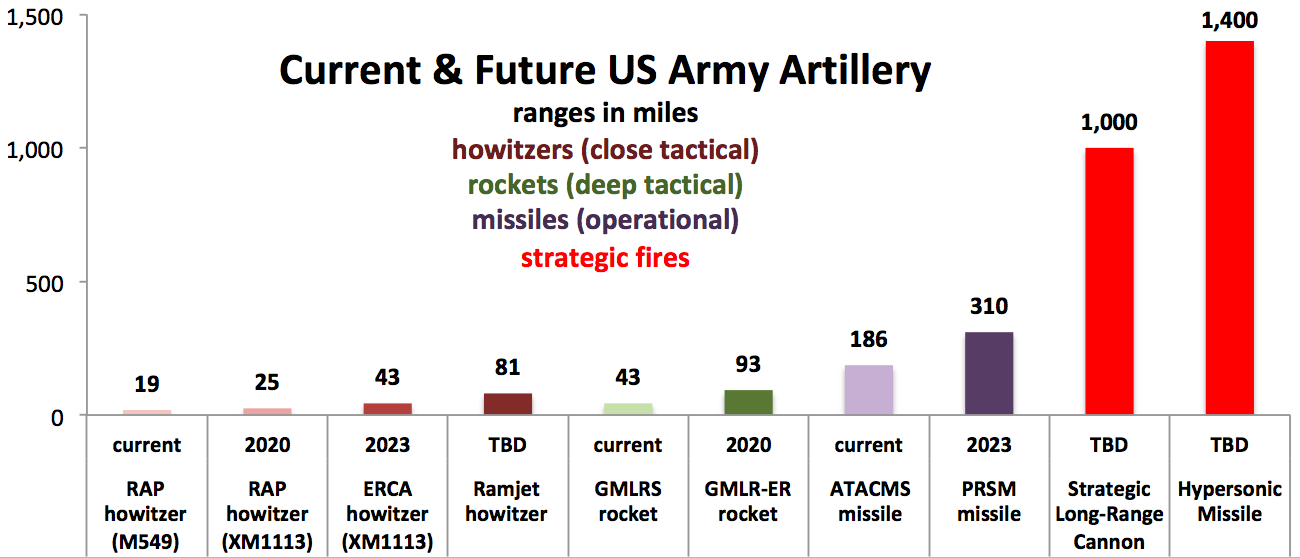

SOURCE: US Army. SLRC and Hypersonic Missile ranges as reported in Army Times.

AUSA: Why is the Army confident it can build a Strategic Long-Range Cannon to shoot with precision more than one thousand miles? Because the superweapon will be essentially supersizing proven technologies found in the existing 155 mm howitzer and rocket-boosted artillery shells from the 1980s.

“I don’t want to oversimplify, (but) it’s a bigger one of those,” Col. John Rafferty told reporters here. “We’re scaling up things that we’re already doing.”

Soon to be a one-star general, Rafferty is the Army’s modernization director for Long-Range Strategic Fires, the service’s top priority, which covers everything from revolutionary hypersonic missiles to longer cannon barrels for the venerable 155mm. While the Strategic Long-Range Cannon — SLRC, pronounced (unfortunately) “Slorc” — will hit targets at ranges comparable to the bleeding-edge hypersonics, Rafferty emphasized the cannon is built on proven principles, just bigger.

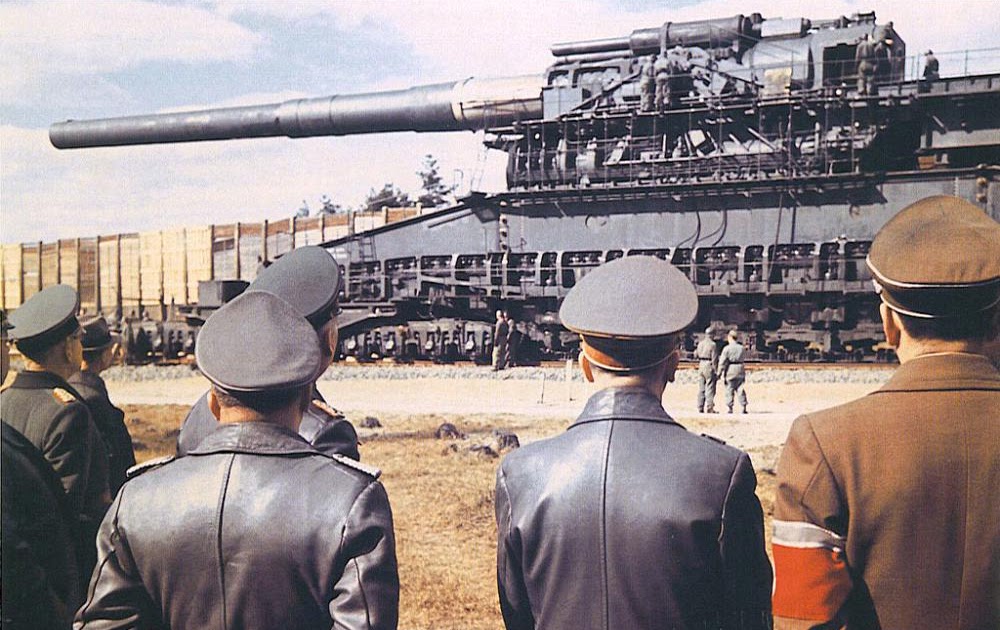

How much bigger are we talking about? Will it just look like a scaled-up M109 Paladin howitzer, I asked, or more like a World War II railroad cannon, or even Saddam Hussein’s infamous never-finished “supergun“?

It’ll be “pretty big,” one of Rafferty’s officers said, but it’ll be “mobile” — or, he added after a pause, at least “movable.”

“Relocatable,” another officer suggested.

The Reason Why

If this is so doable, why has the Army never done it before? “It’s never been done before (because) before, we haven’t been pushed,” Rafferty said. “We haven’t had a role in strategic fires.”

Today the Army relies on the other services’ planes and missiles for long-range strike, with airpower available almost on-demand for ground troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. But as the Pentagon turns from fighting guerrillas to deterring great powers, war planners are increasingly anxious that advanced Russian and Chinese anti-aircraft systems may make the skies a killing zone with nowhere to hide, forcing the US to rely on ground weapons that can be hidden from the enemy in tunnels, forests, and other terrain.

The problem is today’s artillery just isn’t up to it. Badly neglected for the last 15 years of guerrilla warfare, to the point a famous essay by disgruntled officers called it a “dead branch walking,” US field artillery is “outranged and outgunned” by its Russian and Chinese counterparts, as former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster told Congress in 2016. So in 2017, at last year’s AUSA conference, the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, officially made Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) the service’s No. 1 modernization priority.

The full LRPF portfolio involves not just the strategic cannon but a whole arsenal of weapons with overlapping but successively longer ranges. Rafferty’s team is leading some efforts while supporting others, but he was able to provide new details on almost all of them at AUSA.

Tactical Fires

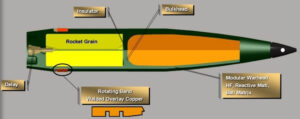

For tactical cannon, there’s the Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) program, which is building a new XM1113 Rocket Assisted Projectile (RAP) and a longer barrel for the standard 155mm howitzer. (Since the exploding gunpowder only pushes the projectile while both are confined within the gun tube, a longer barrel means a longer push, higher muzzle velocity, and hence longer range).

ERCA’s goal is to double the range from 30 km with the current RAP to 70 km. The Army might ultimately almost double the range again, to 130 km, by using more aerodynamic warhead designs or novel propulsion technologies as ramjets. (In US units, that’s going from 19 miles to 44 to over 80).

Rafferty said he’s convinced the next-gen propulsion technology is feasible, but his team is intensively studying whether it’s cost-effective for the additional targets it could reach.

The 70-km version has already been test-fired more than 50 times at White Sands, New Mexico and would enter service around 2023. Whether to pursue the 130-km model, let alone when, is still to be decided.

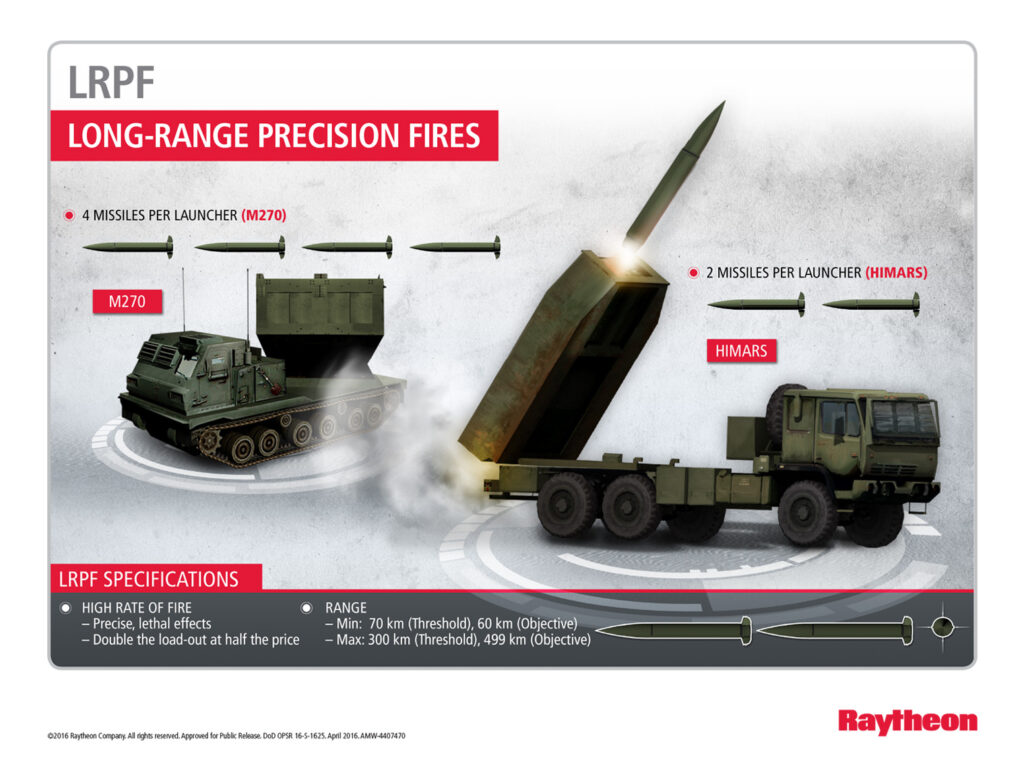

For tactical missiles, the Army is upgrading its Guided Multiple-Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) to an extended range version, GMLRS-ER. That more than doubles the range from 70 km to 150 (from 43 miles to 93). Both versions can be fired from either the tracked M270 or the HIMARS truck.

This is a pre-existing program already well underway and set to enter service in 2020, with the LRPF team in support. Rafferty didn’t offer any new details on it at AUSA.

Operational Fires

For what it calls “operational” ranges, the service is replacing the existing Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) with a new Precision Strike Missile (PRSM), increasing range roughly 70 percent, from 300 km to 499 (186 miles to 310).

What limits PRSM’s range is not technology but the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which bans ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500-5,500 km. If the INF treaty collapsed — increasingly likely given Russian violations and US threats to develop countermeasures — Rafferty said it would be “entirely possible” to extend the range further.

But that’s just one of many potential upgrade options or “spirals” the LRPF team is studying. Others include improved navigation for warzones where GPS is jammed, loitering munitions that can circle the target area until they spot the enemy, and a seeker warhead to hit moving targets — even ships at sea.

Lockheed Martin and Raytheon got contracts to build prototypes in 2017, their designs are done and they should start test flights next year. The Army plans to pick a winner in 2021, the LRPF team said. Originally set to enter service in 2027, PRSM is now being accelerated so the first few missiles — what the Army calls an “urgent materiel release” — will be available to combat units in January 2023. The PRSM program manger is focused on getting the baseline missile out on time, while Rafferty focuses on getting the upgrades lined up to add as soon as possible afterward.

These new missiles won’t need new launchers, however. Like the ATACMS and the MLRS, PRSM will be fired from the M270 tracked vehicle and HIMARS truck, just from a different container. While a HIMARS can carry one ATACMS and an M270 can carry two, the PRSM will be smaller, despite its greater range, doubling shots to two and four respectively.

Strategic Fires

All the above systems replace or improve something the Army already has. The strategic fires systems would be something new for the US Army (but not for China): ground-based weapons with ranges normally associated with aircraft.

Unlike the PRSM missile, these weapons would seem to violate the INF treaty even in their basic form, without any upgrades, but Rafferty and his team say they have the legal okay to proceed. “We’re going to play by the rules,” he said, “until we’re told the rules have changed.”

The Army won’t discuss technical details. Our best-informed speculation is that, by using cutting-edge propulsion technologies that weren’t envisioned by the authors of the treaty, the Army’s weapons might technically be neither ballistic missiles nor cruise missiles. But that kind of hair-splitting probably won’t convince the Russians, who already argue that America’s long-range drones violate the treaty, even as they build banned weapons (with nuclear capability) themselves.

The Strategic Long-Range Cannon (SLRC) would probably be the shorter-ranged of the two, according to at least one reliable report, at about 1,000 miles. It would use a cannon barrel to launch artillery shells with built-in rocket boosters that ignite in mid-air. Since the cannon is reusable, this should be significantly cheaper than using one-shot rockets for every phase of flight. Lower price for shot, in turn, allows the Army to take out large numbers of lightly protected targets: truck-borne missile launchers, radar antennas, and mobile command posts, for example.

SLRC is a uniquely Army project, with Rafferty’s team orchestrating a technology demonstration at a date not yet announced.

By contrast, the future hypersonic missile would be run by the multi-service program office now being created, Rafferty said. The Army LRPF team’s role, he said, is to get soldiers trained and organized to use the weapon as soon as it’s ready.

While probably too expensive to use on large numbers of soft targets — hence the need for the strategic cannon — the hypersonic weapon’s extreme velocity would allow it to penetrate the toughest defenses and smash the hardest targets, such as buried bunkers. It reportedly would have a longer range than the cannon as well, out to 1,400 miles. Specifically, it would be a hypersonic boost-glide weapon, accelerating to enormous speed in the first phase of flight and then coasting — if you can call Mach 5-plus “coasting” — and skipping in and out of the atmosphere like a stone thrown across a lake.

All the services are working together on a Common Hypersonic Glide Body, but they’re customizing it and adding the right booster rocket for their specific launch platform: artillery, aircraft, or ships and submarines. The Navy has the lead because fitting the weapon into a Vertical Launch System (VLS) tube and firing it from underwater is the biggest technical challenge, Rafferty said. By contrast, a land-based launcher is relatively simple. Potentially, Rafferty said, “we can get there the fastest.”

How does the Army find targets at such long ranges, though? It hasn’t had its own long-range reconnaissance aircraft since the Air Force became independent in 1947. It doesn’t run the nation’s high-powered spy satellites. But the intelligence community “is really meeting us halfway,” Rafferty said.

While it won’t be simple to connect Army artillery to the interagency intelligence networks, the data is there. “The more I know,” Rafferty said, “the less I worry about our ability to find the targets.”