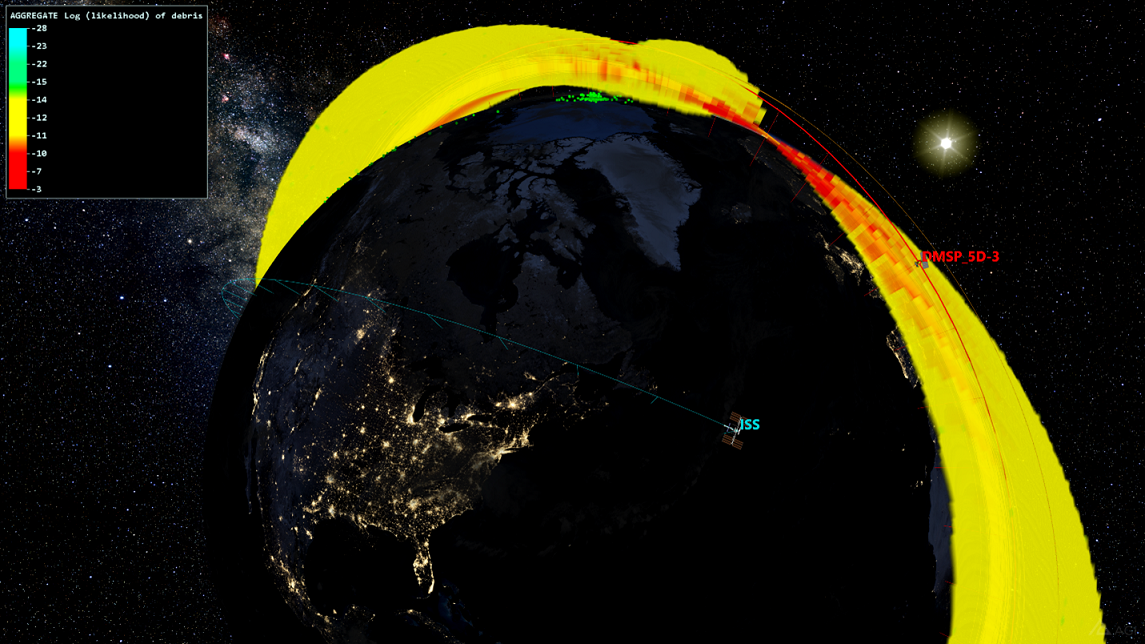

Path of the debris from Russia’s Nov. 15 ASAT missile test over the first 24 hours after impact with the Soviet-era Cosmos 1408 satellite, according to COMSPOC. (COMSPOC/CSSI volumetric analysis, with rendering by AGI, an Ansys Company)

WASHINGTON: Significant amounts of debris from Russia’s Nov. 15 anti-satellite weapon test will continue to threaten US military weather and spy satellites, as well as the International Space Station over the next several years, according to a detailed analysis by commercial space tracking firm COMSPOC.

The satellite most imperiled in the first 24 hours after the A-235/P-19 Nudol ASAT system’s interceptor smashed into Russia’s Cosmos 1408 bird was one of America’s four remaining Defense Meteorological Satellite Program weather sats, DMSP 5D-3 F18 (USA 210). Two other DMSP birds — DMSP 5D-3 F16 (USA 172) and DMSP 5D-15 (USA 147) — were also among the top 50 at-risk satellites in the immediate wake of the ASAT test, according to COMSPOC’s analysis.

As Space Force is already racing to replace the DMSPs before they simply conk out from old age, the military can hardly stand to lose one through a collision.

Fortunately, the risks to the DMSPs will reduce as the Cosmos 1408 fragments disperse over time, Dan Oltrogge, COMSPOC’s Integrated Operations and Research director and a key author in this analysis, explained in an interview. However, some pieces that ended up in a similar orbit as the weather sats (roughly 850 kilometers) will remain there, and thus remain a potential threat.

Overall, the analysis shows that the bulk of roughly 1,500 debris pieces being tracked by Space Command’s 18th Space Control Squadron — 904 pieces of which have been put in the public catalog — will de-orbit within approximately a three year timespan.

At the moment, however, the risks to active satellites in LEO from the ASAT debris remain real.

Hugh Lewis, head of the Astronautics Research Group at the UK’s University of Southampton, on Monday tweeted an analysis of predicted conjunctions, or close approaches, between satellites and the Cosmos 1408 debris for the first week of January. That analysis showed 8,917 likely conjunctions where a sat and a debris fragment would pass within five kilometers of each other — scarily close in terms of collision risk.

ISS Risks Grow Over Time

The COMSPOC analysis also shows that Russian government claims that the debris would not harm the International Space Station are blatantly not true. In fact, the opposite appears to be the case.

At the time of ASAT test, COMSPOC listed the ISS as 20th on the list of most imperiled spacecraft. But the analysis shows that risks of a catastrophic collision with the ISS will continue to grow as the debris pieces spiral downward from the impact point into the Earth’s atmosphere, Oltrogge said.

The debris will be “coming from 460 kilometers [where the intercept happened] and dropping through the ISS altitude,” he said, “and over time, there will be increased risk because of that.”

The ISS, which currently carries US, Russian and one German crew member, operates at an average altitude of some 400 kilometers. And due to its orbital parameters and the laws of physics, it sometimes passes through the “falling” debris not just once but twice during its trek around the Earth.

Another factor contributing to the high ISS risk, Oltrogge added, is that the station is big — much bigger than a satellite — so there is simply more surface area for a potential debris strike.

COMSPOC analysis of threats from the ASAT test debris was based on Space Command’s catalog of space objects made available at the 18th Space Force’s Space-Track.org website, which does not include spy satellites operated by the National Reconnaissance Office. The orbital parameters of those satellites are classified, although most of the agency’s imaging satellites in LEO are routinely tracked by civilian astronomers (not to mention the Russians and the Chinese.)

However, most Earth observation sats — including NRO birds and commercial imagery satellites the agency increasingly relies upon for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance data — orbit at around 440 kilometers. Thus, as the ASAT debris begins to de-orbit, they are in the same boat as the ISS.

China Focuses on Starlink

China’s crewed Tiangong space station, which has a typical orbit slightly lower than the ISS, also will be threatened as the debris de-orbits. However, Beijing has not issued any public condemnation of the Russian test.

Instead, the Chinese government has recently focused its public ire on SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, designed to provide global Internet connectivity from space. Beijing on Dec. 3 issued a note verbal to the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs in Vienna complaining that on two occasions — once in July 2020 and once in October 2021 — Tiangong’s core Tianhe module had to dodge a Starlink to avoid a crash. The complaint also asked the UN to “remind States parties” (i.e. the United States) about their obligations under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty to ensure that their space operators follow the treaty’s provisions.

On Monday, Oltrogge and co-author Sal Alfano posted a blog detailing the Chinese Space Station’s collision risks with other operational satellites, including Starlink, over the past year. The study found that “the two reported Starlink conjunctions represent only a small fraction of the total expected close approaches that Tiangong would have experienced during a one-year period,” just 2.4%.

“Tiangong is down at 390 kilometers altitude, it’s well below Starlink,” Oltrogge told Breaking Defense. He explained that it is likely the close approaches happened when the Starlinks were maneuvering from where they are ejected from their launcher to their operational orbit, which is at about 550 kilometers.

“These findings suggest that Starlink spacecraft do not place undue flight safety burden on the Tiangong Space Station crew or their flight dynamics staff as compared to other active spacecraft that transit Tiangong’s orbit altitude band,” the analysis found.

The authors, however, sounded a serious warning for Tianong, the ISS and other spacecraft in LEO.

The data “highlight the importance of sharing orbit and maneuver information” especially regarding planned maneuvers (which happen for stationkeeping and disposal as well as collision avoidance), noting that Tiangong alone “can be expected to come within 5 km of other active spacecraft every nine days on average.”

Textron, Leonardo bank on M-346 global experience in looming race for Navy trainer

“The strength we think we bring is that [the Navy is] going to go from contract to actually starting to turn out students much quicker than any other competitors,” a Textron executive told Breaking Defense.