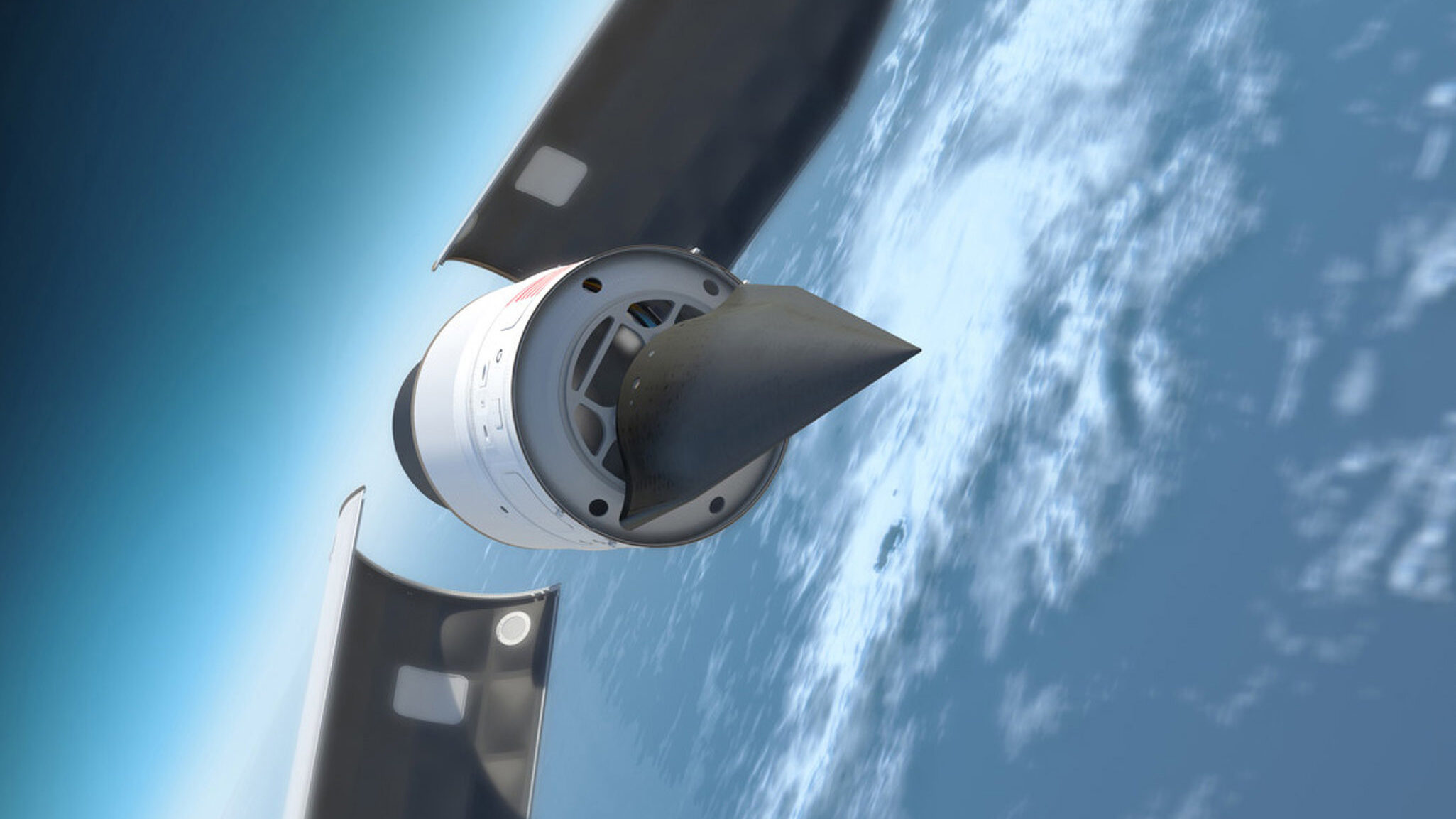

This illustration depicts the Defense Advanced Research Products Agency’s (DARPA) Falcon Hypersonic Test Vehicle as it emerges from its rocket nose cone and prepares to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. DARPA has conducted two test flights of the vehicle; in the second, in 2011, the HTV reached a speed of Mach 20 before losing control. (Image courtesy of DARPA)

When John Hyten was on his way out as vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he lamented that the US had lost its appetite for failure, and as a consequence would find itself trailing in high-risk tech — such as, specifically, hypersonics. In the op ed below, Tate Nurkin of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments echoes Hyten’s warnings and urges the US to embrace not recklessness, but certainly risk if its wants to catch up to geopolitical rivals.

Last week, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks met with CEOs from more than a dozen of America’s defense contractors involved in US hypersonic weapons programs to reinforce the urgency of fielding these systems. According to a Pentagon spokesman, those attending discussed a need to “adopt a ‘test often, fail fast, and learn’ approach which will accelerate the fielding of hypersonic and counter-hypersonic systems.”

This is welcome and timely guidance. Hypersonic weapons are a critical capability for deterring and defeating potential adversaries in the 21st century, and ones the US must develop with superspeed of its own.

Beyond the immediate need for critical investments in hypersonic infrastructure, such as testing ranges, the US must ignore calls to “slow down” in the wake of failed tests, and instead take on even more risk – and more failure – if it doesn’t want to be left behind.

RELATED: At Pentagon meeting on hypersonics, CEOs urge stable funding, better infrastructure

Hypersonic strike systems—both hypersonic glide vehicles (HGV) and air-launched hypersonic missiles—are among the DoD’s most important technology and capability priorities. The 2022 NDAA includes $3.8 billion for hypersonic weapons, up from $3.2 billion in 2021. There are at least six active weapons development programs and dozens of other affiliated research and development efforts across the department.

Some critics of DoD’s hypersonics push have questioned if there is a role for hypersonic systems, arguing that any benefit they provide will be simultaneously incremental and expensive. But the utility of hypersonic strike systems in deterring and fighting modern conflicts is layered and evident.

Hypersonic weapons are not invincible. However, their combination of attributes—extremely fast, ability to strike at long ranges, difficulty to detect and track by current air and missile defense systems, maneuverability—are especially salient in an environment in which increased speed, range, lethality, and precision are necessary for holding at risk time-sensitive targets and degrading or defeating high-end A2/AD and air defense systems.

RELATED: Pentagon needs to prioritize hypersonic defense, not offense, CSIS study says

China and Russia have fielded three HGV systems, and both are pursuing research and development of air-launched weapons. The aggressiveness of China and Russia’s hypersonic development and their success in fielding early iterations of the technology creates what Mike White, DoD’s principal director for hypersonics, calls a worrying “timescale imbalance” in tactical environments. Potential adversaries will be able to strike targets at range within minutes while US weapons will take tens of minutes or longer to travel the same ranges.

This may be even more worrying considering the belief within DoD and the US government that China and Russia’s HGVs could be armed with nuclear warheads It’s an imbalance that can only be addressed by the American pursuit of hypersonic technology to level the strategic playing field. It also places added emphasis on the need to accelerate the progress of hypersonic defense.

The Pentagon should not feel compelled to match everything China and Russia do. Some of these fielded systems may not have been sufficiently tested across a range of operational conditions and scenarios. More importantly, the US should be strategic and reflective—rather than just reflexive—in the technologies it develops and how it employs them.

And it is not just Russia and China. North Korea’s recently claimed, although dubiously, to have tested a hypersonic weapon. US allies and partners including Japan, France, South Korea, Australia (in conjunction with the US) and India all have active programs as well, reinforcing the prominent role these weapons will play in deterring and, if necessary, defeating emerging threats.

Critiques of America’s hypersonic weapons programs have also frequently and forcefully centered on the pace and success rate of DoD’s hypersonic testing. It is true that the handful of flight tests that have taken place in 2020 and 2021 are not enough.

As former Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Michael Griffin noted last year, “We need to be doing one test a week and not one test a quarter.” Any bureaucratic challenges slowing testing are compounded by a lack of sufficient availability of testing ranges, according to a recent internal DoD report obtained by Bloomberg News.

It is also true that several tests have failed, which notionally is not necessarily a poor outcome. As a Pentagon statement following an October 2021 failed test pointed out, “experiments and tests both successful and unsuccessful are the backbone of developing highly complex and critical technologies at tremendous speed, as the department is doing with hypersonic technologies.”

However, nearly all these failures have been due to problems unrelated to the hypersonic technologies, meaning that the hypersonic technology was not deployed and lessons about it were not yet learned.

To focus exclusively on these failures and call for a more deliberate approach to hypersonic development, though, is to ignore or discount the progress DoD has made and the successful tests that have occurred, as well as the DoD’s increasing use of high-performance computing modeling and simulation capabilities in conjunction with testing.

Some recent examples: In October, Sandia National Laboratory launched three sounding rockets on-board of which tests of 23 sub-systems were successfully run. A month earlier, DARPA completed a successful free-flight test of its Hypersonic Air Breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC). There have also been three successful tests of Lockheed Martin’s solid-state engine for the Navy’s Intermediate Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IR-CPS) program in the past year. In fact, in January the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Michael Gilday assessed that the IR-CPS program “has actually met or exceeded every benchmark and milestone over the last couple of years.”

Building on these successes and other developments across the Pentagon’s extensive hypersonic portfolio will require a more aggressive approach to testing and experimentation, including investing now in test range capacity, both in the U.S. and with key allies such as Australia.

More fundamentally, achieving DoD’s admittedly ambitious objectives for testing and fielding defenses against hypersonic weapons will require a heightened tolerance of risk. This does not mean embracing carelessness or recklessness. It does mean infusing urgency with a broad perspective on hypersonic development, learning as much as possible from each opportunity, and not being deterred from achieving long-term success by episodic short-term setbacks.

Tate Nurkin is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and Forward Defense at the Atlantic Council.

Army wraps up FLRAA PDR, incorporating special ops design changes

According to a SOCOM official, the Army included feedback from the command that led to design changes like hardware for a refueling probe and features that will enable special operators to make unique modifications.