Army on Thursday. Electronic warfare and cyber warfare, signals (communications) and signals intelligence, psychological operations and information operations, he said, “everyone came to the same conclusion that we had to work together, and that if you stood alone, frankly, you were just going to become irrelevant.”

Other leaders at the conference made similar points, but Fogarty’s particularly important because he’s both the former head of the Army Cyber Center of Excellence at Fort Gordon, Ga. and the new chief of Army Cyber Command (ARCYBER). But while “cyber” was the hot buzzword to slap on everything a few years ago, those names don’t reflect the full scope of what those organizations do, including electronic warfare, and they need to change.

“We’ve got to be careful about boxing ourselves in by the term cyber,” Fogarty told the conference. “It’s not just about cyber. It’s not just about cyber.”

“In three years or four years or five years from now, we’ll no longer be called Army Cyber Command,” he went on. “We’re going to something else that actually reflects the totality of the capabilities,” perhaps some variation on “Army Information Warfare.”

As a first step to that change, Fogarty is meeting all this week at his Fort Belvoir, Va. headquarters with leaders from multiple specialties — not only cyber but electronic warfare, information operations, and the signal corps — to refine Cyber Command’s mission statement and priorities.

There’s another aspect to this conceptual challenge: developing an offensive mindset. The Army’s efforts so far have focused, understandably, on defending its networks from hacking and jamming. Now the service wants to take the offensive in both cyberspace and over the airwaves of the radio-frequency spectrum. In fact, Fogarty argued, as our potential adversaries catch up to us technologically, the silver lining is they’re making themselves more vulnerable to high-tech means of attack.

“You’re going to hack and jam us?” the Russians might well retort. “You and what army?”

The answer is the new cyber/electronic warfare force the US Army is building up. And that corps is very different than the centralized strategic force the military has created for pure cyber warfare, in which defensive and, even more so, offensive teams are closely controlled by high-level strategic like Fort Meade, home of the NSA. By contrast, the Army is creating a decentralized structure for combined cyber/electronic warfare at the tactical level — and at every echelon from brigade to theater, electronic warfare officers will be in the lead.

Electronic Warriors In The Lead

What does it take to fight and win the invisible war of electrons? A lot more than the Army initially thought.

Back in 2016, after years focusing on strategic cyber forces, the Army started exploring what it then called Cyber Support to Corps and Below (CSCB), which was later renamed Cyber/Electromagnetic Activity (CEMA) Support to include electronic warfare and other functions. The initial plan was to deploy a team of four cyber specialists to a brigade conducting war games at Combat Training Centers. It quickly became clear a much larger contingent was required to set up the necessary infrastructure for training, let alone conduct effective operations.

Even with more people in place, however, there was no common database to plan these operations. That’s particularly problematic in highly technical operations that require extensive coordination. Cyber attacks need electronic warfare to transmit their malware into the enemy network; electronic warriors need signals intelligence (SIGINT) to help them hone in on the enemy transmissions; SIGINT and the signals corps needs EW to avoid jamming certain frequencies because we need to use them to spy on the enemy or for our own communications.

Officers from the different specialties end up kludging together the technical details at the last minute. That’s not good enough, said Fogarty: “We can do better than Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint in the TOC (Tactical Operations Center) 30 minutes before an operation.”

The technical piece of the solution is the Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool, being developed by Raytheon. EWPMT began life purely as an aid to EW planners but took on spectrum management and signals intelligence functions as well. An early version, Ravenclaw, has been deployed to Europe.

The human piece is new and larger CEMA cells at multiple echelons, with more personnel at lower levels closer to the fight:

- Brigade-level cells will double in size from five personnel to 10, gaining a second EW officer, three additional enlisted EW specialists, and, for the first time, a cyber operations officer.

- Division cells will grow from five to nine, adding EW enlisted and a cyber officer.

- Corps cells will grow from six to eight.

- Army Service Component Commands (ASCCs), part of regional combatant commands (COCOMs), have no standard structure today but will have a CEMA cell of seven under the new plan.

A crucial detail: At every echelon, the leader of the CEMA cell will be an electronic warfare officer, taking advantage of EWO’s additional training in how to combine cyber and EW.

Now, these headquarters personnel are primarily planners and coordinators, not frontline cyber/electromagnetic combatants. Army officials said the actual hackers and jammers will come mostly from

- new Electronic Warfare Platoons to be created in each brigade’s Military Intelligence Company (MICO);

- new Electronic Warfare Companies in each Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade; and

- 45-person Expeditionary CEMA Teams, two of which currently exist. Both ECTs are trained and administered by the Army’s central Cyber Warfare Support Battalion (CWSB), but they’re attached as needed to combat brigades to conduct operations. The Army has said elsewhere the ECTs may become division and/or corps assets (presumably, once there are enough of them to go around).

In addition, said ARCYBER’s Brig. Gen. William Hartman, brigade commanders will be able to reach back over Army networks to experts in the US. They’ll also have legal authorities to take action in cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, he said, including authorities previously reserved to “Army Cyber [Command] or a Joint Force Headquarters.”

But humans need special equipment, like computers and jammers, to actually do anything in the cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, just as they need planes to fly in the air or ships to sail the sea. (Coordinating all these forces is the aim of the emerging doctrine known as Multi-Domain Operations). The Army is making progress on EW gear, but it’s still a long road.

Gearing Up, Eventually

Right now, the Army doesn’t have a lot of cyber or electronic warfare gear for frontline units. “The equipment we brought to JRTC (the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, La.) was really built to fight the last war,’ said Brig. Gen. Hartman. “It was large, it wasn’t mobile, it was built to sit on a FOB (Forward Operating Base). It wasn’t built to maneuver with a brigade combat team.”

That required some field modifications and quick some commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) additions. The range of cyber/EW sensors, for instance, went from 900 meters to five kilometers.

In such systems, agility and adaptability are more important than raw power, several senior officers said, because the threat keeps changing, driven by Moore’s Law and Russo-Chinese ingenuity. To meet that challenge, said Raytheon’s information operations director, Frank Pietryka, EW technology has evolved away from traditional brute-force hardware with a few hardwired functions: point at the enemy, dial in the frequencies they’re using, and blast out radio waves to jam them. Today’s software-driven systems, he said, can collect signals intelligence (SIGINT), detecting and analyzing enemy signals, and then transmit sophisticated jamming signals to interfere with those signals in subtle ways.

“We shouldn’t have a bespoke solution for everything,” said Lt. Gen. Fogarty. For example, in 17 years of fighting terrorists and insurgents, the main mission of electronic warfare has been jamming radio-controlled roadside bombs (RCIEDS). But against a high-tech, heavily armed adversary, he said, the urgent need might be to jam the fuses on anti-tank missiles and artillery shells, or to attack the enemy’s command networks and GPS-equivalents. (While he didn’t name them, he’s presumably thinking of Russia’s GLONASS and China’s Beidou).

The Army is currently testing a range of relatively lightweight, low-power, and short-range gear in Europe, much of it small to be carried by a single soldier. In the future, however, it plans on a more powerful truck-mounted system called TLIS — Terrestrial Layer Intelligence System, which combines SIGINT and EW — and some kind of airborne jammer, probably on a drone. (Jammers send out powerful energy pulses that make them easy targets, especially flying jammers that can’t hide in the terrain, so an expendable platform is preferable to a manned one). Fogarty also believes the Army should invest heavily in decoys, pulsing out false signals to draw the enemy’s precision weapons away from our troops.

Wielding these new tools effectively will require new technical learning and tactical creativity from Army commanders. Today, all too often, infantry, tank, artillery, and aviation (helicopter) officers see networks as something their communications staff should handle in the back room, out of sight, jabbering to each other in geeky “dolphin speak” while the real men actually fight with actual weapons. But now the Army is trying to use the network itself as a weapon. That means commanders need to understand it, not as well as technical specialists do, but at least well enough to employ it effectively.

“The network is a weapons platform,” said Brig. Gen. Joseph McGee, former deputy commander of ARCYBER and now director of the Army’s Talent Management Task Force. “Most maneuver leaders understand the weapons platforms that they’re employing: They understand the limits and constraints of an Apache helicopter or an Abrams tank. I’m not sure we’ve dedicated enough time and effort to help the maneuver leaders understand the network. “