SB>1 Defiant in flight over the Sikorsky’s Jupiter, Fla. test site last week.

JUPITER, FLA.: Army Captain Tammy Duckworth lost both her legs 16 years ago when her UH-60A Black Hawk helicopter was hit by crude rocket-propelled grenade over Iraq. Last week, Senator Duckworth watched a test flight of a potential Black Hawk replacement meant to survive cutting-edge Russian anti-aircraft systems.

Sen. Tammy Duckworth, a former Army helicopter pilot who lost both legs in Iraq.

“When I was flying into Abu Ghraib [in 2004], I was slow, I was exposing my belly to everyone that wanted to shoot at me,” Duckworth said. “I got shot down flying 10 feet above the trees, going a hundred knots.”

The new Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) must fly at least 230 knots — 150 mph – at low altitude and be able to zigzag around obstacles to evade enemy radar. While the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant hasn’t reached that speed yet in its test program (rival Bell’s V-280 Valor already has), it did show off its low-altitude agility here, pirouetting and flying backwards for the assembled dignitaries.

“I was very impressed by the maneuverability,” Duckworth told reporters afterward. “As a former Alpha-model Black Hawk pilot, I’ve got to say I was salivating.”

The two contenders for the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA): The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant compound helicopter (top) and the Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor (bottom)

Just as crucial, Sen. Duckworth – a prominent member of the Senate Armed Services Committee – said she was heartened by how the Army was handling its high-tech, high-priority, high-cost Future Vertical Lift effort. FVL includes both FLRAA and a light scout, the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA).

“Both programs are ahead of schedule,” Duckworth said. “I’m very pleased…This is rare for defense procurement. [And] I’m really encouraged by the open communication that Army leadership and industry seem to be having.

“We can’t be pulling back on funding,” she said. “We’re actually asking for [additional] money to take advantage of the fact that we’re ahead in development.”

But, I asked, how can the Army convince Congress and the taxpayers that FVL won’t be a repeat of past aviation acquisition disasters, like the stillborn Armed Aerial Scout and the RAH-66 Comanche, cancelled only after the service invested $7 billion?

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy

“I was in flight school in 1993, and they showed me a mockup of the Comanche and [said], ‘it’s going to fly next year,’” Duckworth recalled. Instead, it was cancelled just months before she was wounded. Why? Her take: “The Comanche was [driven] by what a bunch of aviators wanted, not necessarily by looking forward to what the real mission was on the ground.”

“The Comanche helicopter, it was extraordinary what they created; it just cost too much,” said Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy. “The Army made a decision — it was right when I entered the Pentagon over a decade ago — [that] they couldn’t afford it.

“What’s different about this time, we’re organized very differently against the problem,” McCarthy said. Instead of the longstanding bureaucratic divide between combat veterans writing wish-lists of high-tech requirements and acquisition officials trying to actually build something on a budget, the 18-month-old Army Futures Command and its FVL Cross-Functional Team “have brought the requirements organization together with acquisition,” he said. “There’s much greater clarity.”

Pointing down the table, McCarthy went on: “Gen. Rugen and Mr. Mason here, the requirements leader and the acquisition executive responsible for this program, they’re attached at the hip. They’re going to work very hard to prevent requirements fluctuation from confusing the manufacturers.”

“The Army has learned its lesson,” Sen. Duckworth said.

Has it?

Maj. Gen. (ret.) Rudy Ostovich

Lessons Learned?

Some 16 years after Comanche died, does the Army really have a clearer grasp of what the mission requires, what industry can deliver, and what the budget can afford? Yes, it does, said a retired two-star general who helped write Comanche’s initial requirements and then saw them bloat.

“I believe Army Aviation leadership has learned its lessons from Comanche regarding FVL,” said Maj. Gen. (ret.) Rudy Ostovich in an interview. “We are now properly organized around the problem.”

“FARA and FLRAA are no more ambitious than Comanche,” Ostovich told me. “In fact, in many ways, Comanche was far more ambitious [relative to the technology at the time]. I flew a number of the prototypes and experimental mission equipment packages that were on board – it was pushing the state of the art.”

The cancelled RAH-66 Comanche

“With the Comanche, we said we needed a scout helicopter that was tougher than a woodpecker’s lips, but could be electronically connected to the rest of the fighting force, so it could be the ‘digital quarterback’ — and it had to be low-observable on radar,” he went on. “But low observability on radar is almost irrelevant to a scout helicopter or even a platform that does long-range assault, far less important than is acoustic stealth.”

(In other words, helicopters fly so low they rarely get seen by radar; the enemy knows a helicopter is coming when they hear it.)

Worse, as over-reaching as the initial requirements were, the Army didn’t stick to them. Instead, it kept adding to the wish-list over time, which increased Comanche’s capabilities – at least on paper – but also its size and price. “What began as a $7.5 million, 7,500-pound aircraft in 1990, when I signed that requirements document, grew to almost twice that weight and certainly twice that cost by 2004,” Ostovich told me, “because it was no longer an armed reconnaissance helicopter: It became focused on light attack, and somehow killing tanks was more important than finding the enemy.”

“We have to guard against that with regard to FARA,” he added. The Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, after all, already has the tension between the two missions embedded in its very name.

Sen. Duckworth, for her part, sounded a similar warning for the FLRAA transport. “We need to not let the requirements start to meander and creep around, because otherwise we’ll never get to where we need to go get these things fielded,” she said in Florida. “Let’s laser-focus on what Army aviation needs to do for that Army ground commander to execute his mission, and then everything else will fall in behind.”

The context for this comment: The Marines and Special Operations Command have both expressed interest in FLRAA, but they proposed speed and range specs well in excess of what the Army requires.

“If the other services want to follow behind and develop something afterwards and tweak it for what they need, that’s fine,” the senator said, “but we cannot build a Franken-aircraft… that’s going to meet the Marines’ need and the Air Force’s need and the Army’s need. I’m sorry, but they’re different missions.”

High Performance Without High Cost?

So what does FLRAA need to do for the Army? “Great-power competition is moving towards the Asia-Pacific region,” said Sen. Duckworth, who was born in Thailand. “We’re now talking about going from island to island, from distances that are far greater than any model Black Hawk could do.”

Approximate ranges in miles between the Russian enclave in Kaliningrad and select NATO capitals. SOURCE: Google Maps

Greater range and speed are also relevant in Europe, the Army believes. Like China, Russia has vast batteries of precision missiles that can devastate airfields and forwarding refueling points too close to the front line. That forces Army aviation to use bases further back – and to penetrate deeper into enemy airspace to destroy those missile launchers.

Since the performance the Army seeks for both the FLRAA transport and the FARA scout is aerodynamically impossible for conventional helicopters, every design in contention for either program is distinctly unconventional. There are tiltrotors (the Bell V-280 transport), compound helicopters with pusher propellers (the SB>1 Defiant transport and Sikorsky Raider-X scout), even something that looks like Comanche but with small wings (the Bell 360 Invictus scout), and more.

How can the Army be confident these novel designs will work? For one thing, the V-280 and SB>1 are all actually flying, as is the aircraft from which the Raider-X derives, the S-97. McCarthy himself has personally seen all three in the air, and Army experts are working side by side with each contractor to gather data. The Office of the Secretary of Defense has conducted its own independent assessment of the technologies as well, to highlight potential risks.

Sikorsky S-97 Raider on its first flight

In March, drawing on all this information, the Army will pick two competitors to build full-up prototypes of FARA and two competitors to do “competitive demo and risk reduction” of key technologies for FLRAA. (There won’t be additional FLRAA prototype aircraft beyond the V-280 and SB>1 already flying). While this “downselect to two” is a bit of a formality for FLRAA – Bell and the Sikorsky-Boeing team are the only candidates with aircraft actually doing test flights – it’s a real fight for FARA, where there are five rival designs.

The Army hasn’t said when it will select a final winner to mass-produce either aircraft, but it wants to get FARA in service ca. 2028 and FLAA by 2030.

Ostovich feels fairly confident about both. “FLRAA-related technologies are sufficiently mature, and the acquisition strategy is achievable,” he told me. “Though FARA brings a bit more risk because of its more aggressive schedule, I believe it can make it the finish line on time – [although] a budget cut in FY20 did not help.”

“The pacing item,” he warned, “is the budget.” And that’s ultimately up to Congress.

“I am personally committed to maintaining strict oversight [of FVL] and also for advocating to improve it,” Sen. Duckworth said. “I’ve got a personal bent towards this, but not to the extent I’m going to blow the taxpayers’ money.”

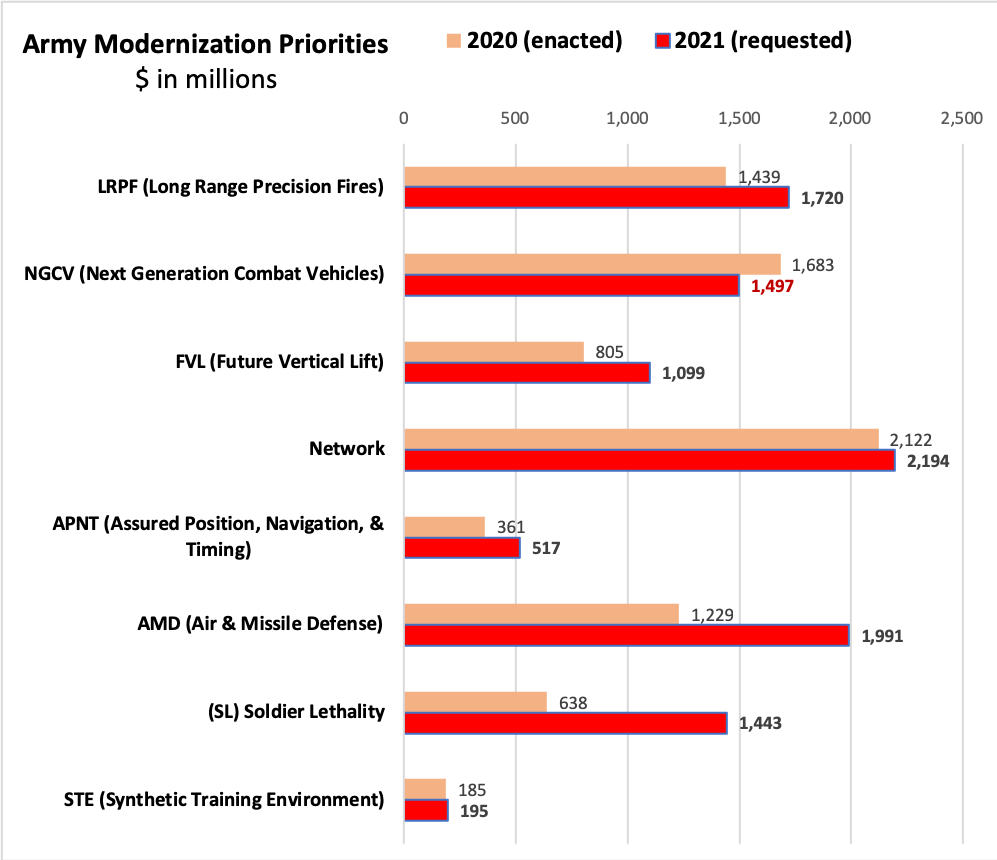

2020 and 2021 funding for the Army’s modernization priorities, listed in order of importance. Breaking Defense graphic from aArmy data.

That means the aircraft need to be economical to build and, even more important in the long run, to maintain, repair, and fuel. For FLRAA, the senator said, “below $10,000 per hour of flight time is really the goal.” As for up-front procurement costs, she went on, “we can’t be spending upwards of $60 million per airframe, [or] we can’t field the number of airframes that we need.”

“This will be about an affordability decision,” agreed McCarthy. “There’s just so many dollars to go around and we’re modernizing the entire formation: missile defense, armored vehicles, long-range precision fires.”

To free up funding for FVL and other modernization priorities, “we’ve made very difficult choices divesting legacy programs — and there’s going to be more of that,” the secretary went on. “Leadership is going to make tougher and tougher decisions.” As new systems move from research to design to prototype to mass production, costs will rise and budgets will get tighter.

“We don’t have a choice,” McCarthy said. “We’re running out of letters to upgrade the existing platforms” – for example, Capt. Duckworth flew a UH-60A; the newest model is the UH-60V.

“They’re 40-year-old systems,” he said. “The technology will not endure.”