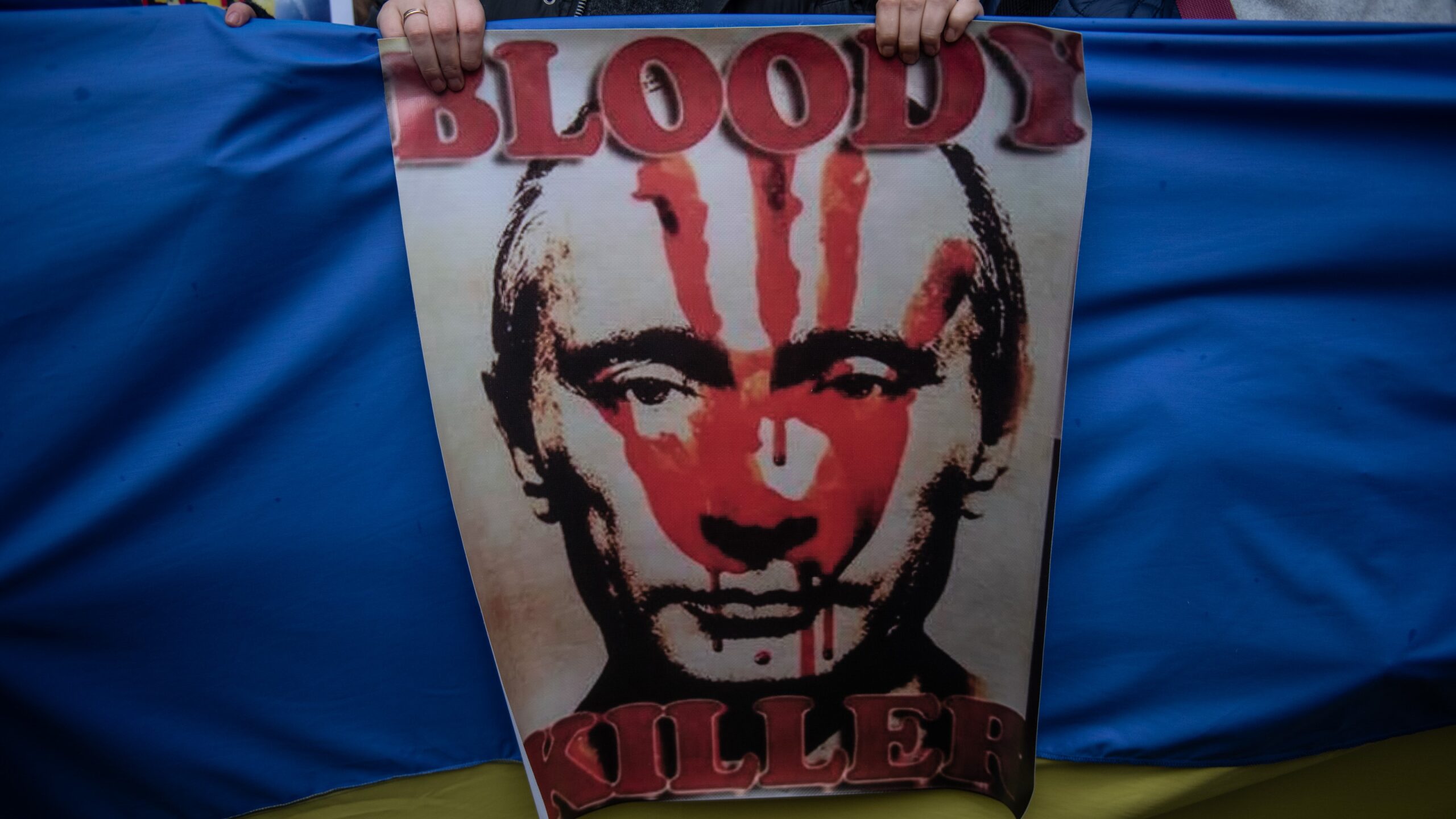

A poster depicting Russian President Vladimir Putin is seen as Ukranians gather in protest outside the Russian Consulate on February 25, 2022 in Istanbul, Turkey. (Burak Kara/Getty Images)

This is the latest in a series of regular columns by Robbin Laird, where he will tackle current defense issues through the lens of more than 45 years of defense expertise in both the US and abroad. The goal of these columns: to look back at how questions and perspectives of the past should inform decisions being made today.

No one could accuse President Ronald Reagan on being soft on the Russians. Yet over the course of his presidency, at one of the tensest points of the Cold War, he learned to tone down his rhetoric about Russia in order to not trigger nuclear war. It’s something the Biden administration should keep in mind: messaging designed for domestic consumption has a global impact as well, and being tone deaf to what your adversary is hearing can only turn out badly.

Recent commentary from the Biden administration brings back memories of the bad old days. First, there was President Joe Biden’s comments in late March that Russian strongman Vladimir Putin “cannot remain in power” following the invasion of Ukraine. Although the White House quickly walked back the idea that Biden was calling for regime change in Moscow, the statement dominated several days of news coverage. More recently, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said the US wants a “weakened” Russia at the end of the Ukraine conflict.

You can be sure those comments are setting off big alarms inside the Kremlin, at a time when Russia’s failures in Ukraine are already raising concerns that Putin could resort to the use of nuclear weapons, tactical or otherwise, to try and regain an advantage in Europe. And we have historical reason to believe that the message Putin will take away from all this is to prepare for the worst-case scenario.

The initial Reagan administration was staffed by a wide range of hard-liners and anti-communists whose rhetoric, in my view, had a longer reach than their sense of policy realism. Reagan quickly built a reputation of tough talk towards Moscow. This was especially true before George Schultz, one of the great statesmen of the 20th century, joined the administration in mid-1982.

The unfortunate side of this was the head of the Soviet Union, Yuri Andropov, was interpreting this rhetoric as Reagan legitimizing nuclear war against the Soviet Union. This isn’t speculation: thanks to two unique spy channels, which would later be known as the Gordievsky affair in the UK case and the Farewell affair in the French case, Andropov’s thinking is well documented. We also know that thinking was communicated through both Reagan’s closest political ally abroad, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and French president François Mitterrand — the latter someone whom the Reagan administration had little time for due to the inclusion of communists in his cabinet.

I have written in some detail about these two cases in my co-authored book with Murielle Delaporte entitled “The Return of Direct Defense in Europe: Meeting the Challenge of 21st Century Authoritarian Powers.” As we concluded about the two spy inputs: “These two key spy stories of the 1980s could have the impact they would have on Western policy only if there was an ability of Western governments to work together effectively and to have a unity of will to deal with the Soviet threat. President Reagan shaped an Administration which could find ways to work with Western allies, even those whose politics and worldviews were quite different from his.”

RELATED: Two pathways to recovering Russia expertise in the US military

The problem is that the lines of communication, as I have written previously, are actually more frayed now than during the 1983 near-nuclear-crisis. Which means that it’s more important than ever that 1) the White House watch its rhetoric, and 2) that allies and partners can act as go-betweens.

In addition to the blunt inputs which both Thatcher and Mitterrand provided to Reagan, there was a network of Russian and Warsaw Pact officers who interacted with American and allied military and intelligence officers who had a very significant impact on getting their higher ups to understand how out of control the exchanges between Reagan and Andropov were becoming. If readers want greater insight into these issues, I highly recommend my colleague Brian Morra’s new novel “The Able Archers,” which provides significant insight into how military and intelligence officers on the US and allied side worked with their counterparts on the Soviet side to shape understanding for their senior leaders of how close we were coming to nuclear war.

And to be clear, shaping Western unity in the face of nuclear threats is never a given. The Euromissile crisis in Europe in the early 1980s was deeply divisive and there is little doubt that today, the presence of a nuclear threat unity lasts as long as you are not the target of a nuclear threat.

We avoided nuclear war in 1983 due to the President learning from his allies and his administration listening to experienced military and intelligence officers. Let us hope we are as fortunate this time around in the Ukrainian crisis.

Northrop sees F-16 IVEWS, IBCS as ‘multibillion dollar’ international sales drivers

In addition, CEO Kathy Warden says the company sees a chance to sell up to five Triton UAVs to the NATO alliance.