WASHINGTON: By choosing a lower-risk engine option to upgrade thousands of helicopters, General Electric’s T901 turbine, the Army is taking a new approach to its long-mismanaged modernization. As Army Secretary Mark Esper has described it, the service is seeking a low-risk revolution, inching towards ambitious goals by evolutionary means. It’s a strategy that will likely carry over to other programs like the Next Generation Combat Vehicle, where senior officers have already said they want mature technology, but with room for future upgrades.

The hard truth is that, having wasted tens of billions and almost 30 years since the end of the Cold War, the Army is out of time. It must modernize urgently against a resurgent Russia and a rising China.

But after decades of incremental improvements to 1970s designs, its existing weapons — from the M2 Bradley armored vehicle that the NGCV will replace, to the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter that GE’s new engine will upgrade – are overweight, underpowered, and running out of room to grow. Meanwhile, the Army’s attempts at a high-tech great leap forward — the Comanche stealth helicopter, the Crusader super-cannon, and above all the sprawling Future Combat Systems — kept getting cancelled because they were unaffordable, unfeasible or both.

So when Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley called for “10X” (tenfold) improvements in technology, it sent shivers up the spines of observers like myself who still bear the scars from FCS. But Milley, Esper and their subordinates insist the Army’s learned its lessons, streamlined its bureaucracy, and can steer a safe course between the Scylla of blue-sky overreach on one side and the Charybdis of diminishing-returns incrementalism on the other.

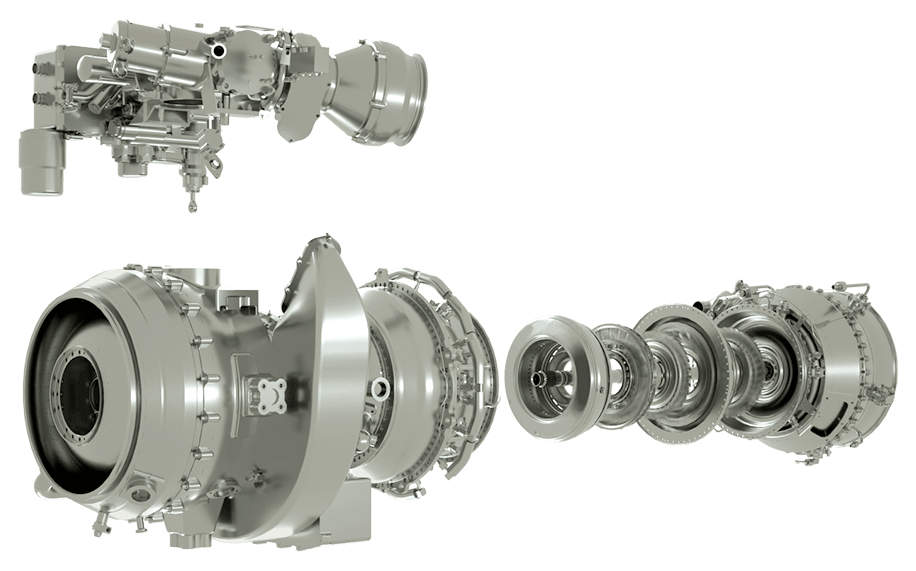

So far this has been mostly well-intentioned talk, declarations of what the Army intends to do on still-nascent programs like NGCV. But Friday’s announcement that the service had chosen incumbent General Electric and its GE T901, a single-spool turbine, over the rival ATEC T900, a more sophisticated dual-spool design, suggests this philosophy is actually driving big-dollar decisions. ITEP isn’t in mass-production yet — the award was a $517 million, five-year Engineering & Manufacturing Development (EMD) contract — but the Army is now committed to the GE engine.

“GE was certainly the low-risk choice,” aviation analyst Richard Aboulafia told me. “It’s not just the T901 design: It’s also their multi-decade experience with the T700” – the engine T901 will replace, which has been used on Army helicopters since 1973 – “and their large, global product support capabilities.”

The ITEP Example

Even before last week’s decision, the Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP) split the difference between evolution and revolution, by design. With its helicopters weighed down by years of upgrades and struggling at high altitudes in Afghanistan, the Army launched what would become ITEP in December 2006. Ever since, it’s consistently asked for a new engine with 50 percent more horsepower, 25 percent less fuel consumption, and a 20 percent longer service life – all pretty revolutionary – that could fit into existing UH-60 Black Hawks and AH-64 Apaches – evolutionary.

After 12 years of R&D, both competitors should be able to hit these targets. “I’m sure that both company’s proposals fully met all of the requirements,” said Mike Hirschberg, executive director of the Vertical Flight Society and a longtime advocate of the new engine.

So what’s the difference? First, it’s the competing companies’ track records.

ATEC, the Advanced Turbine Engine Company, is a joint venture of Honeywell and Pratt & Whitney, both well-established engine manufacturers. Pratt & Whitney, however, mainly make jets for airplanes, so they’re relatively unknown to the Army. Honeywell builds the massive, 4,800-horsepower T55 turboshaft that powers the Army’s hundreds of CH-47 and MH-47 Chinook heavy-duty helicopters. But GE’s 2,000-hp T700 is on every single AH-64 Apache in the Army and on every H-60 variant in the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Coast Guard – thousands of aircraft.

“GE not only marketed a simpler engine design, but is also a much more familiar customer, which further reduces risk,” said CSIS scholar Gabriel Coll. “To the degree that ATEC had an established relationship with Army, it seems to be primarily through Honeywell [on] Chinook, which was less relevant to the ITEP competition” – being a much larger engine – “and does not deliver nearly the same quantity to the military as GE.”

The second risk factor is the design of the engine itself. The old, familiar T700 is what’s called a single-spool engine: one compressor and one turbine, both spinning on the same shaft. GE stuck with the proven, familiar single-spool approach for its T901.

But the Pratt-Honeywell ATEC T900 was a dual-spool design: two compressors, two turbines, two shafts. That obviously adds complexity and weight, both particularly undesirable in an aircraft. But it allows each compressor-turbine combo to spin separately, each at its optimal speed. As the aircraft maneuvers, changing what it needs from its engines, sophisticated software shifts the burden from one spool to the other for maximum efficiency and minimum wear. Having two sets of components working together also doubles the opportunity for future upgrades. Pratt and Honeywell claimed their dual-spool T900 would have 4 percent better fuel efficiency (which adds up), last 10 percent longer, and have 10 percent more margin for future growth than a single-spool equivalent.

Of course GE disagrees, saying they explored a dual-spool design and rejected it as too heavy and hard to maintain, especially in rugged frontline conditions. As for potential future growth, GE can point to its track record on the T700, which went from 1,500 horsepower in 1973 to over 2,750 on the latest Special Operations version today – an 80 percent improvement in the same basic single-spool design.

“You can make an argument either way about spools,” Aboulafia shrugged. Rolls-Royce actually offers three-shaft turbofans, he noted. It really depends on the mission and what the customer wants.

And what the customer wanted, it seems, was a known quantity – both in the manufacturer and in the design.

Beyond The Black Hawk

Installing new, more powerful engines will keep the Army’s thousands of Black Hawks in the air and out of the scrapyard for decades to come. But ultimately, the service wants to move to radically new machines capable of much higher speeds and longer ranges. Those are the Future Vertical Lift (FVL) prototypes from Bell and Sikorsky, which, like the ITEP engine, represent over a decade of work finally coming to fruition just as the Army really needs it.

The service has said it wants ITEP to power the FVL aircraft as well, and one competitor, Sikorsky, says its prototype scout helicopter, the S-97 Raider, can accept either ITEP engine. But will this really work on larger variants of FVL?

“The FVL thing sounds somewhat nonsensical,” Aboulafia harrumphed: ITEP might work on a light scout like Raider, maybe, but not a larger transport aircraft to replace the UH-60, let alone the CH-47. Bell’s FVL prototype, the V-280 Valor, is setting speed records with a pair of massive engines with a combined 10,000 horsepower You’d need to bolt four ITEPs together to match that. (Bell executives have in fact proposed killing off ITEP to get faster funding for FVL).

Might ATEC’s more ambitious design have done better at this than GE’s single-spool engine? “Dual-spool would be the way to go if you really wanted to push the boundaries with FVL engine performance,” Coll told me. “But it seems like, at least for the initial stages of FVL, a completely new airframe design is a bigger priority than a completely new engine….My sense is that they’re seeking incremental change from ITEP, in part, to allow for more transformational change with FVL.”

FVL itself, however, has taken the long road to revolution. It actually began way back in 2009, just three years after what became ITEP. Both programs have a chance to reconcile the opposites the Army wants – big improvements in technology, but mature enough to build today – because they’ve had over a decade to get ready.

General Dynamics Griffin II armored fighting vehicle, a light tank being proposed for the Army’s Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) program.

Can that model apply to other Army programs? The service’s light tank program, called Mobile Protected Firepower, has come down to a competition between BAE’s update of a cancelled design from 1997 and General Dynamics’ evolution of an European vehicle introduced in 2002. GD is offering another version of the same 2002 design for the Bradley replacement, the Next Generation Combat Vehicle, while BAE is offering the even older CV90 and Rheinmetall is gambling on its all-new Lynx – but Army officials have emphasized that, while they want the latest electronics and new weapons, they want them on a proven chassis. Meanwhile it’s upgrading its existing tanks with Trophy anti-missile defenses and buying Iron Dome anti-rocket systems, both systems developed years ago by Israel and proven in combat.

Other Army efforts, like new thousand-mile missiles, don’t have such mature development programs to build on. That means the Army may have to give up on the perfect solution, for now, and urgently go after the good-enough.

“Early signs suggest that the Army is actually implementing the ‘80 percent solution approach’ for the Big Six,” said Coll’s CSIS colleague Rhys McCormick, citing the off-the-shelf Israeli systems, “but I’d hesitate to definitively call it a success at this point.” It’s just too early.

“On something like Next Generation Combat Vehicle, there’s been some disconnect between how Secretary Esper talks [and] some in the operational community,” McCormick went on. “This isn’t to say that this disconnect can’t be resolved, but the expectations vs. reality on the NGCV requirements is something we’re watching.” The next big test, he said: the eagerly awaited, already overdue 2020 budget.

Israel signs $583 million deal to sell Barak air defense to Slovakia

The agreement marks the latest air defense export by Israel to Europe, despite its ongoing war in Gaza.