Hypersonic missile defense will be crucial in future warfare, according to CSIS. (CSIS graphic)

Updated Feb. 7 at 12:00 pm to include remarks by the head of DoD’s Joint Hypersonics Transition Office.

WASHINGTON: As the Defense Department looks for ways to up its hypersonics game, it needs to refocus its priorities towards protecting ships, air bases and other critical tactical assets from Chinese and Russian cruise missiles and glide vehicles, asserts a new report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“Notwithstanding all the hyperbole, hypersonic missiles are not unstoppable,” Tom Karako, coauthor along with Masao Dahlgren of the study “Complex Air Defense: Countering the Hypersonic Missile Threat,” told Breaking Defense.

“The single most important capability here will be space sensors to track these threats, followed by a glide phase interceptor and a command and control function that can contend with a geographically broad, temporally compressed decision-space,” Karako said. “Hypersonic gliders, for instance, are sometimes described as targeting the gaps and seams of our sensors or interceptors, but they also target the gaps and seams of our command and control structure.”

The report comes just days after the Department of Defense arranged a high-level meeting between senior Pentagon officials, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, and the CEOs of major defense contracting firms — the latest signal of the urgency with which the US is pursuing hypersonic capabilities.

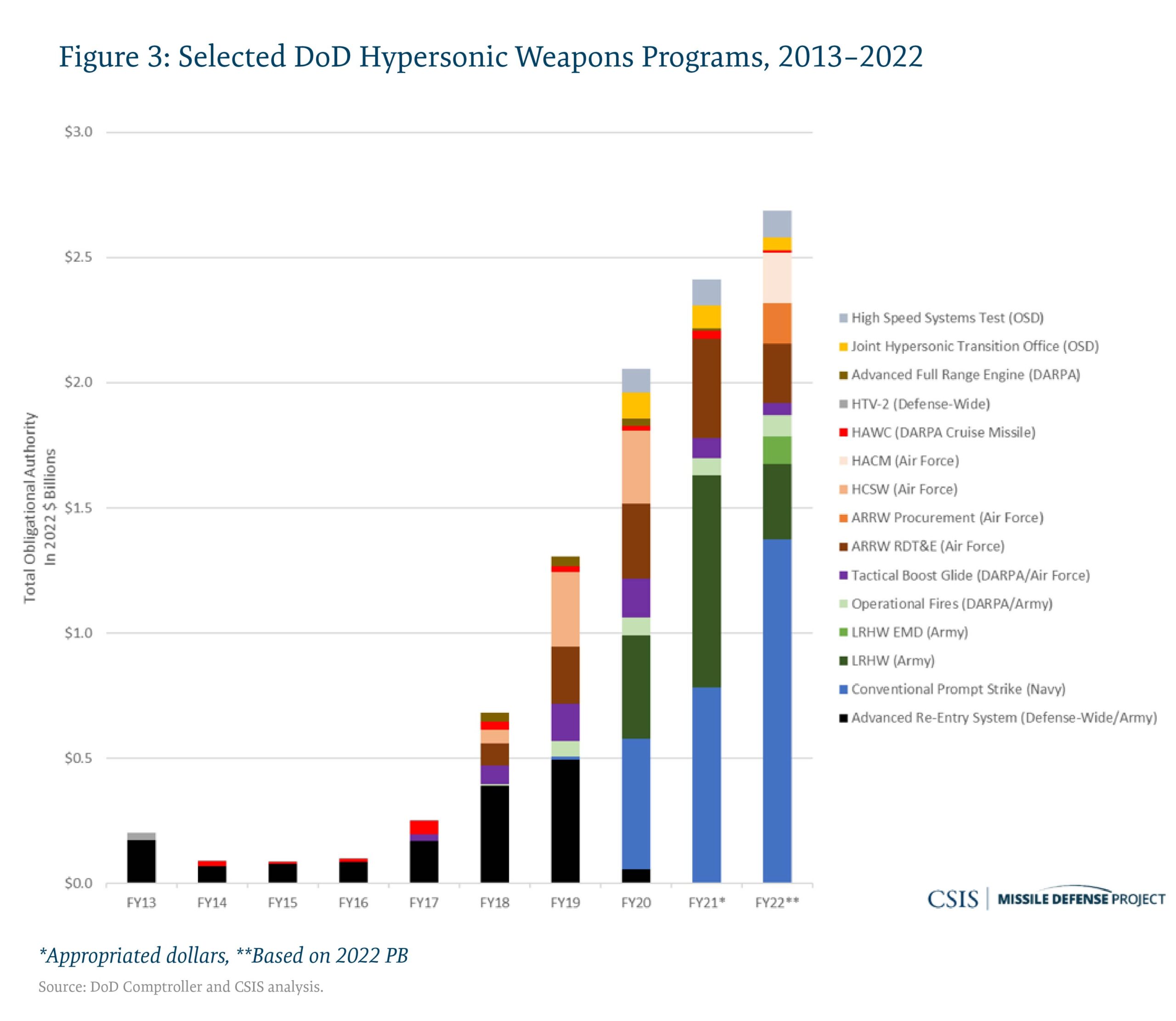

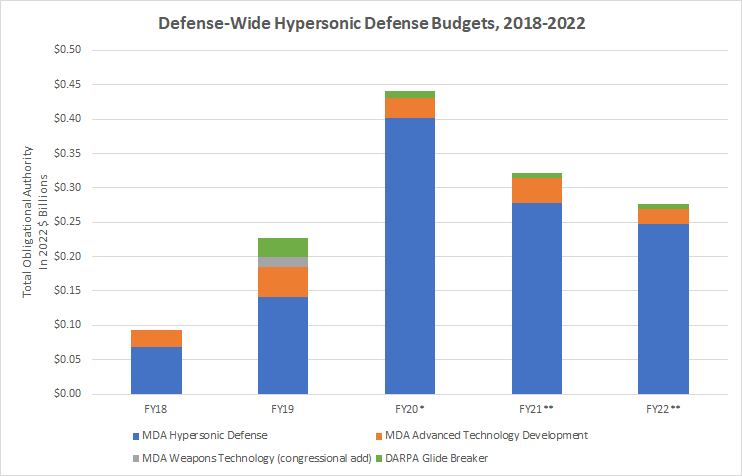

But the CSIS study finds that there is a ginormous disparity between Defense Department spending on offensive hypersonic missile programs and ways to defend against them. Whereas DoD and the services splashed out more than $2.5 billion for offensive hypersonic missile programs in their fiscal 2022 budget requests, CSIS analysis shows that funds budgeted for the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) and DARPA on defensive capabilities barely topped $2.5 million.

Mark Lewis, former acting deputy undersecretary of DoD’s Office of Research & Engineering and an expert on hypersonic tech, agreed with CSIS’s assessment.

“There’s much more emphasis right now on offense than defense,” he told Breaking Defense ahead of the report’s release.

Gillian Bussey, director of the Pentagon’s Joint Hypersonics Transition Office, explained during a CSIS roundtable today that DoD’s focus on developing its own hypersonic weapons makes sense.

“As a department, we’ve chosen to focus on offense first, because a good offense is the best defense and offense is a lot easier,” she said.

At the same time, Lewis, who currently heads the National Defense Industrial Association’s Emerging Technology Institute, cautioned that it is hard to precisely quantify how much is being spent at DoD on each basket.

CSIS chart 2022 on hypersonic defense spending. (CSIS)

This is in part, he explained, because defensive efforts at MDA and the Space Development Agency (SDA) are entangled with other missile defense activities.

Indeed, there are a number of long-standing policy issues with regard to how MDA, SDA and the services will share responsibility for hypersonic missile defense that remain unresolved — leading to both overlaps and cracks in development efforts.

For example, there is a long simmering feud between the Air Force and the Army about defense of air bases around the world, which as the CSIS study notes are likely to become targets of tactical hypersonic missiles. There also has been a kerfuffle between SDA and MDA, which has drawn the ire of Congress, over responsibility for building new sensors to track highly maneuverable hypersonic missiles under the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) effort.

Further, Lewis explained, there is some technology “bleed” between offensive and defensive capabilities — something that Karako also pointed out. “Some of the same characteristics that make hypersonic weapons attractive may hold the key to new approaches to defense design,” Karako said.

And finally, a lot of what is going on in the defensive arena is highly classified. “Not seeing something doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t happening,” Lewis said.

The CSIS study stresses that “hypersonic technology” isn’t a “thing.” Rather it is an attribute — super high speed — that leads to a number of different types of weapon delivery systems that stress US defense and response capabilities. For this reason (as the study’s name suggests), defending against such delivery systems “might be better framed or understood as a complex form of air defense, rather than, say, as an adjunct to ballistic missile defense,” Karako said.

This will necessitate a change in Pentagon thinking about how to approach its strategies and investments.

For Lewis, a key takeaway from the CSIS study is that DoD and the services need to keep their eyes fixed on the issue of protecting against the tactical uses of scram-jet based hypersonic missiles and maneuvering glide vehicles.

“You really need to worry about the tactical things. You really need to defend your surface ships, air bases, all that stuff,” Lewis said.

The CSIS study explains that: “As a practical matter, access to strategic theaters requires effective hypersonic defenses. […] The United States does not compete with unlimited resources. It is not possible to actively defend every critical asset or even broad areas that hypersonic missiles might target. This simple reality requires policy and strategy expectations aligned to preferential defense and a more limited defended asset list.”

Lewis foot-stomped this, saying it is critical that DoD leaders “don’t get distracted” by sensational things, like China’s experimental fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) that may or may not be nuclear capable.

“I don’t want to dismiss what the Russians and Chinese are doing,” he hastened to say. But the real point of the Chinese FOBS was the messaging, not necessarily the capability. “It’s trying to say: We’re now a world power. We want to be able to shoot anything around the world, and we’re not constrained to our backyard,” he said.

Bussey concurred.

“For some reason, ballistic missile threats always seem to get more attention than cruise missile threats,” she told the CSIS panel. “And I had a manager who said: ‘You know, advanced conventional weapons are weapons of actual destruction, as they are actually used. And yet, for some reason, we always seem to pay way more attention to the glide vehicles.”

Boeing buys GKN factory, ending dispute over F-15, F/A-18 parts

Through the deal, Boeing’s litigation with supplier GKN Aerospace will be dropped, and the aerospace giant will take possession of a St. Louis-area factory it used to own.