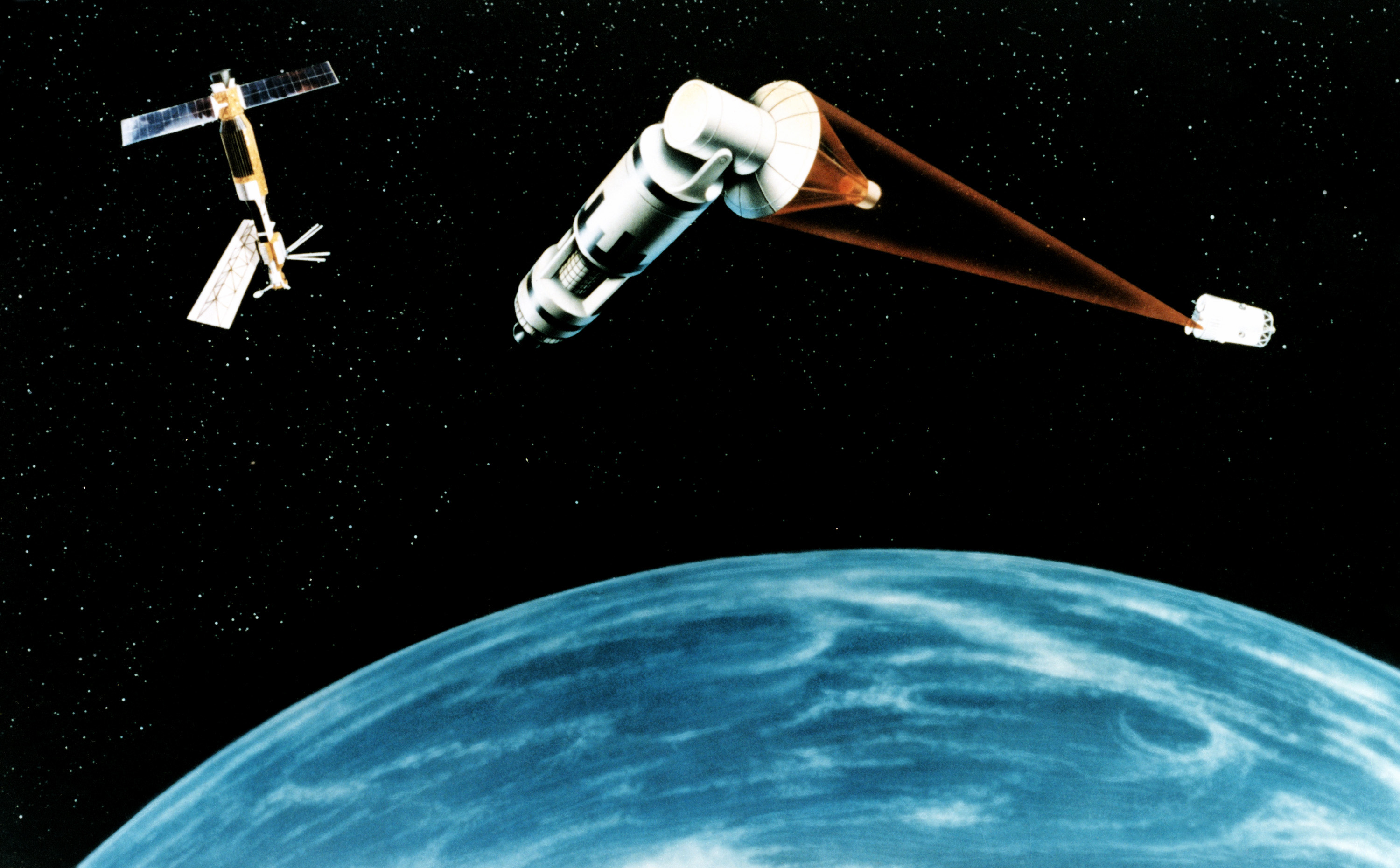

An Air Force graphic showing a hypothetical space-based laser system. (USAF)

Dr. Jessica West is a Senior Researcher at the Canadian peace research institute Project Ploughshares. Her research and policy work is interested in technology, security, and governance with a particular focus on peace and security in outer space. In this new op-ed, she discusses the issues surrounding an expected anti-satellite weapon test — first revealed by Breaking Defense last week — and how it could impact the idea of norms in space.

In July, the Defense Department released an unclassified memo on its space operations, identifying five “Tenets of Responsible Behavior.” Significantly, these principles move beyond finger pointing to standard setting. Reinforced are some core tenets of the Outer Space Treaty, including due regard and the avoidance of harmful interference, as well as the long-standing expectation that states limit the creation of long-lived debris. The memo even fleshes out a few more specific practices in communications and pre-notifications.

But there is one glaring gap in the memo: Nowhere does it describe the testing of weapons as irresponsible or as a practice to be avoided.

Now, as Breaking Defense first reported, the US is planning to demonstrate a new, secret anti-satellite capability against an object in orbit. By so doing it will seek to set the standard for a “responsible” weapons test, in contrast to what have long been denounced as “irresponsible” activities by other states. However, it also risks derailing what little progress has been made to develop international military and security-related norms for outer space.

Norms that focus on “responsible behavior” are pitched as an alternative to traditional arms control agreements. Rather than restricting specific weapons or their use, they aim to make military activities in space safer. If weapons are going to be tested in space, goes the argument, then tests must be conducted in a way that minimizes harm to other operators and the environment. This is the logic behind UNIDIR’s call for testing guidelines.

However, if norms are intended as an alternative to formal arms control, then linking them directly to a weapons test is not only awkward but also potentially self-defeating. Put another way, if norms are used to legitimize weapons testing, the use of norms as either an alternative or a pathway to arms control will be a harder sell for many states.

Already, some states see international inconsistencies in how “responsible behavior” is interpreted. Tying the first practical expression of such behavior to a weapons test can only reinforce such an observation and erode efforts to build “likemindedness,” trust, and community — features on which norms depend. On a pragmatic level, conducting such a test before an anticipated Open Ended Working Group on responsible use at the United Nations this fall seems to display more than a touch of tone deafness.

Finally, there is a risk that applying a veneer of ”responsible behavior” to inherently destabilizing activities will stretch the concept to the breaking point. This has already happened to the idea of “peaceful purposes” in space. For decades, peaceful purposes have been expanded and stretched to include widespread military use, obscuring a simmering arms race.

And if, for a time, the idea of peaceful purpose seemed to keep the worst military impulses in check, the veneer of peace has now been largely abandoned. More and more states are embracing the legitimacy of warfighting in outer space. It’s hard to see how labelling such actions “responsible behavior” will help.

Norms reflect shared values and expectations of appropriate conduct. A common understanding of what “good” behavior means should lead to a strong social and moral obligation to act out such principles. Norms, at their most effective, result in collective self-governance. This is their appeal in security circles, which see a focus on voluntary behaviors as a more flexible, less restrictive, and ultimately more achievable approach to collective security than a negotiated treaty.

The development of workable norms is not easy. It’s hard to find the basic universal values that can bring together different cultures and interests and groups. It’s even harder to put those values into practice.

For example, everyone claims to be committed to a space environment free of contamination, one that is sustainable for future generations. And yet the amount of space debris increases year after year. Instead of making our practices match our principles, we often stretch those principles out of any recognizable shape in an attempt to accommodate bad practices.

The world values norms and wants them to work. As arms control agreements in other domains falter, norms are one of the few tools we have left to keep violence in check. We want and need space actors to engage in behaviors that are truly responsible and peaceful. Only with such norms in place can our world come together to explore and conduct other activities on the Moon, or beyond.

As someone who advocates for the development of new norms for military activities in space, I recognize both the value of effective norms — and the difficulty in creating them. Strong norms are the glue of collective governance. But without the right ingredients, that glue won’t adhere to all surfaces or will soon dry out. Needed are shared principles and values, combined with constant efforts to build community and trust through dialogue.

Weapons tests aren’t listed in the recipe and will only spoil the process. The right norms will restrain, not promote weapons testing in space.