PENTAGON: The Army will move about $10 billion more from lower-priority programs to its flagship Big Six over the five years 2021-2025. That’s on top of the $33 billion already reallocated in the Future Year Defense Plan for 2020-2024. In particular, the new FYDP will include major increases for lasers and other directed energy weapons, the service’s No. 2 civilian said here this morning.

As a result, by 2025, if you add up all the new technologies the Army is pursuing — from hypersonic missiles to drone-killing lasers, from robotic tanks to high-speed aircraft, from secure networks to AI-assisted rifles — the service’s investments in developing new weapons to counter Russia and China will finally equal its investments in upgrading old ones built for the Cold War, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

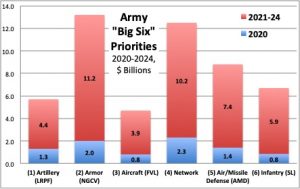

Big Dollars For The Big Six

“By the end of this FYDP, the ’24-25 timeframe, you’ll see about 50 percent of Army investment into developmental systems and 50 percent legacy,” undersecretary Ryan McCarthy told reporters in his E-ring office. “When we started this journey in the fall of ’17, it was 80-20: 80 [percent] legacy, 20 percent development.”

October 2017 was when then-Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley — now nominated for chairman of the Joint Chiefs — announced the Army’s biggest reorganization in 40 years to pursue six modernization priorities for major war: artillery, armor, aircraft, networks, air & missile defense, and soldier gear (in that order). That December, in an exclusive interview with Breaking Defense, McCarthy told me the Army’s budget plan for 2019-2023 would reallocate over $1 billion in science & technology funds from lower priorities to support the Big Six. A year later, McCarthy announced the service would move $31 billion into the Big Six over the 2020-2024 plan — a figure that rose to $33 billion when the actual budget request came out this March.

Click graphic to expand. LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. SOURCE: US Army. (Click to expand)

For the 2021-2025 plan the Army is now finalizing, McCarthy said this morning, “we put out a target of 10 billion dollars over the FYDP… and we are in very good shape there.

“I’m very encouraged by what I’ve seen,” McCarthy said. “We’re about to slap the table on the POM [Program Objective Memorandum] here, by no later than the middle of June; I think we’re.. .going to finish maybe a day or two early — because you have the whole system energized and it’s changed behaviors.”

Now, the service is still finalizing its figures for the next few weeks. After that, in June, the Army’s plan goes to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, which makes its changes and submits the revised plan to the White House Office of Management, which makes further changes and submits the final budget to Congress, which is free to — and often does — disregard the whole thing.

So McCarthy was understandably unready to give hard-and-fast figures at this early stage. But he did sound very confident the service would at least meet the $10 billion target.

Lasers, Hypersonics, & Sequestration

One area of investment McCarthy highlighted: directed energy. The service has been working on laser weapons for some years now, with a plan to test a 50-kilowatt drone-killing laser on an 8×8 Stryker armored vehicle in 2021 and field batteries of laser Strykers in ’23. A parallel program is putting a 100 kW laser on a heavy truck. But in recent months, the Army’s newly appointed Program Executive Officer for high-tech programs, Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood, has reviewed the directed energy portfolio, seeking to cull lackluster laser projects and focus funding on programs most relevant to the Big Six, especially air and missile defense.

“Gen. Thurgood did 45-day review of directed energy,” McCarthy said. “In the ’21 [plan], you’ll see the investments start to increase.”

Thurgood has also reviewed hypersonic weapons, another high-tech high-priority, and one where the Army is working closely with the Navy and Air Force. In fact, the common “glide vehicle” to carry conventional warheads at Mach 5-plus is derived from an Army joint project with Sandia National Laboratory, and the service is finding some surprising synergies with the other services.

“The fundamentals of firing off a truck [are] not that much different than firing off a sub,” McCarthy said. “Where the fundamentals change dramatically is off of some attack aviation platform.” But the basic package that goes on an Army Transporter-Erector-Launcher vehicle and a Navy Virginia-class submarine are remarkably similar, he said, which means the two services can share a lot of test data, shortening the test program and getting the weapon into combat units faster.

All of this, of course, assumes that Congress and the White House can agree on a budget. Key committees have already rejected the administration’s attempt to do an end-run around Budget Control Act caps. That means President Trump, Senate Republicans, and House Democrats must make a deal to raise the caps — hopefully before the fiscal year begins October 1st — or else sequestration will automatically cut about $150 billion from the Pentagon budget.

The specter of sequestration would be “my greatest concern” if budget negotiations break down this year, McCarthy said. The Army could “probably figure it out” if the fiscal year begins with a stopgap Continuing Resolution to continue spending at 2019 levels while Congress and the White House thrash out 2020, he said, but the closer we get to the 2020 elections, the harder it becomes to make a deal.

A Continuing Resolution “would stall our modernization agenda,” McCarthy said. “The Budget Control Act [caps] would not only collapse modernization, it would collapse readiness. It would be a massive hit for the Department of Defense.”

Army halted weapon development and pushed tech to soldiers faster: 2024 in review

The Army spent 2024 pushing its new “transformation in contact” initiative while also pivoting away from several key weapon development initiatives.