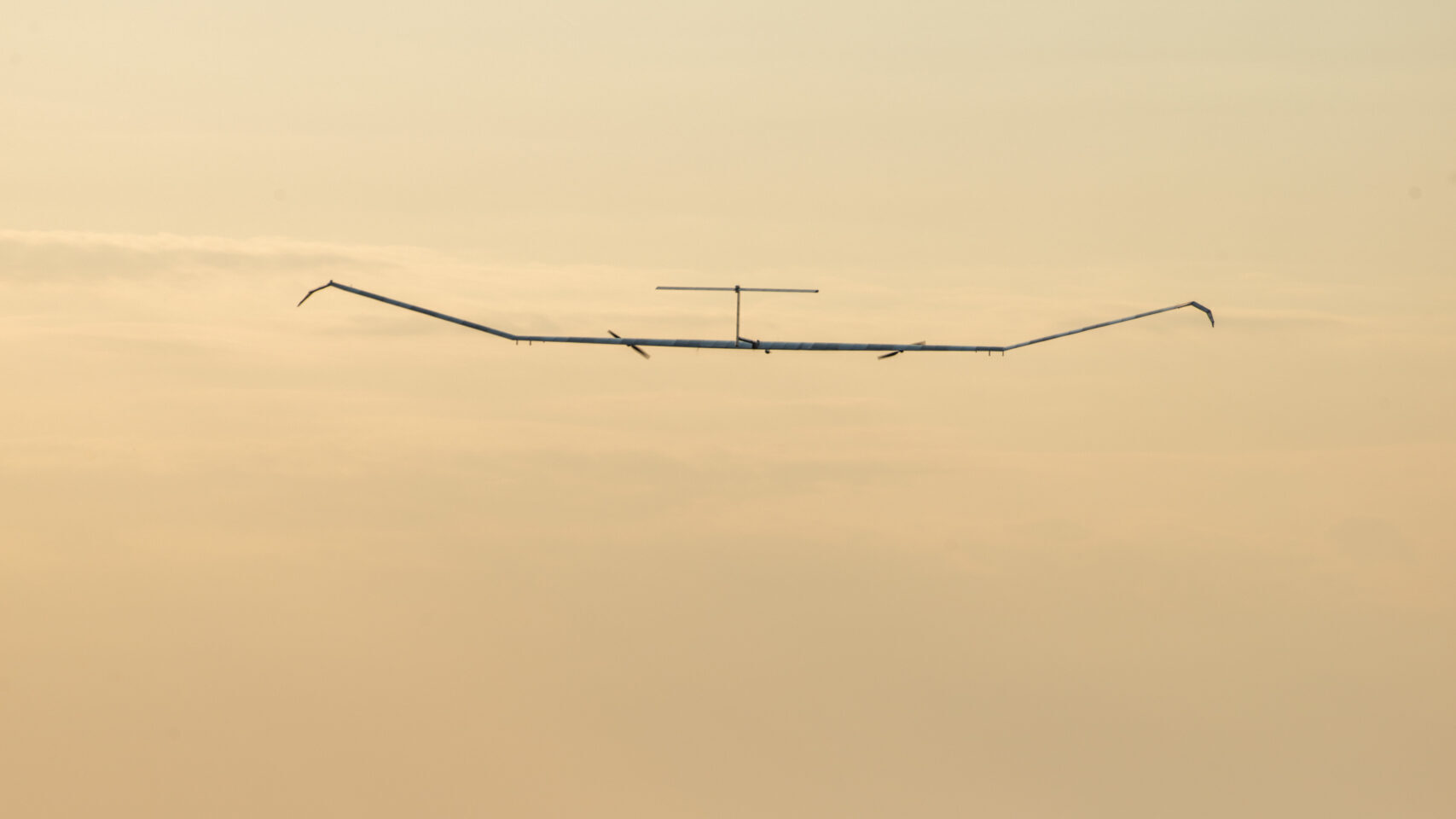

The Airbus Zephyr stayed aloft for 68 days in 2022. (DVIDS)

PARIS — With both the air and space domains becoming more crowded than ever, French military planners are preparing a deep dive into whether they can take advantage of a largely ignored region known as “higher airspace” — the unregulated area above where conventional air traffic operates.

This space, loosely set at between 20-100 km above sea-level, is too high for aircraft to operate in, too low for satellites to orbit in. But increasingly, new technology with balloons, solar-powered “wings” and drones are starting to make timid incursions in this region, leading the French Armed Forces chief of staff, Gen. Thierry Burkhard, to task the Air and Space Force to come up with a report by this summer about how to use and protect this space.

Work has already begun inside the French military, but officials used a Jan. 9 seminar at the École Militaire (war college) in Paris to make the work public. Gen. Stéphane Mille, the chief of staff of the Air and Space Force, told media in an informal meeting after the seminar that the event “took the brakes off our studies on higher airspace operations,” or HAO. “Today we are launching our thinking on this and will probably develop a concept which might later lead to a doctrine.”

Mille said there has been no official Expression of Needs issued by the Ministry of the Armed Forces for HAO capabilities, “but we need to look at what industry is doing and ask ourselves what we want to do.”

RELATED: Macron: France’s new strategic review to meet ‘dangerous moment’ in the world

To clarify the space being discussed: the Earth’s atmosphere is divided into four layers. The closest to the surface of the Earth is the troposphere, starting at sea-level and rising to about 12 km. The stratosphere is the layer above, rising to about 50 km; this is where aircraft fly when travelling eastwards to take advantage of the jet stream. Then there is the mesosphere, which rises to about 85-100 km. It’s the coldest layer at around -100° Celsius, and protects Earth from large meteoroids that burn up from the friction they encounter in this layer. Finally the thermosphere (itself divided into the ionosphere and the exosphere) which is where the international space station sits. That’s the thickest layer, where UV radiation from the sun heats the air to upwards of 1,500° Celsius.

HAO starts about midway up the stratosphere, at around 20km, and goes up to the top of the mesosphere, at around 100 km. This “unexploited” zone could not be used until about a decade ago, Mille said, “because engines couldn’t function in this layer of altitude.

“But today technology allows sensor-carrying balloons, for example, to use this space. Do we really want a balloon sent up by a hostile force sitting above Paris and watching our every move and be unable to deal with it?”

Gen. Frédéric Parisot, the deputy chief of staff of the French Air and Space Force, said the resulting roadmap would enable the Air Force to establish the types of operations likely to occur in this zone and the means necessary to achieve them. “We cannot be absent from this layer of altitude. We need to be present in all three domains: air, HAO and space.”

Some 20 countries are looking into HAO, according to Frank Lefevre, director of defense programs at the ONERA, the national laboratory of aerospace research. And, Mille told Breaking Defense, the question of HAO is a subject “which we do talk about occasionally with other European Air Forces.”

Industry Weighs In

Industry is ahead of the game working on different technologies from balloons to wings, with execs from three major European firms laying out their ideas during the seminar.

Thales Alenia Space is working on a HAO balloon, the Stratobus. CEO Hervé Derrey explained at the event that “a stratospheric balloon like this can carry 250 kg (552 pounds) of sensors much closer to the Earth than a satellite, at about 19 km altitude, and be set to stay above a given spot to observe it for up to one year.” A 120-meter (394 feet) long demonstrator is scheduled to fly in 2025 in collaboration with Spain from Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands.

Dassault Aviation is working on a prototype aircraft that would operate in this gap. Marc Valès, president of space programs at the company, remarked that “hydrogen-powered space aircraft can fly much faster, are reusable, flexible and reliable.” Dassault has been working on Space Rider, the operational version of the Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle (IXV) demonstrator, which flew on February 11, 2015. Space Rider is part of a European Space Agency Program, led by Thales Alenia Space-Italy, to develop a reuseable space transportation system.

Airbus, meanwhile, has developed a huge wing, the Zephyr, which in 2022 flew for 64 continuous days until it crashed in Arizona. Stéphane Vesval, senior vice-president for sales & marketing, space systems at Airbus Defence and Space, said the advantage of this type of wing was the sensors it could carry allowing up to 18cm resolution images being taken of the zones it glides over.

But technology is not the only challenge. Legislation will play a huge part too. For the moment every country is sovereign up to 66,000 feet altitude — the equivalent, if you like, of a country’s maritime exclusive economic zone. And like with maritime law, the space beyond that zone becomes international. Right now, the any higher altitude operations would happen in what is effectively international space, an area largely ungoverned by legal agreements.

Gen. Philippe Morales, commander of air defense and airborne operations, remarked that “the explosion in the numbers of private space operators has completely changed the scene.” Whereas before it was only government organizations that had access to the technologies needed to put vehicles into the three highest levels of atmosphere, private firms now have more capabilities than ever — as do other nations. In essence that means China or Russia could park a balloon at 66,100 feet up and have it hang out over the Pentagon without breaking any rules about airspace.

“This is no longer science fiction,” remarked Lefevre.

“We have to imagine regulations for this quasi-virgin space,” remarked Nathalie Le Cam, project manager space and high altitude operations at the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), adding that a roadmap would be submitted to the European Commission next month. She said she could already reveal three of its principal recommendations: countries will remain sovereign in this space; there should be a joint approach as each country cannot act by itself; and the domain is not well known so it is difficult to establish regulations right away.

That last point is important as France goes about designing its strategy. “We need to coordinate internationally and should not go too far in regulating” cautioned Gen. Stéphane Virem, head of national aeronautical security.

Connecticut lawmakers to grill Army, Lockheed about job cuts at Sikorsky helicopter unit

“The Connecticut delegation has questions about why, with that [FY24] appropriation in hand, this happened,” said Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn.