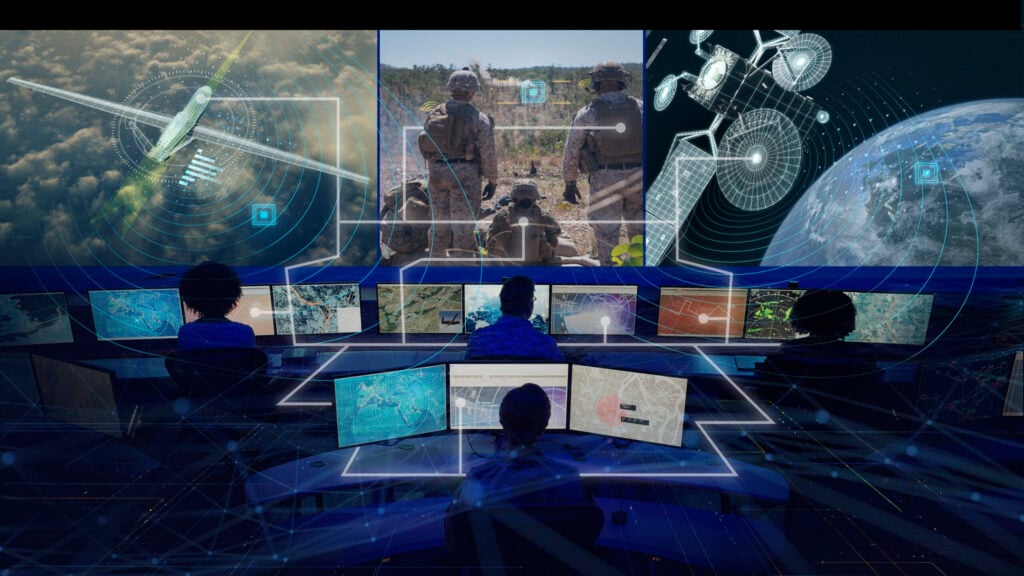

JADC2 illustration by Northrop Grumman.

WASHINGTON: If the Defense Department’s ambitious strategy for building a joint battle network is ever going to come to fruition, a central authority is needed, according to a new study based in large part on an in-depth review of past Pentagon failures.

Such an organization hub for Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) could take a the form of a Joint Executive Program Office, similar to that established to manage the tri-service F-35 jet; a new independent agency under the Office of the Undersecretary for Research and Engineering (OUSDR&E), akin to the Missile Defense Agency; or establish a lead Combatant Command to set requirements, the study says.

The study, authored by Todd Harrison of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and released today, first provides a primer on how a US “battle network” would work to defeat a peer adversary, and how that adversary’s battle network would work to counter the US.

It further explains the advantages of “algorithmic warfare” based on the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, as well as the less-often spelled out disadvantages — which include severing adversary command, control and communications (C3) capabilities to the point that leadership would be unable to recognize efforts to de-escalate a conflict.

The study’s central argument is that the current decentralized approach to JADC2 is not likely to succeed in building a highly integrated, automated network to produce near real-time effects, both offensive and defensive, across all domains of warfare. Currently, the Air Force and Space Force are pursuing JADC2 via its Advanced Battle Management System program; the Navy through Project Overmatch; and the Army through Project Convergence.

CSIS graphic showing advantages of a battle network like that envisioned under DoD’s JADC2 strategy.

If the individual services retain separate and independent budget and schedule authority over JADC2 efforts related to their domains, “a likely outcome” will be “that the services would each develop a new generation of stove-piped command and control systems that are highly capable within their respective domains. Cross-service and cross-domain interoperability would be a secondary priority — or worse, an unfunded requirement,” the study maintains.

Called “Battle Networks and the Future Force Part 2: Operational Challenges and Acquisition Opportunities,” the CSIS report looks to the Pentagon’s past, specifically the efforts in the early 2000s to develop “network-centric warfare,” to warn today’s policy-makers about the pitfalls involved in developing JADC2.

The network-centric concept included the creation of an underlying “Global Information Grid (GIG), which was scoped to include the entire information technology infrastructure of DoD, including government-owned and leased software and hardware across all missions (strategic, operational, tactical, and business).”

DoD reorganized acquisition offices to set standards for developing new C3 software to support GIG. The Joint Staff further issued a “set of Net-Ready Key Performance Parameters (NR-KPPs) to levee requirements across programs at all acquisition category (ACAT) levels.”

And the Army, Navy and Air Force launched a series of flagship weapons acquisition programs to enable network-centric operations, such as “the Army’s Future Combat System (FCS), the Air Force’s Transformational SATCOM (TSAT), the Navy’s DDG-1000 destroyer, and the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS)” all based on the development of next-generation technology.

CSIS graphic of how an adversary’s battle network would work to defeat US all-domain operations.

The similarities of the network-centric warfare push to the evolution of JADC2 are almost eerie. And it failed. Every single one of those efforts just listed were “cancelled or curtailed,” the study shows, with little to show for the billions invested.

Harrison points to for key reasons why:

- Overly ambitious acquisition programs;

- Assigning responsibility without authority;

- Issuing requirements and policies prematurely, before the necessary technology was sufficiently developed;

- Expanding the scope beyond battle networks to include office management networks and the like.

Thus, the study recommends that, besides creating a centralized JADC2 authority, the Pentagon “make key top-level architecture decisions, including narrowing the scope of JADC2 to just battle networks, as soon as possible; and “expand its typical make/buy analysis to include options for buying services instead of products and including systems that may be commercially owned and operated.”