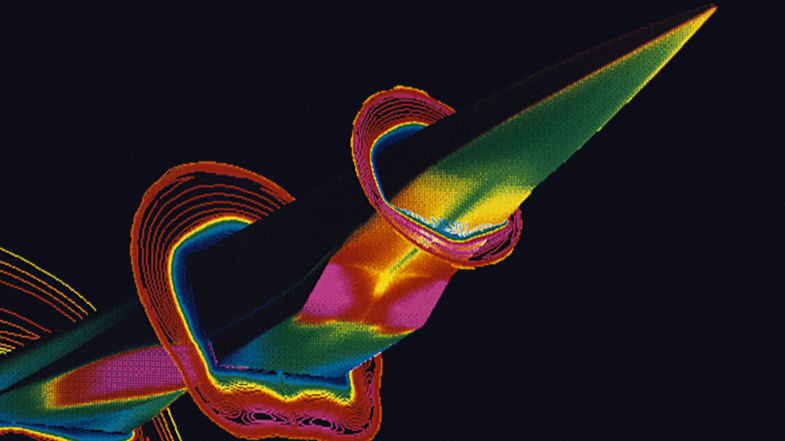

Hypersonic missile defense raises key questions for lawmakers on investment, the Congressional Research Service says. (Graphic by the Center for Strategic and International Studies)

WASHINGTON: The bottom-line question for Congress about Pentagon plans for hypersonic missile defense is whether the approximately $250 million being spent by the Pentagon to develop systems — a sum that potentially could balloon into the billions over time — is warranted by either the threat or the current status of US technologies to counter them, according to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service.

“Is an acceleration of research on hypersonic missile defense options both necessary and technologically feasible? Does the technological maturity of hypersonic missile defense options warrant current funding levels?” the CRS report, “Hypersonic Missile Defense: Issues for Congress” asks.

In particular, the report from the independent congressional think tank points to concerns about the capability of current military command and control (C2) networks and decision-making processes to ensure fast enough response — a problem that is supposed to be addressed by the Defense Department’s Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) strategy that, as of today, remains to be substantiated.

The brief report [PDF], published in late January, does not attempt to answer those question or others it identified, but it could frame lawmakers’ inquiries of top military officials next time they appear for hearings about plans to counter to hypersonic threats.

Targeting What Threats?

Over the past year or so, there has been a growing debate within the Defense Department about the balance between spending on defense against adversary hypersonic missiles and offensive hypersonic weapons being developed by the US military services.

Key congressional and US military leaders have been increasingly apoplectic about Russian and especially Chinese progress in developing long-range hypersonic missiles — including those that could possibly carry nuclear weapons.

The CRS report notes that Russia “reportedly fielded its first hypersonic weapons in December 2019, while some experts believe that China fielded hypersonic weapons as early as 2020.” The US isn’t expected to field its own hypersonic weapon until next year, despite some $2.5 billion in current investment in offensive systems by the various military services.

Victoria Samson of Secure World Foundation and a long-time missile defense analyst suggested that in the race to catch up, the US isn’t fully considering how it’s running the race.

“I get the sense that a lot of what is driving US interest in it is that China and Russia are working on their own program,” Samson told Breaking Defense. “Of course what peer adversaries are investing in should be a consideration for US officials, but it should not be the sole driver, and the United States does not need to do a one-for-one type of investment strategy.”

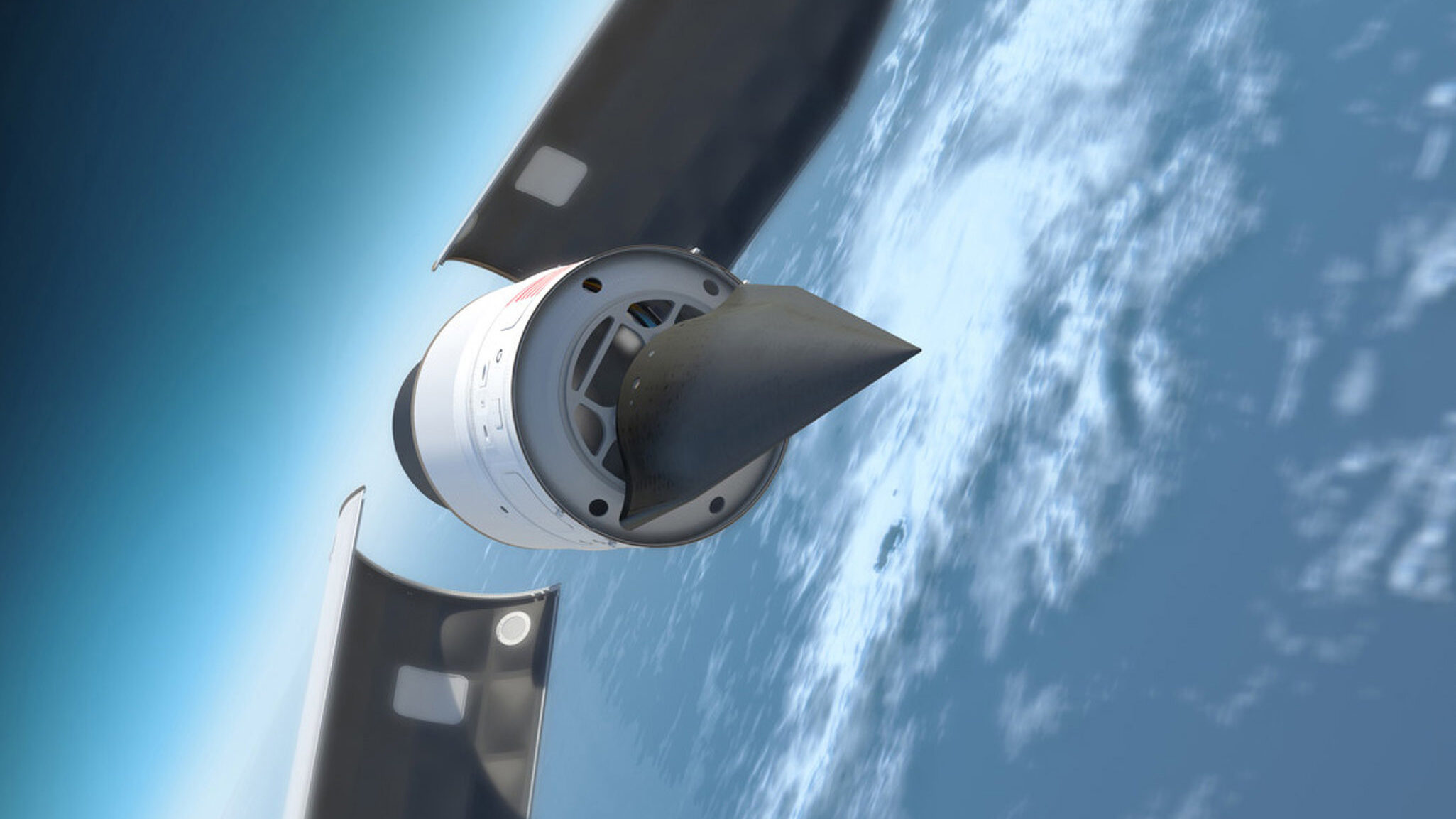

This illustration depicts the Defense Advanced Research Products Agency’s (DARPA) Falcon Hypersonic Test Vehicle as it emerges from its rocket nose cone and prepares to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. DARPA has conducted two test flights of the vehicle; in the second, in 2011, the HTV reached a speed of Mach 20 before losing control. (Image courtesy of DARPA)

The skepticism isn’t just outside government. In September Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said he wasn’t “satisfied with the degree to which we have figured out what we need for hypersonics — of what type, for what missions.”

There are additional complications in decision-making due to the fact that hypersonic missiles can be configured to carry both nuclear and conventional missiles — including the ever-thorny political issues around nuclear deterrence. This makes it somewhat difficult to determine where exactly investments should be made.

Though the CRS report notes the fiscal 2020 defense authorization act compels the Missile Defense Agency to “develop a hypersonic and ballistic missile tracking space sensor payload,” that agency is actually bound by law to constrain its targeting capabilities to only nuclear threats from rogue states North Korea and Iran. Thus, if the rationale for increased spending on new hypersonic missile defense systems is to counter their not-so-impressive capabilities, rather than those of Russia or China, then that raises issues around whether such programs as MDA’s Glide Phase Interceptor are warranted.

On the other hand, if, as others argue, the real threats are from conventional Chinese and Russian hypersonic missiles that can be used against tactical assets like ships at sea and overseas bases, then perhaps instead investment by the military services in non-strategic defenses and offensive hypersonic missiles of their own are more important. But those efforts also face a number of unanswered questions.

For example, it is unclear that DoD has a strategy, plan and/or capabilities to coordinate salvos of long-range strike weapons, including offensive hypersonic missiles, being developed by the various military services to target Chinese and Russian launch facilities as part of their plans for future all-domain operations. Those development programs already have piqued inter-service rivalry.

Command And Control: A Missing Linchpin

Another pointed question from the new report: “Does DOD have the enabling capabilities, such as adequate command and control architectures, needed to execute hypersonic missile defense?”

Lawmakers should be quizzing Pentagon leaders, the report suggests, about whether DoD’s multiple and stovepiped missile defense C2 systems used by MDA, the military services and the battlefield commanders at the various combatant commands can process data quickly enough allow timely response.

CRS’s analysis quoted from a 2019 issue brief from the American Foreign Policy Council.

That brief stated [PDF]:

“The development of complete countermeasures to offset the hypersonic threat will likely require not only detection capabilities, but also a hybrid approach of kinetic interceptors and other non-kinetic means as well as an entire new command and control architecture capable of processing data quickly enough to respond to and neutralize an incoming hypersonic threat – a far cry from the current reality.”

This problem also was flagged by the Missile Defense Project of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in its February study, “Complex Air Defense: Countering the Hypersonic Missile Threat.”

CSIS found that the speed and data ingestion capacity of current computer processing systems underpinning current C2 networks are already unable to handle the vast amounts of data coming in from various sensor platforms, nor can they adequately share that information in time for commanders to make decisions.

“The speed of hypersonic weapons leaves little time for computing a fire control solution, communicating with command authorities, and completing an engagement,” the CSIS reported explained. However, the study found that current computer systems simply can’t handle the job.

“Presently, various combatant commands cannot process the substantial majority of collected radar, flight test, or shared intelligence data—challenges that motivated the Department of Defense’s Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) program,” the report said.

There also is a need for software-based decision-making tools powered by artificial intelligence and machine learning to assist commanders in visualization of the threats in near-real time and speed decision-making about responses, CSIS noted — tools for which combatant commanders, led by Northern Command head Gen. Glen VanHerck, already are clamoring.

While MDA is working on to modernize its own Command and Control, Battle Management and Communications (C2BMC) network, senior MDA officials also have been clear that JADC2 will be critical to hypersonic missile defense.

But so far, not so much progress has been made in developing and implementing the kind of modern data-sharing standards and platforms foundational to JADC2. Part of that problem is reluctance by the individual services to move away from their own bespoke (and expensive) C2 networks.