Gen. Chance Saltzman (right) assumes command of the Space Force during a transition ceremony for the Chief of Space Operations at Joint Base Andrews, Md., Nov. 2, 2022. Gen. Chance Saltzman relieved Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond (center) as the second CSO, the senior uniformed officer heading the Space Force. (US Air Force photo by Wayne A. Clark)

WASHINGTON — In early January during a virtual Mitchell Institute event, the Space Force’s first chief of space operations promised that the coming year would see the service take real-world steps towards a new on-orbit posture that would be better shaped to withstand adversary attack.

“We have got to shift the space architecture, if you will, from a handful of exquisite capabilities that are very hard to defend to a more robust, more resilient architecture by design. That’s what this force design work is doing,” Gen. Jay Raymond said. “And so we will begin our pivot significantly to a resilient architecture this next year.”

[This article is one of many in a series in which Breaking Defense reporters look back on the most significant (and entertaining) news stories of 2022 and look forward to what 2023 may hold.]

In March, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, who is the Defense Department civilian directly overseeing the Space Force as well as the Air Force, foot-stomped the need for a more survivable satellite architecture — making “defining a resilient and effective space order of battle” one of his seven “imperatives” for the future.

As 2022 wraps up, Raymond has retired and turned over the Space Force’s reins to Gen. Chance Saltzman, but it is clear that the service is headed, albeit slowly and ponderously, into the “pivot” he promised. Space Force leaders have taken a number of baby steps this year towards dispersing satellites into multiple orbits, making it harder for an adversary to wipe them all out. The service also has made some progress towards figuring out how to better use commercial satellites to augment the military’s own constellations.

That said, the long pole in the tent remains the thorny problem of reforming space acquisition. There have been some positive signals on that front, largely emanating from a number of organizational restructures — especially the appointment in May of Frank Calvelli to serve as the first-ever assistant secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration, and the top space acquisition executive. On the other hand, we’ve yet to see a lot of fruit from those seeds of change.

SDA Tracking Layer optimized to keep tabs on low-flying, maneuvering hypersonic missiles. (SDA graphic)

Missile Warning: From Few To Many

The Space Force put money down in 2022 towards revamping how it does missile warning/tracking by launching numerous smaller satellites into lower orbits rather than relying on a handful of very large birds in geosynchronous orbit some 36,000 kilometers above the Earth — the latter of which former Vice Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. John Hyten famously called “fat juicy targets.”

In its fiscal 2023 budget request, the service asked for some $828 million from FY23 through FY27 for a new program called “Resilient Missile Warning Missile Tracking – Medium Earth Orbit (MEO),” with the hopes of orbiting at least four satellites to provide an “initial warfighting capability” by 2028. This new effort, led by Space Systems Command (SSC), will be complementary to the Space Development Agency’s program to put a constellation of some 100 Tracking Layer satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) with a primary mission of better keeping tabs on low hypersonic missiles that present challenges for current infrared monitoring satellites.

And in September, SDA Director Derek Tournear confirmed that those two constellations would eventually replace the Defense Department’s current Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) satellites in GEO and their already planned successors, the Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR) satellites budgeted at a whopping $12 billion between FY23 and FY27.

“We’ll do away with the GEOs, and the big, exquisite expensive satellites,” Tournear said.

‘Hybrid Architecture’ Includes Commercial

“Hybrid architecture” is latest buzz word for the changing shape of the Space Force’s satellite network structure, which will not only see satellites dispersed across various orbits but also involve greater reliance on commercial constellations. The Ukraine war in particular has pumped up interest within the national security community about the value of commercial satellite services, especially communications and remote sensing.

The Space Warfighting Analysis Center incorporated the hybrid concept into its space data transport force design. And DoD’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and SDA this year took the first tiny steps toward implementing that design.

Further, SSC in March announced the creation of the Commercial Services Office, designed to serve as a one-stop-shop for connecting commercial space operators — from communications to remote sensing to space monitoring firms — to potential government customers. The new office is looking both to widen DoD’s use of commercial capabilities and to shift the way the Space Force contracts for them. The goal is to move toward a “managed service” model that mimics how most customers contract for telephone and internet connectivity. The Army, for example, has been working with the Space Force to pilot using the managed service concept to buy SATCOM.

Acquisition, Acquisition, Acquisition

For Kendall, the need for speedier acquisition and fielding of new tech is all about keeping ahead of “China, China, China.” But the ability to do that in the space domain requires big changes in the processes used by the Space Force to plan and buy capabilities.

Calvelli seems to be off to a fast start on attempting to do that. First, he gave SDA a soft landing in its new home within the Space Force, making no “dramatic organizational changes.” More importantly, he also made it clear he intends to steer the bigger Space Force acquisition portfolio, worth some $72 billion, managed by SSC in the direction of SDA’s two-year, iterative development-to-launch model.

In November, Calvelli also put forward guidelines to his workforce in the form of nine “tenets,” including building smaller satellites and ground systems, avoiding over-classification of programs, eschewing cost-plus contracts and holding industry feet to the fire in performing to contract specifications.

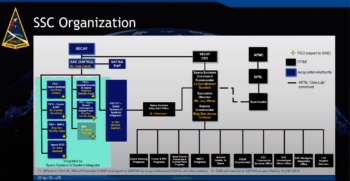

Space Systems Command organization chart. (SSC briefing slide)

SSC’s new(ish) leader, Lt. Gen. Michael Guetlein, also took steps back in March designed to speed acquisition.

Guetlein stamped his reform plans with the motto: “exploit what we have, buy what we can, and build only what we must.” This means finding new ways to integrate current space capabilities into operations across DoD, and looking more assiduously at opportunities to buy commercial and allied capabilities before deciding to start a new program to build a bespoke system.

As of the end of 2022, however, most of these changes are in the embryonic stages — and some plans already are experiencing delays, such as SDA’s launch of its first batch of satellites that has slipped from September 2022 to March 2023. The devil will, as always, be in the details of how plans are implemented, budgeted and contracted. Still, as another old saying goes, a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.