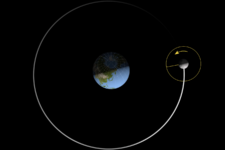

LeoLabs says its radar spotted the release of a sub-satellite, dubbed Object C, by Russia’s Cosmos 2570 satellite on Thanksgiving Day. (LeoLabs handout)

UPDATED 12/13/2023 at 4:41pm ET with comments from Col. Raj Agrawal, commander of the Space Delta 2.

WASHINGTON — Space monitoring startup LeoLabs says it has spotted a trend: Russia in particular, but China too, seem to be timing potentially threatening on-orbit activities to coincide with US holidays — presumably when fewer American skywatchers are actually looking.

“It may be on purpose. It probably is,” Ed Lu, LeoLabs cofounder and chief technology officer, told Breaking Defense.

The latest evidence happened on Nov. 23, US Thanksgiving, when Russia’s Cosmos 2570 satellite in low Earth orbit (LEO) revealed itself to be a Matryoshka (nesting) doll system — comprising three consecutively smaller birds, performing up-close operations around each other, according to the company.

This “spawning” event mimicked the activity of Cosmos 2565, launched on Nov. 30, 2022 and believed to be an electronic reconnaissance satellite, which released a daughter satellite (Cosmos 2566) on Dec. 2, and which, in turn, released its own baby satellite on Dec. 24 (Christmas Eve), according to LeoLabs.

Similarly, on the 25 and 26 of November 2022, LeoLabs said it observed China’s spaceplane, which Beijing calls Test Spacecraft 2, “conduct[ing] rendezvous and proximity operations” that involved a docking maneuver by a satellite it released, Victoria Heath, LeoLabs team lead for communications and marketing, told Breaking Defense. A second docking “likely took place” around Jan. 10, 2023, she said.

While it’s unclear what the child-satellites are up to, sub-satellite deployments “can be a method of deploying co-orbital ASATs [anti-satellite weapons] or covert payloads that may pose a risk to sensitive or classified satellites,” LeoLabs said in an analysis of the Russian operations provided to Breaking Defense.

Owen Marshall, a space domain awareness analyst at LeoLabs, told Breaking Defense that the convenient timing can allow some satellite maneuvers to go undetected for periods of time and thus provide adversaries with a “warfighting advantage.”

“So, the the fact that you can release something, and if you can release it in such a way that that nobody realized you released it, then you essentially have a secret payload up there without its own launch. Until somebody catches up to it, it’s hidden for some periods,” he explained.

With regard to Cosmos 2570, LeoLabs’s analysis said that based on Space Force’s data, the service’s 18th Space Defense Squadron, responsible for space domain awareness, lost track of it when it maneuvered shortly after launch, but that LeoLabs days later was able to find it and its daughter, called Object C.

“We were able to track both objects quickly and send frequent updates. On November 24, we were the first to detect, catalog, and deliver alerts to the Joint Task Force – Space Defense (JCO) on a secondary object released by sub-satellite Object C before the public catalog was able to respond. This prompted urgent action by all parties to track and identify the new object, now called Object D,” said the LeoLabs analysis, provided to Breaking Defense.

“We were able to track both objects quickly, utilizing a cue received from the 18th, and send frequent updates,” LeoLabs added.

JCO stands for the Joint Task Force-Space Defense (JTF-SD) Commercial Operations Cell, which coordinates with private satellite operators and companies offering space tracking services for US Space Command. The JTF-SD is SPACECOM’s functional component command responsible for space domain awareness.

Col. Raj Agrawal, commander of the Space Delta 2, under which the 18th Space Defense Squadron falls, told Breaking Defense that the Delta “tracked Cosmos 2570 starting from launch with consistent updates to the TLEs (two line elements) except for when the satellite maneuvered. … Upon completion of the maneuver, Space Delta 2 quickly re-associated the satellite’s TLE. The time it takes for analysts to publish the re-associated TLE can appear to external agencies as a “delay;” however, there was no loss of custody of Cosmos 2570.” (Two line elements are the basic measurements of an objects position on-orbit.)

Then on Dec. 6, Cosmos 2570’s granddaughter began another maneuver, bringing it within less than 1 kilometer of its mother — extremely close and well beyond what is normally considered safe for orbital operations, Heath said. That move happened in “favorable lighting conditions,” suggesting that the granddaughter “has an electro-optical (EO) sensor payload.”

Lu said that the problem of keeping tabs on sub-satellites and their maneuvers is already outpacing the ability of human analysts to keep up, and is only going to get worse as the pace of launch continues to grow every year. This means that it is imperative for the Pentagon to bring automated systems to sort through the data to bear as soon as possible.

“There are too many satellites, there are too many places to hide. This year, there were more than 3,000 satellites launched. So, that’s 10 new satellites a day. There aren’t that many analysts, right? And next year is going to be another 40 percent larger than that. OK, so, we’re talking 15 satellites a day on average,” he said.

“We have to make that transition to these automated systems for monitoring.”

In the meantime, as the winter holidays approach, US government space-watchers might have a lot more on their plates than tracking Santa.

New Space Force ‘International Partnership Strategy’ coming next year

UK Air Marshal Paul Godfrey told the Center for Strategic and International Studies that his remit includes ensuring that there are clear “touch points” for allies and partners to interact with the nascent Space Force Futures Command.